Landscape, Plants, Hardscape & Decks

As a landscape designer and installer, I have an abiding fascination with stone. I love the feel of it and its myriad colors, veins, streaks, shapes and textures, and I particularly admire its strength and flexibility. We pave with it, sculpt it and run water over, under and through it. It doesn't need painting or much care, looks great with plant material and has, as those who work with stone will point out, a timeless quality that cannot be reproduced with artificial materials. The best thing about stone is that when you use even one piece in an aesthetically meaningful way, you've

Sometimes, it's the simple things that trip you up. As a case in point, I was recently called by a homeowner who was wondering why the tile was falling off the outside wall of a raised pool that had just been installed by another builder. Unfortunately, that builder apparently hadn't known how to pull off this standard detail. The pool had been raised eight inches out of the ground in keeping with the design intent. This is a detail I use frequently to create a seating area around pools, but I was a bit mystified by this particular choice of elevation: It was too high to be a step (most building codes call for maximum 7-1/2-inch outdoor risers) and too low to serve very well as a bench. (Actually, it was just about right for

With a busy schedule, it's too easy to use the same tools repeatedly in project designs. Yes, you can mitigate the repetition to a certain extent by using those tools differently each time, but the fact remains that many of us tend to design over and over again with the same plants, hardscape materials and structural approaches because it's what we know and trust. But let's face it: Most clients don't want exactly what someone else has; instead, they want one element from this garden and a special plant from that one. From a design perspective, selecting new plants every time is

Throughout my design career, I have repeatedly expressed to clients that their gardens are dynamic, constantly changing and only to a very minimal degree under anyone's control. You can plant, water, fertilize, cultivate and prune - "and if you're lucky," I say, "you'll enjoy the fruits of your labors in the form of a visual feast." But that's only if you're lucky, I continue, because no matter what we do to nurture gardens, they are always subject to the whims of Mother Nature. From the smallest annual to the most statuesque tree, no garden is immune. Even though I've always had this talk with clients, however, I've always held the mild belief that it's possible in some ways to stay a step ahead of her by being vigilant and active. I learned the other day at first hand that she

Quite often, my clients will preface our design discussions with the statement that they want to see flowers in bloom throughout the year. They just hate it, they say, when the garden looks "bare" from December to February. In my opinion, they're just not seeing the possibilities their gardens have to offer. In fact, winter is my favorite time of the year, and it's about more than the holidays, the gift giving (and receiving!) and the chilly temperatures: Mainly, it's about my love affair with winterscapes. It may be because I'm a northeasterner somewhere deep inside, but I love the fact that colder climates, with their snow and other weather inclemencies, require those with gardens to

My daughter and I just returned from our annual trip to visit family in Connecticut and used the occasion this time to travel all over the northeast - from Boothbay Harbor, Portland and Camden in Maine to Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket and other parts of Massachusetts as well as slices of New Hampshire and Rhode Island. I'm never disappointed by the beauty I find in that part of the country. The landscapes are much lusher than they are at home in southern California, a fact that drives home the point that I spend most of my time in a desert. The old-growth trees back east are

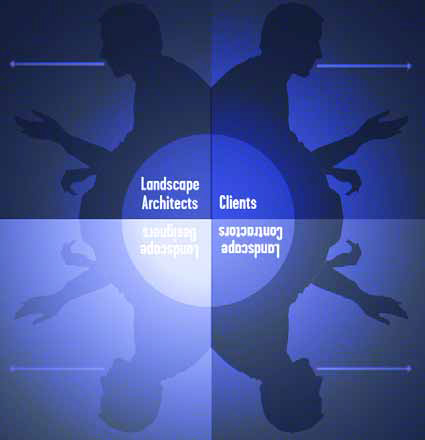

I recently wrote a Letter to the Editor of Landscape Architecture, the magazine of the American Society of Landscape Architects, in response to an editorial he wrote on the lack of interest among landscape architects in plant knowledge. The gist of his commentary was that, for too many years now, landscape architects had been focusing on hardscape and overall design and were reserving little creativity, interest, or care for botanical adornments. My response was a supportive rant, as this has been a pet peeve of mine for years and I strongly believe that

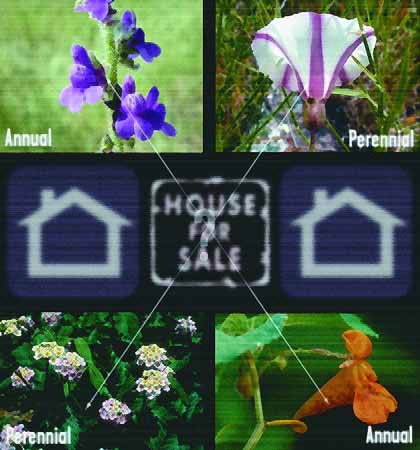

I recently received a call from a Wall Street Journal reporter who was doing a feature on preparing a home for sale. She told me she wanted a landscape designer's perspective on how homeowners should spend their money to get the most bang for the buck and really put me on the spot in the process: Her deadline was the following morning, and I had to do some fast thinking when her call came in at 8 pm. It immediately occurred to me that I always ask homeowners whether they are landscaping for