Kansas City, Missouri, proudly calls itself "The City of Fountains," and it comes by the title legitimately. In fact, more than 150 public fountains grace its plazas, boulevards, parks and public buildings, and the community has long held to a tradition of creative use of moving water and sculpture in developing its public spaces. As a resident of the city, I get a sense of civic history and our collective self-image as I look at these fountains. As a watershaper, I take additional pride in the variety of forms and styles I see and in the course of technological development that has lifted fountains to new heights of

The Getty Center is a true multi-media experience: imposing architecture, lots of people, incredible materials of construction, amazing views, diverse spaces, rich and varied sounds - and it's mostly all a bonus, because none of this has much to do with the Los Angeles center's core functions as museum and research institution. Designed by architect Richard Meier, the 750-acre campus is dominated by outsized structures wrapped in travertine, glass and enameled aluminum. It's all a bit cold (maybe time will soften the sharper edges and

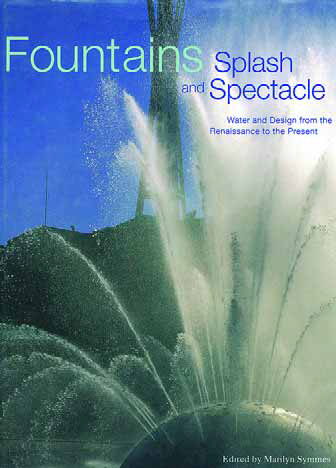

For anyone designing decorative water, Fountains: Splash and Spectacle is a wonderful and useful resource. This wonderfully illustrated anthology of essays on classic fountains (edited by Marilyn Symmes and published in 1998 by Rizzoli International Publishing, New York) deftly encompasses the range of fountain designs from antiquity to modern day. From the modest Alhambra in Spain to Chicago's dramatic Buckingham Memorial, Symmes and the book's contributors weave together scores of detailed examples illustrated with beautiful photos and, in many cases, supported by sets of plans, drawings and diagrams used in creating some of the world's most beautiful and historic watershapes. Rather than approach fountains in a purely chronological or geographic context, the book is organized into eight chapters covering

People who know me are aware of the fact that I can be quite outspoken. They know I've been extremely critical of the pool and spa industry and have made it my crusade to argue that, as an industry, we need to elevate our game. My particular concern lately has to do with the areas of design and presentation. Before I get started, please note that what I'm about to say is directed mainly to readers who come to WaterShapes through what is traditionally labeled as the pool and spa industry. (To be sure, this information should also be of interest to those of you who come to watershaping from the landscape industry because it

Last month, we dug into the use of containers and accessories in garden designs and discussed ways in which they add interest, depth and dimension to almost any setting. This time, we'll get more specific and look at ways in which the same containers and accessories can be adapted to fit a particular environment and used with various design styles. To do so, let's start with long, rectangular pools (15 by 40 feet), place them in the yards of clients with different desires and see how we can blend planters into several popular styles: [ ] Contemporary: If you have a very contemporary setting with no planting beds, containers can be used to

Lately I've been finding myself in what seems like a fairly unique position: On the one hand, I work as a design consultant for architects and as a designer for high-end customers; on the other, I work as a builder executing the designs that customers and their architects choose. In this dual capacity, I've been able to gather a tremendous amount of input from construction clients and transfer it in one form or another as a consultant. I also have had the opportunity of seeing how decisions made in the design process play out during the construction process. Seeing both sides has led me to certain conclusions, chief among them

Throughout recorded history, great societies have built monuments to celebrate their victories, commemorate their tragedies and express their guiding ideals. Through creation of these great works of art or

It's one of the most famous buildings in the world, but few people know that Frank Lloyd Wright designed Fallingwater in a matter of hours. In 1935, when Wright first received the commission to design and build a vacation home for Pittsburgh retail tycoon Edgar J. Kaufman and his family in Mill Run, Pa., he didn't get to the project right away. After several months of preliminary discussions and delays, Kaufman decided to force the issue, telephoning the architect and saying that he was going to visit Wright's studio to see what had been done. It was at that point Wright decided he'd better design the house. He had a weekend. The construction process was no more direct, but it took longer. Work began in 1936 and was completed by 1939 in a series of costly fits and starts. The project was originally set to cost in the neighborhood of $40,000, but the final tally rose to nearly ten times that amount - not inconsiderable in post-Depression America. The result of the dramatic (and, at times, traumatic) process of design and construction is nothing less than one of the greatest achievements in American architecture, a work so compelling that it never stops

It's one of the most famous buildings in the world, but few people know that Frank Lloyd Wright designed Fallingwater in a matter of hours. In 1935, when Wright first received the commission to design and build a vacation home for Pittsburgh retail tycoon Edgar J. Kaufman and his family in Mill Run, Pa., he didn't get to the project right away. After several months of preliminary discussions and delays, Kaufman decided to force the issue, telephoning the architect and saying that he was going to visit Wright's studio to see what had been done. It was at that point Wright decided he'd better design the house. He had a weekend. The construction process was no more direct, but it took longer. Work began in 1936 and was completed by 1939 in a series of costly fits and starts. The project was originally set to cost in the neighborhood of $40,000, but the final tally rose to nearly ten times that amount - not inconsiderable in post-Depression America. The result of the dramatic (and, at times, traumatic) process of design and construction is nothing less than one of the greatest achievements in American architecture, a work so compelling that it never stops

From the start, this project was meant to be something truly special - a monument symbolizing the ambition of an entire community as well as a fun gathering place for citizens of Cathedral City, Calif., a growing community located in the desert near Palm Springs. "The Fountain of Life," as the project is titled, features a central structure of three highly decorated stone bowls set atop columns rising into the desert sky. Water tumbles, sprays and cascades from these bowls and other jets on the center structure, spilling onto a soft surface surrounding the fountain. All around this vertical structure are sculpted animal figures - a whimsical counterbalance that lends a light touch to the composition and opens the whole setting to children at play. I've been building stone fountains for 18 years, and I've never come across anything even close to this project with respect to either size or sheer creativity. Making it all happen took an unusually high degree of collaboration on the part of the city, the artist, the architects and a variety of