ARTICLES

Advance Search

Aquatic Health

Aquatic Health, Fitness & Safety

Around the Internet

Aquatic Culture

Aquatic Technology

Artful Endeavors

Celebrity Corner

Life Aquatic

Must-See Watershapes

People with Cameras

Watershapes in the Headlines

Art/Architectural History

Book & Media Reviews

Commentaries, Interviews & Profiles

Concrete Science

Environment

Fountains

Geotechnical

Join the Dialogue

Landscape, Plants, Hardscape & Decks

Lighter Side

Ripples

Test Your Knowledge

The Aquatic Quiz

Other Waterfeatures (from birdbaths to lakes)

Outdoor Living, Fire Features, Amenities & Lighting

Plants

Ponds, Streams & Waterfalls

Pools & Spas

Professional Watershaping

Structures (Editor's Notes)

Travelogues & History

Water Chemistry

WaterShapes TV

WaterShapes World Blog

Web Links

Around the Internet

Aquatic Culture

Aquatic Technology

Artful Endeavors

Celebrity Corner

Life Aquatic

Must-See Watershapes

People with Cameras

Watershapes in the Headlines

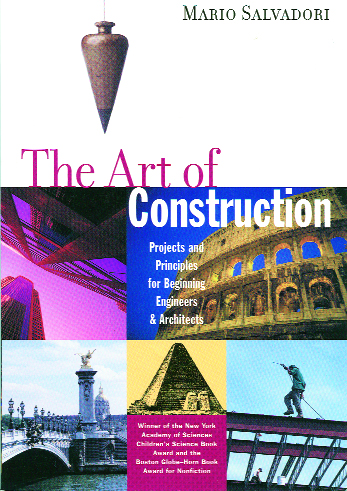

Most watershapers know that the work we do requires knowledge across a wide range of disciplines - a cluster of skills that includes, among others, geology, materials science, structural engineering, construction techniques, hydraulics, architecture, art history, color theory, drafting and more. As jacks of all trades, we don't really need to be "expert" on all of these fronts, but without a working knowledge of the technical and aesthetic disciplines involved in creating quality work, it's difficult to ensure the success of any given project. There's no question that some of us are better at certain disciplines than others, and it's up to us to recognize our strengths and weaknesses and fill in the gaps of our understanding as best we can. When it comes to structural engineering, for example, few of us qualify as bona fide engineers: That takes years of schooling and rigorous licensing processes. But almost all of us work with precise structural designs that are specific to the vessels and associated structures we design and/or build. In other words, we may not be engineers, but we sure as heck need to

Most watershapers know that the work we do requires knowledge across a wide range of disciplines - a cluster of skills that includes, among others, geology, materials science, structural engineering, construction techniques, hydraulics, architecture, art history, color theory, drafting and more. As jacks of all trades, we don't really need to be "expert" on all of these fronts, but without a working knowledge of the technical and aesthetic disciplines involved in creating quality work, it's difficult to ensure the success of any given project. There's no question that some of us are better at certain disciplines than others, and it's up to us to recognize our strengths and weaknesses and fill in the gaps of our understanding as best we can. When it comes to structural engineering, for example, few of us qualify as bona fide engineers: That takes years of schooling and rigorous licensing processes. But almost all of us work with precise structural designs that are specific to the vessels and associated structures we design and/or build. In other words, we may not be engineers, but we sure as heck need to

From the moment I set foot on this site perched on the bluffs at Del Mar, Calif., I just knew I would be the designer chosen to develop the garden: I was energized simply by being there and, more important, was at ease with the owners from the start. Immediately noticeable was the way the whole property sloped down from street level to the top of

Through the years in these pages and elsewhere, I've been a persistent critic of the shortcomings of the watershaping trades in general - and especially of the pool and spa industry in which I've operated for more than 25 years. Sometimes I've been harsher than others, but my intent has invariably been to define the difference between quality work that elevates the trade and the junk that's held back our industry's reputation. I've never named names, but I've been particularly hard on practitioners who seem eternally stuck in old ways of thinking and working: Their work seldom lines up with the best efforts of which the industry is capable. Just recently, I had a long talk with WaterShapes' editor in which we discussed the development of a new approach to

Through the years in these pages and elsewhere, I've been a persistent critic of the shortcomings of the watershaping trades in general - and especially of the pool and spa industry in which I've operated for more than 25 years. Sometimes I've been harsher than others, but my intent has invariably been to define the difference between quality work that elevates the trade and the junk that's held back our industry's reputation. I've never named names, but I've been particularly hard on practitioners who seem eternally stuck in old ways of thinking and working: Their work seldom lines up with the best efforts of which the industry is capable. Just recently, I had a long talk with WaterShapes' editor in which we discussed the development of a new approach to

On just about any site, we run into hidden obstacles - everything from underground pipes or leftover debris from other construction to myriad other surprises - and many of them are easily dealt with either by removing the barriers or redirecting things around them. But what happens when the obstacle is alive and growing and you can't remove it or escape from it? In these situations, you have to do your research, get creative and, above all, take the matter seriously. Case in point is a garden I'm designing for a project with David Tisherman - the one discussed previously where I'm developing a white

On just about any site, we run into hidden obstacles - everything from underground pipes or leftover debris from other construction to myriad other surprises - and many of them are easily dealt with either by removing the barriers or redirecting things around them. But what happens when the obstacle is alive and growing and you can't remove it or escape from it? In these situations, you have to do your research, get creative and, above all, take the matter seriously. Case in point is a garden I'm designing for a project with David Tisherman - the one discussed previously where I'm developing a white

It was an unusual time to be thinking about work, but there I was on a late-August morning, and Peak's Island off the coast of Maine was in glorious summer form. Small enough to walk around in an hour or so, the island is filled with delightful, charming summer cottages - not a "McMansion" in sight. In the early light, my thoughts had been silenced as I savored the beauty of the coastal wetlands and meadows filled with wildflowers, grasses and sedge. I was totally absorbed by the

We landshapers can and should attach a dollar figure to our knowledge, experience and integrity. That's a lesson I had to learn the hard way. About fifteen years ago, I was in need of a new dump truck for my growing business. I wasn't rich, so I decided to buy a used vehicle and found one in the local truck-trader newspaper. After looking at the truck with my trusty mechanic, I made an offer to my fellow landscape contractor, and he accepted. As we entered his office to complete the necessary paperwork, I came face-to-face with a landscape plan that looked very familiar: It was one I had drawn for potential clients. In fact, it was the colored plan I had presented to them only a few weeks earlier. I felt violated: That was my plan sitting on his desk. I asked him where he'd gotten it - an obvious and unnecessary question - and he told me that

Sometimes, just when you think you have things all figured out, something comes along to transform your point of view. For as long as I've been a part of the watershaping trades in general and the pool/spa industry in particular, there have been those special occasions when I've had just the kind of experience that has caused me to see things with fresh eyes. Case in point is the trip I mentioned in my last column - the one in which I was heading to