ARTICLES

Advance Search

Aquatic Health

Aquatic Health, Fitness & Safety

Around the Internet

Aquatic Culture

Aquatic Technology

Artful Endeavors

Celebrity Corner

Life Aquatic

Must-See Watershapes

People with Cameras

Watershapes in the Headlines

Art/Architectural History

Book & Media Reviews

Commentaries, Interviews & Profiles

Concrete Science

Environment

Fountains

Geotechnical

Join the Dialogue

Landscape, Plants, Hardscape & Decks

Lighter Side

Ripples

Test Your Knowledge

The Aquatic Quiz

Other Waterfeatures (from birdbaths to lakes)

Outdoor Living, Fire Features, Amenities & Lighting

Plants

Ponds, Streams & Waterfalls

Pools & Spas

Professional Watershaping

Structures (Editor's Notes)

Travelogues & History

Water Chemistry

WaterShapes TV

WaterShapes World Blog

Web Links

Around the Internet

Aquatic Culture

Aquatic Technology

Artful Endeavors

Celebrity Corner

Life Aquatic

Must-See Watershapes

People with Cameras

Watershapes in the Headlines

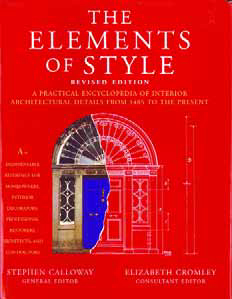

When people ask me how I approach the design process, I tell them it's always based on three things: The clients' ideas about what they want; the site's characteristics; and the architecture of the home. If I had to pick one of those factors that's been the most challenging for me to master, I'd have to say it's been gaining a firm grasp on architecture and the details that make up architectural styles. And when I've been asked where that kind of background can be gained in the form of a reference book, I've always been at something of a loss to make a recommendation. Basically, it's tough to narrow things down because architectural design is so huge a topic. Without an architect's educational background and training, I've been left to pick up what I can mostly by paying attention to what I see around me - a challenge in itself in my area, where most

Have you ever turned down a client who really wanted to work with you and you alone? It's a hard thing to do, which is why most of us have found ourselves at one time or another saying "yes" despite the fact that we believe something the clients want simply cannot be done or, more important, that we've developed serious doubts about them. Just at that point where we really need to sit them down and tell them to go away, many times we'll freeze - and here's the usual reason why: "If I tell them 'no,' then they'll just get someone else to do it and I'll lose the job!" Giving in to this fear of losing a project and letting apprehension guide our decisions in place of any faith we might have in our common sense or experience is

Have you ever turned down a client who really wanted to work with you and you alone? It's a hard thing to do, which is why most of us have found ourselves at one time or another saying "yes" despite the fact that we believe something the clients want simply cannot be done or, more important, that we've developed serious doubts about them. Just at that point where we really need to sit them down and tell them to go away, many times we'll freeze - and here's the usual reason why: "If I tell them 'no,' then they'll just get someone else to do it and I'll lose the job!" Giving in to this fear of losing a project and letting apprehension guide our decisions in place of any faith we might have in our common sense or experience is

All of us who started our own businesses decided at some point what our companies would be: We chose a focus, set guiding philosophies, developed credos, defined a company culture, settled into a working style and pursued success. One of the most important calls each of us made along the way had to do with how large or small our organizations would be. In fact, this decision has a lot to say about how any business runs and appears to the outside world: It influences the volume of business that can be accommodated, dictates management style, narrows or broadens the organizational structure and ultimately

All of us who started our own businesses decided at some point what our companies would be: We chose a focus, set guiding philosophies, developed credos, defined a company culture, settled into a working style and pursued success. One of the most important calls each of us made along the way had to do with how large or small our organizations would be. In fact, this decision has a lot to say about how any business runs and appears to the outside world: It influences the volume of business that can be accommodated, dictates management style, narrows or broadens the organizational structure and ultimately

In all great human endeavors from the arts to science and industry, we typically find small numbers of pioneers whose achievements are so astonishing that they inspire

In all great human endeavors from the arts to science and industry, we typically find small numbers of pioneers whose achievements are so astonishing that they inspire

Landscape-lighting design is my obsession: Not only do I make my living at it, but it has also reached a point where it informs the way I look at every landscape and watershape I encounter - whether I'm working on those spaces or not. When I visit almost any site - and particularly when I spot an interesting garden - I almost instantaneously begin formulating ideas about how I'd light it. That's a good thing, because it keeps me professionally sharp, but it's also a bit addictive: Once you start visualizing how dynamic particular places can be when properly lit, you get hooked on the mental exercise and start enjoying the intensity of the experience. In the beginning, of course, those clear visualizations