terminology

'As is true of many business sectors, the architecture, engineering and construction industry . . . has its own language,' noted Dave Peterson to start his March 2009 Currents column, 'and the construction documents generated by those professionals (watershapers very definitely included) are the medium through which everyone communicates. 'The challenge for watershapers is that we've

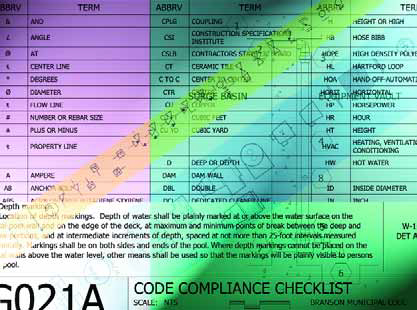

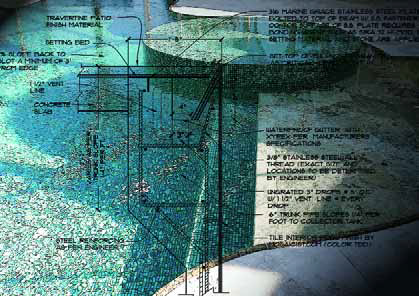

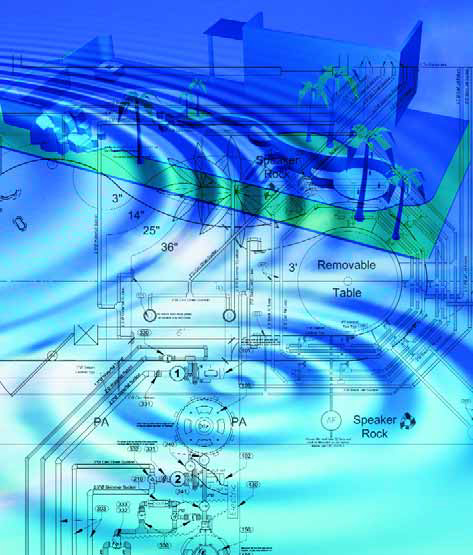

As is true of many business sectors, the architecture, engineering and construction industry (commonly and conveniently abbreviated as A/E/C) has its own language – and the construction documents generated by those professionals (watershapers very definitely included) are the medium through which everyone communicates. The challenge for watershapers is that we’ve come to the table a bit later than

It’s true for any watershaper: No matter how varied the work you do, it never hurts to be known for the ability to do something special – and for doing it exceptionally well. Through the years, for example, my firm has polished its ability to provide our clients with watershapes reflecting a wide variety of tastes, styles and features, but to an extent that sometimes surprises even me, we’re known among prospective clients for

It's true for any subject that it's basically impossible to teach and learn about a topic unless there's a shared set of terms that everyone understands and can agree about what they mean. I've thought about that fact a lot in developing a course for university students about watershaping, or what I'm most often calling "water architecture" these days. With watershaping as a subject, that sounds simple enough. After all, we all know the meaning of "swimming pool," "fountain" and "pond." Or do we? I'm not so sure anymore. When I started breaking down our vocabulary for classroom use, I quickly recognized that the meanings of the words we use are anything but clear. Indeed, the more I dug into this seemingly simple phase of curriculum development, the murkier things became.The difficulty I ran into was this: Once I moved past the most rudimentary sets of terms and definitions and looked closely at the language we use to describe what we produce, it became painfully obvious to me that

It's true for any subject that it's basically impossible to teach and learn about a topic unless there's a shared set of terms that everyone understands and can agree about what they mean. I've thought about that fact a lot in developing a course for university students about watershaping, or what I'm most often calling "water architecture" these days. With watershaping as a subject, that sounds simple enough. After all, we all know the meaning of "swimming pool," "fountain" and "pond." Or do we? I'm not so sure anymore. When I started breaking down our vocabulary for classroom use, I quickly recognized that the meanings of the words we use are anything but clear. Indeed, the more I dug into this seemingly simple phase of curriculum development, the murkier things became.The difficulty I ran into was this: Once I moved past the most rudimentary sets of terms and definitions and looked closely at the language we use to describe what we produce, it became painfully obvious to me that

It's a plain fact: In many regions of the United States these days, the vast majority of construction laborers speak Spanish. That's a big deal because, as watershapers, it is our responsibility to convey the design mission for our projects as well as all-important client wishes to these talented craftspeople - not to mention the basic, general communications that come with managing the work of individuals and small groups of people. Where I work in Texas, this is the simple reality - and I know it's true as well in California, Arizona, Florida, Nevada and many other parts of the country. As a consequence, I think it makes sense for those responsible for guiding the overall efforts of these workers to be able to communicate with them in their own language. After all, these are the folks who are installing the details we've so carefully designed and engineered. For my part, I'm trying to elevate my communications skills by

What do you call the effect of water falling over the edge of a pool? Do you say it has a negative edge? An infinity edge? A vanishing edge? Or do you have

As a former shotcrete builder myself, I believe you can't find a better method of building a pool, spa, pond or waterfeature of any type than by using pneumatically placed concrete, or "shotcrete." The method and the material offer the designer and builder great and often incredible design flexibility, and the resulting watershapes will last several lifetimes. Given that the vast majority of watershapers around the world depend on shotcrete as their primary construction material, it only makes sense that we should know as much as possible about putting this amazing product to its best possible use. Unfortunately, however, that's not always the case. There's little argument that the process of shotcrete construction is laborious and demanding, that it requires a major logistical and physical effort and that fairly precise timing is necessary. For all the focus it takes to apply it and shape it just so, however, I have observed a couple of critical steps many builders overlook in the press of getting the job done - the most important of them being the proper curing of the