ARTICLES

Advance Search

Aquatic Health

Aquatic Health, Fitness & Safety

Around the Internet

Aquatic Culture

Aquatic Technology

Artful Endeavors

Celebrity Corner

Life Aquatic

Must-See Watershapes

People with Cameras

Watershapes in the Headlines

Art/Architectural History

Book & Media Reviews

Commentaries, Interviews & Profiles

Concrete Science

Environment

Fountains

Geotechnical

Join the Dialogue

Landscape, Plants, Hardscape & Decks

Lighter Side

Ripples

Test Your Knowledge

The Aquatic Quiz

Other Waterfeatures (from birdbaths to lakes)

Outdoor Living, Fire Features, Amenities & Lighting

Plants

Ponds, Streams & Waterfalls

Pools & Spas

Professional Watershaping

Structures (Editor's Notes)

Travelogues & History

Water Chemistry

WaterShapes TV

WaterShapes World Blog

Web Links

Around the Internet

Aquatic Culture

Aquatic Technology

Artful Endeavors

Celebrity Corner

Life Aquatic

Must-See Watershapes

People with Cameras

Watershapes in the Headlines

Even though many swimming pools look similar in lots of fundamental ways, every one of them is actually quite unique. From soil and groundwater conditions or the specifics of their structural designs to the ways in which they have been installed, water-containing vessels of all shapes, types and sizes are, in fact, subject to a wide array of site- and workmanship-specific variables that can influence the way their concrete shells will perform through the years. When a watershape cracks, any number of things might have gone wrong. To the owner of a watershape, of course, such cracking is obviously a source of concern. The fix is often expensive, and it's not at all unusual for contractors to defend their work as a means of avoiding the necessity of paying to remedy the situation. This can leave the owner in a very difficult position in which experts must be called in to determine the true cause of the problem - and then he or she might be left alone to pressure the contractor who installed the vessel to take responsibility and

When I was a kid in Caltagirone, Sicily, everybody worked hard all the time - grueling manual labor in the fields and factories. By the time I was eight years old, I was already working with my father in a ceramic-sculpture foundry. I didn't do much more than sweep the floors, but I was around all sorts of craftspeople and began to see that there were some forms of hard work that were more fulfilling than others. So I began to think about becoming a painter. I took my first steps in that direction at 13. By the time I was 18, I'd opened a studio and was painting and sculpting on my own. In those days, the arts community was an exciting place where we shared ideas, fed on each others' energy and competed with each other for good commissions. I'm not ashamed to admit that I thought the established artists I hung out with were cool and powerful in their own ways - and that I wanted to be just like them. Given the specific nature of my art, it's not surprising that the great Italian masters heavily influenced my work right from the start, including Michelangelo, Raphael and especially Leonardo Da Vinci. They are my heroes, and I see the work I do as a modest continuation of the traditions they established. These artists taught me that great art is about passion and the desire to

My journey in the company of water began when I was about seven years old, as soon as I was old enough to explore the countryside near my family's farm in Southern England. It was then that I fell in love with water - wading in streams, making dams out of small rocks, sticks and mud and watching the fish darting in clear pools. Much of my summer vacation was spent on a sun-peeled green punt gliding on a lake and staring down to the bottom at the aquatic plants and water creatures. It was a formative experience. My parents loved the water, too, and they always had some type of boat. I'll never forget how almost every one of those modest vessels leaked profusely. This gave all of us first-hand experience of enjoying the water as we developed a visceral appreciation of the importance of

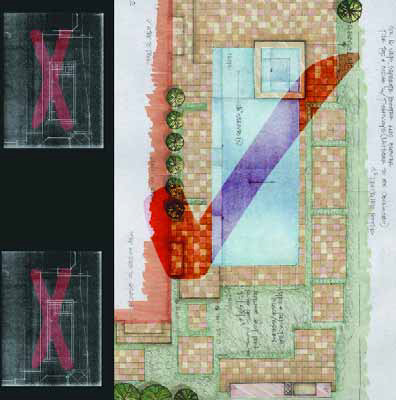

Back when I was still new to watershaping in the mid-1990s and working for a construction firm in Northern California, I was asked to review a project for a custom home under construction in Napa Valley. I was intrigued, partly because the identity of the client was a closely held secret and partly because all project information and bidding was flowing through an architect in Mexico City. But what really grabbed my attention was the set of plans for the home and grounds - just incredible! I'd never seen anything like it. The modernist-style home was based on big vertical and horizontal planes in brilliant colors. There were courtyard fountains, large rectilinear reflecting pools and a beautiful vanishing-edge swimming pool. The design was so outstanding that even when we missed out on the project, I held onto

Where you've come from often has everything to do with where you're going. As a case in point, let me describe a project that had its origins all the way back at the very start of my work as a watershaper. My pool industry career began soon after I graduated from college. At the time, I was living in a garage in a rough part of Los Angeles and really wasn't sure what I wanted to do. I had studied ancient history, three-dimensional design and industrial design and had been accepted as a PhD candidate in pharmacology at the University of the Pacific. I was convinced I wanted to be a designer, but I wasn't sure which field I should enter. Then one day, at a time when I was about as broke as an organ grinder without a monkey, I answered an ad in the newspaper looking for

Most of us are in business to earn a living, which is probably why so many of us think of the high-end market as the place to be. In general, of course, the bigger the job, the larger the paycheck will be. But when I look more closely at the work I've done through my career, I believe we might be overlooking valuable opportunities for personal and professional growth by being so single-minded in pursuing grand, big-ticket jobs. When I started my business 15 years ago, I was happy to find work on small borders in small spaces. Since then, I'm proud of the fact that I have worked my way up to designing for multiple-acre estates. To be sure, I much prefer having a few large jobs to a bunch of smaller ones, but

A couple months back, the National Association of Home Builders held its annual convention in Orlando, Fla. - a massive January affair that drew more than 120,000 attendees to view all manner of products falling under the broad umbrella of "home construction." One of the annual centerpieces of NAHB's event is the New American Home program. Each year, select local contractors build a state-of-the-art home in the show's host city to put the absolute cutting edge of residential design and construction on display. During the convention, show organizers sell tickets for tours, and thousands of people tour the home. Once the tours are concluded, the home is sold and becomes a deluxe private residence - and a lot of money from ticket sales flows to charity. I was fortunate enough to be asked to

Sometimes it's the most ordinary experiences that yield the most sublime memories - the pleasant surprise, a beautiful view, the warmth of the sun after a dip in the ocean. For me (and I suspect I'm not alone), these experiences occur

The Crown Fountain in Chicago's Millennium Park is an ingenious fusion of artistic vision and high-tech water effects in which sculptor Juame Plensa' s creative concepts were brought to life by an interdisciplinary team that included the waterfeature designers at Crystal Fountains. Here, Larry O'Hearn describes how the firm met the challenge and helped give Chicago's residents a defining landmark in glass, light, water and bright faces. In July last year, the city of Chicago unveiled its newest civic landmark: Millennium Park, a world-class artistic and architectural extravaganza in the heart of downtown. At a cost of more than $475 million and in a process that took more than six years to complete, the park transformed a lakefront space once marked by unsightly railroad tracks and ugly parking

So often, the art and science of invention begins with the study and appreciation of nature. While growing up in Wisconsin, I was repeatedly exposed to the naturally occurring islands often found floating on bodies of water amid the conifers in the northern, peat-bog region of the state. I couldn't help noticing that these islands were exactly the best places to go fishing. They were just terrific, presenting a structure under and around which fish, for whatever reason, loved to spend their time. Moreover, every floating island I've seen in nature is host to all sorts of flowering plants including American Speedwell, Monkey Flower, Blue Flag and even examples of the few native varieties of North American wild orchids along with incredible varieties of other broad-leaf plants, grasses and even trees. In many cases, I've seen species that don't abound in the surrounding environment but