art

When I was a kid in Caltagirone, Sicily, everybody worked hard all the time - grueling manual labor in the fields and factories. By the time I was eight years old, I was already working with my father in a ceramic-sculpture foundry. I didn't do much more than sweep the floors, but I was around all sorts of craftspeople and began to see that there were some forms of hard work that were more fulfilling than others. So I began to think about becoming a painter. I took my first steps in that direction at 13. By the time I was 18, I'd opened a studio and was painting and sculpting on my own. In those days, the arts community was an exciting place where we shared ideas, fed on each others' energy and competed with each other for good commissions. I'm not ashamed to admit that I thought the established artists I hung out with were cool and powerful in their own ways - and that I wanted to be just like them. Given the specific nature of my art, it's not surprising that the great Italian masters heavily influenced my work right from the start, including Michelangelo, Raphael and especially Leonardo Da Vinci. They are my heroes, and I see the work I do as a modest continuation of the traditions they established. These artists taught me that great art is about passion and the desire to

Sometimes it's the most ordinary experiences that yield the most sublime memories - the pleasant surprise, a beautiful view, the warmth of the sun after a dip in the ocean. For me (and I suspect I'm not alone), these experiences occur

The Crown Fountain in Chicago's Millennium Park is an ingenious fusion of artistic vision and high-tech water effects in which sculptor Juame Plensa' s creative concepts were brought to life by an interdisciplinary team that included the waterfeature designers at Crystal Fountains. Here, Larry O'Hearn describes how the firm met the challenge and helped give Chicago's residents a defining landmark in glass, light, water and bright faces. In July last year, the city of Chicago unveiled its newest civic landmark: Millennium Park, a world-class artistic and architectural extravaganza in the heart of downtown. At a cost of more than $475 million and in a process that took more than six years to complete, the park transformed a lakefront space once marked by unsightly railroad tracks and ugly parking

When you execute complex projects for sophisticated clients, your ability to satisfy them and their tastes by bringing something different or interesting or unique to the table can make all the difference. As our firm has evolved, we've increasingly come to focus on identifying these compelling touches, which for us most often center on old-world influences that resonate, sometimes deeply, with our clients. I've always loved to travel and have spent extended periods in Asia, Latin America and Europe. At some point, it occurred to me that by working not only with the principles of classical European and Asian garden design, but also with authentic, imported materials and art objects, the work would take on greater meaning and interest for me - and for my clients as well. To that point, our firm had followed a path of influence that still reflects itself in our replication of ancient stone-setting techniques. While traveling in China and Japan, I began spotting stone pieces and other objects we could use directly in our watershapes and gardens and started acquiring pieces for that purpose. This step beyond evoking not only the style but actually using elements of authentic design quickly turned into a powerful element in our work. As we moved further in this direction, the channels opened wider, the creative possibilities blossomed and we soon began incorporating more and more of the materials and ideas that I'd encountered

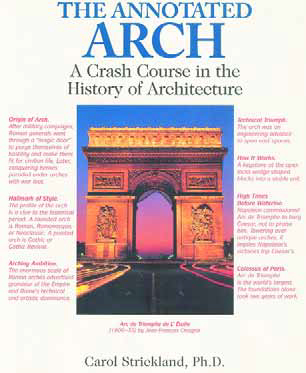

I don't know who first expressed it, but I've always welcomed the notion that "great designers are great thieves." That nugget rings so true because very few among us ever have completely original ideas and, in fact, the best designs are generally derivative of something that came before. To my mind, if some degree of larceny is part of our game as watershape designers, then one of the very best places to find borrowable ideas is a book entitled The Annotated Arch by the historian Carol Strickland (Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2001) - a wonderful and inspiring 180-page, beautifully illustrated book that offers a

Since the dawn of civilization, it has stood as the single most enduring of all artistic media: From representations of mythological characters and historic events to applications as purely architectural forms and fixtures, carved stone has been with us every step of the way. As modern observers, we treasure this heritage in the pyramids of Egypt and Mesoamerica. We see it in the Parthenon in Athens, in the Roman Colosseum and in India's Taj Mahal - every one of them among humankind's finest uses of carved stone in the creation of monuments and public buildings. As watershapers in particular, we stand in awe before the Trevi Fountain in Rome, the glorious waterworks of the Villa d'Este and the fountains of Versailles, three of history's most prominent examples of carved stone's use in conjunction with water. But you don't need to

When you look at this project in finished form, there's no way to see the months of struggle or the overall level of difficulty that went into its creation. You don't see the fact, for example, that we discovered while excavating the courtyard that the house itself was in imminent danger of collapsing. You don't see that the narrow access way buckled when we first started working, or the ugly trauma of the broken septic tank. You can't see the continuous changes in thought, direction and design that went into the deck, or the tremendous time and effort required to make the