clarity

I think we can all agree that design communication between architects, engineers, designers and contractors should be clear and concise. If that’s the case, it follows that plans and other construction documents should be uniform in their organization and layout – in other words, that they should follow a set of standards to which everyone in the design/construction community can and will adhere. Why the bother? The plain fact is that any given project involves a cast of characters that will be different – sometimes completely so – from just about any other project. This is why I’m such a strong advocate for

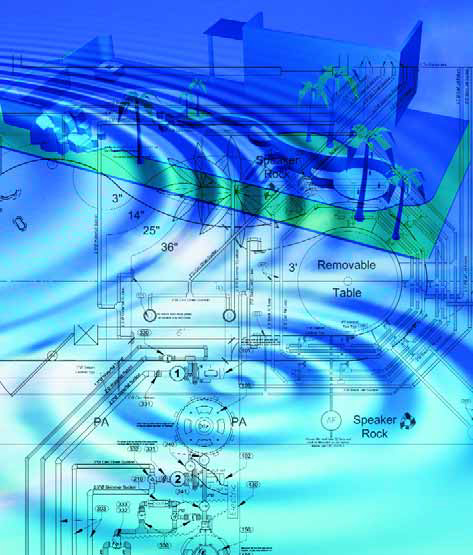

The most important skill needed by any designer is the ability to communicate clearly. This skill takes many forms, from verbal descriptions, well-assembled photographs and material samples to graphical depictions of concepts, details, dimensioned layouts and other drawn elements. When a watershaper is pushing design limits, in fact, he or she is often called upon to use all of these communication tools to convey ideas and aspire to offer something unique. In recent years, computer-aided design (CAD) systems have become increasingly popular as a tool in preparing construction drawings. Combined with the designer's creativity, these programs assist greatly in the production of plans. Unfortunately, however, our usage of them varies greatly in style and content from project to project and designer to designer. Indeed, these variations can be so radical that some plans are not easily understood by other professionals; moreover, the exchange of electronic CAD files is not always as convenient or efficient as it should be. This is why a group of industry experts has banded together to create the National CAD Standard (NCS), which is the core subject of this brief series of articles. That effort, which has met

The most important skill needed by any designer is the ability to communicate clearly. This skill takes many forms, from verbal descriptions, well-assembled photographs and material samples to graphical depictions of concepts, details, dimensioned layouts and other drawn elements. When a watershaper is pushing design limits, in fact, he or she is often called upon to use all of these communication tools to convey ideas and aspire to offer something unique. In recent years, computer-aided design (CAD) systems have become increasingly popular as a tool in preparing construction drawings. Combined with the designer's creativity, these programs assist greatly in the production of plans. Unfortunately, however, our usage of them varies greatly in style and content from project to project and designer to designer. Indeed, these variations can be so radical that some plans are not easily understood by other professionals; moreover, the exchange of electronic CAD files is not always as convenient or efficient as it should be. This is why a group of industry experts has banded together to create the National CAD Standard (NCS), which is the core subject of this brief series of articles. That effort, which has met

It's true for any subject that it's basically impossible to teach and learn about a topic unless there's a shared set of terms that everyone understands and can agree about what they mean. I've thought about that fact a lot in developing a course for university students about watershaping, or what I'm most often calling "water architecture" these days. With watershaping as a subject, that sounds simple enough. After all, we all know the meaning of "swimming pool," "fountain" and "pond." Or do we? I'm not so sure anymore. When I started breaking down our vocabulary for classroom use, I quickly recognized that the meanings of the words we use are anything but clear. Indeed, the more I dug into this seemingly simple phase of curriculum development, the murkier things became.The difficulty I ran into was this: Once I moved past the most rudimentary sets of terms and definitions and looked closely at the language we use to describe what we produce, it became painfully obvious to me that

It's true for any subject that it's basically impossible to teach and learn about a topic unless there's a shared set of terms that everyone understands and can agree about what they mean. I've thought about that fact a lot in developing a course for university students about watershaping, or what I'm most often calling "water architecture" these days. With watershaping as a subject, that sounds simple enough. After all, we all know the meaning of "swimming pool," "fountain" and "pond." Or do we? I'm not so sure anymore. When I started breaking down our vocabulary for classroom use, I quickly recognized that the meanings of the words we use are anything but clear. Indeed, the more I dug into this seemingly simple phase of curriculum development, the murkier things became.The difficulty I ran into was this: Once I moved past the most rudimentary sets of terms and definitions and looked closely at the language we use to describe what we produce, it became painfully obvious to me that

For a long time, I've studied a small lake that formed long ago in a natural bowl in Northern Wisconsin. It has about 20 acres of surface area and is now surrounded by a cow pasture and a cornfield. Holsteins graze right up to the water's edge and at times step into the lake to drink. Sometimes, cows being cows, their waste ends up in the water as well. On the opposite shore, the cornfield has an unusual configuration, with its furrows running straight down the slope and into the lake. When it rains or the fields are irrigated, some fertilizer inevitably washes into the lake. The stage is set for aquatic misery: Viscous, pea-soup mats of green algae and foul odors are the common results of this sort of nutrient loading. Indeed, few life forms other than algae survive in

For a long time, I've studied a small lake that formed long ago in a natural bowl in Northern Wisconsin. It has about 20 acres of surface area and is now surrounded by a cow pasture and a cornfield. Holsteins graze right up to the water's edge and at times step into the lake to drink. Sometimes, cows being cows, their waste ends up in the water as well. On the opposite shore, the cornfield has an unusual configuration, with its furrows running straight down the slope and into the lake. When it rains or the fields are irrigated, some fertilizer inevitably washes into the lake. The stage is set for aquatic misery: Viscous, pea-soup mats of green algae and foul odors are the common results of this sort of nutrient loading. Indeed, few life forms other than algae survive in

Many watershapers have a single-minded focus, doing all they can to deliver quality shells and surrounding decks to their clients. Quite often, however, that narrow focus means that inadequate space is left for planting - a problem I face quite often as a landshaper. It's clear in many cases that no thought at all was given to the landscape - and certain that no design professional was consulted before laying out and installing the hardscape. The result all too often is that there simply isn't enough room to allow for good-size planter beds. I often find myself rolling my eyes and lamenting the missed opportunities to

Many watershapers have a single-minded focus, doing all they can to deliver quality shells and surrounding decks to their clients. Quite often, however, that narrow focus means that inadequate space is left for planting - a problem I face quite often as a landshaper. It's clear in many cases that no thought at all was given to the landscape - and certain that no design professional was consulted before laying out and installing the hardscape. The result all too often is that there simply isn't enough room to allow for good-size planter beds. I often find myself rolling my eyes and lamenting the missed opportunities to

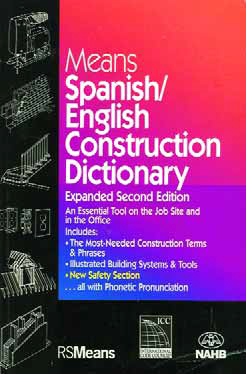

It's a plain fact: In many regions of the United States these days, the vast majority of construction laborers speak Spanish. That's a big deal because, as watershapers, it is our responsibility to convey the design mission for our projects as well as all-important client wishes to these talented craftspeople - not to mention the basic, general communications that come with managing the work of individuals and small groups of people. Where I work in Texas, this is the simple reality - and I know it's true as well in California, Arizona, Florida, Nevada and many other parts of the country. As a consequence, I think it makes sense for those responsible for guiding the overall efforts of these workers to be able to communicate with them in their own language. After all, these are the folks who are installing the details we've so carefully designed and engineered. For my part, I'm trying to elevate my communications skills by