fountain design

Most people know Maya Lin for her bold design of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, but watershapers in particular should become familiar with a range of her other works as well. For nearly 15 years, reports William Hobbs, his company has been involved in producing intricate water effects for the famous artist, whose works draw fascinating connections between observers and the mysteries of time and nature. The marriage of water and art can be extremely powerful and evocative, especially in the hands of a great designer. One who has taken the use of water to sublime and fantastic levels is Maya Lin, the artist who rose to prominence as a

A watershape doesn't need to be immense to be either beautiful or monumental. Nor does it need to be outsized to serve its community as a gathering place or point of pride. Those are a couple of the lessons we learned in shaping the York Street Millennium Fountain in the heart of one of the highest profile tourist areas of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Using an inventive approach that balanced the needs of the neighborhood, a range of national and local government officials and the general citizenry's desire to celebrate the new millennium, the project also embraced the city's own rich history. The new fountain sits at a significant crossroads of pedestrian traffic between the Byward Market and the government district in downtown Ottawa. Indeed, the traffic island surrounding the fountain stands just blocks from Parliament Hill, the seat of Canada's national government, and was intended from the start to serve as a focal point and gathering place. Although small and comparatively simple, the project was complicated by the need to satisfy both local and national officials, which meant we had to incorporate

People don't usually have trouble with boundaries and will honor requests to "Keep Out," for example, or leave certain doors to "Employees Only." But there are also cases where we generally take issue with limitations on behavior whether stated or implied, and I can think of no better instance in which this takes place than with water in public spaces. Despite designers' best efforts over the years to make it clear where bathers are welcome and where they are not, the public has steadily defied boundaries by trespassing into waters that were never directly designed for human interaction. In fact, you might say that formal, decorative fountains are a forbidden fruit from which many of us have taken the occasional bite. During the past two decades, watershape designers have looked very specifically at the irresistible urge we have to touch water in an effort to shape all-new boundaries between public nuisance and design nuance. Along the way, we've learned which elements offer a deliberate, positive signal - a real "permission to play" - and are now wielding this power of interactivity to create and define a broad range of

Perhaps the hardest thing for a watershaper to accomplish is to take a set of someone else's drawings, plans, sections and elevations, roll them all around together and come up with an accurate, three-dimensional, living interpretation of an architect's vision. The project shown here is a prime example of what's involved in this process. Designed by senior landscape architect Patrick Smith of the Austin, Texas, firm of Richardson Verdoorn, the plans called for three separate streams ranging in length from 50 to 80 feet (with each dropping 36 inches over various weirs) - all converging on a rocky

Visiting Hearst Castle is an experience that sticks with you. Long before I became a watershape designer, I know that my childhood visits to this hilltop in Central California inspired and affected my thinking about art and architecture and the creative use of space long before I had any professional interest in those subjects. Every time I go - which is as often as I can - I'm impressed by a collection of art and architecture so rich and varied that I always find something new. For years, I've been amazed by the castle's two pools and their beautiful details, incredible tile and classic style. More recently, however, I've started paying closer attention to the other ways in which water is used on the property - and my appreciation for what I'm seeing grows every time I stop by. A BIT OF HISTORY William Randolph Hearst inherited the 250,000-acre ranch on which the castle was built from his mother, Phoebe Apperson Hearst, in 1919. The remote property hadn't seen much development to that point, but he soon began transforming it into a monument to American ambition and his passion for

Kansas City, Missouri, proudly calls itself "The City of Fountains," and it comes by the title legitimately. In fact, more than 150 public fountains grace its plazas, boulevards, parks and public buildings, and the community has long held to a tradition of creative use of moving water and sculpture in developing its public spaces. As a resident of the city, I get a sense of civic history and our collective self-image as I look at these fountains. As a watershaper, I take additional pride in the variety of forms and styles I see and in the course of technological development that has lifted fountains to new heights of

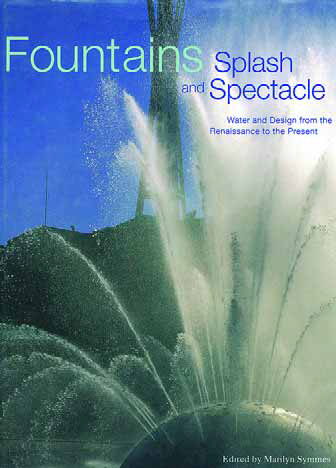

For anyone designing decorative water, Fountains: Splash and Spectacle is a wonderful and useful resource. This wonderfully illustrated anthology of essays on classic fountains (edited by Marilyn Symmes and published in 1998 by Rizzoli International Publishing, New York) deftly encompasses the range of fountain designs from antiquity to modern day. From the modest Alhambra in Spain to Chicago's dramatic Buckingham Memorial, Symmes and the book's contributors weave together scores of detailed examples illustrated with beautiful photos and, in many cases, supported by sets of plans, drawings and diagrams used in creating some of the world's most beautiful and historic watershapes. Rather than approach fountains in a purely chronological or geographic context, the book is organized into eight chapters covering

From the start, this project was meant to be something truly special - a monument symbolizing the ambition of an entire community as well as a fun gathering place for citizens of Cathedral City, Calif., a growing community located in the desert near Palm Springs. "The Fountain of Life," as the project is titled, features a central structure of three highly decorated stone bowls set atop columns rising into the desert sky. Water tumbles, sprays and cascades from these bowls and other jets on the center structure, spilling onto a soft surface surrounding the fountain. All around this vertical structure are sculpted animal figures - a whimsical counterbalance that lends a light touch to the composition and opens the whole setting to children at play. I've been building stone fountains for 18 years, and I've never come across anything even close to this project with respect to either size or sheer creativity. Making it all happen took an unusually high degree of collaboration on the part of the city, the artist, the architects and a variety of