engineering

Sometimes, the main idea that will drive a design jumps to mind as soon as you see the site. That was the case with the project covered here: When I pulled up to the gate of the property - high in the affluent hills of Bel Air, Calif. - what I found wasn't a big, showy home of the sort that have increasingly come to characterize the neighborhood; instead, what I saw was a place defined by subtlety and elegance. It all started with the gate's beautiful brick pilaster, beyond which I could just glimpse a large, lovely home with the distinctive architecture of an English manor house. Even though I hadn't met the clients yet or seen the entire job site, I was already convinced that the project would be

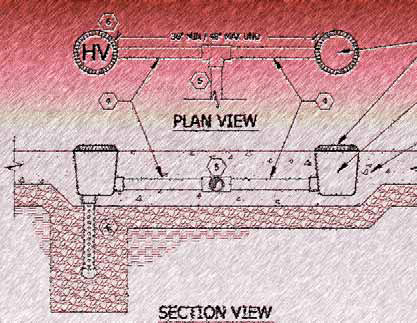

I hadn't planned on breaking away from my coverage of the National CAD Standard anytime soon, but recent events - including the arrest of a pool builder on charges of manslaughter in a suction-entrapment incident - compelled me to do otherwise. As I started composing this column, my plan was to call it "Entrapment Rundown" and make it a straightforward, positive summary of recent changes in codes and systems related to suction entrapment. As I dug more deeply into the topic, however, I found the issues and solutions to be much more confusing than I'd anticipated - so much so that

I hadn't planned on breaking away from my coverage of the National CAD Standard anytime soon, but recent events - including the arrest of a pool builder on charges of manslaughter in a suction-entrapment incident - compelled me to do otherwise. As I started composing this column, my plan was to call it "Entrapment Rundown" and make it a straightforward, positive summary of recent changes in codes and systems related to suction entrapment. As I dug more deeply into the topic, however, I found the issues and solutions to be much more confusing than I'd anticipated - so much so that

As a sculptor, I always seek ways to use my work to create positive (and sometimes intellectually challenging) experiences for those who have the opportunity to see what I've done. In my case, most of the time I'm not trying to make direct, narrative or literal statements. Instead, I seek to conjure feelings of fascination that lead to appreciation and enjoyment: You don't necessarily have to understand the forms I create to walk away from them with good feelings. When I have the opportunity to work in public settings (as was the case in the project featured on these pages), I'm stimulated by the idea that large numbers of people will be exposed to my sculpture and that, in many cases, those people will be exposed to what I've done over and over again because they'll be passing by at least twice each day as they go to and from their jobs in adjacent buildings. In this case, I was working next to an office tower in Century City - a famous business and entertainment district near downtown Los Angeles - which meant that thousands would repeatedly be walking right past my work and would come to accept it as part of their daily lives. In that light, I see art set amid architecture as a permanent commitment, as a cultural reference that has the potential to resound for generations. This recognition fills me with a heightened sense of

As a sculptor, I always seek ways to use my work to create positive (and sometimes intellectually challenging) experiences for those who have the opportunity to see what I've done. In my case, most of the time I'm not trying to make direct, narrative or literal statements. Instead, I seek to conjure feelings of fascination that lead to appreciation and enjoyment: You don't necessarily have to understand the forms I create to walk away from them with good feelings. When I have the opportunity to work in public settings (as was the case in the project featured on these pages), I'm stimulated by the idea that large numbers of people will be exposed to my sculpture and that, in many cases, those people will be exposed to what I've done over and over again because they'll be passing by at least twice each day as they go to and from their jobs in adjacent buildings. In this case, I was working next to an office tower in Century City - a famous business and entertainment district near downtown Los Angeles - which meant that thousands would repeatedly be walking right past my work and would come to accept it as part of their daily lives. In that light, I see art set amid architecture as a permanent commitment, as a cultural reference that has the potential to resound for generations. This recognition fills me with a heightened sense of

Echo Park is one of those places that has come to be defined by an all-too-familiar litany of urban woes: gangs, crime, violence, graffiti and drugs set amid aging buildings and a crumbling infrastructure. Fortunately, the community also has leadership that's working hard to change things for the better. One of the recent and most significant efforts to improve the lives of its citizenry involved renovating Echo Park Deep Pool, the area's only public swimming facility. The $6-million program involved enclosing the big pool with a new

Echo Park is one of those places that has come to be defined by an all-too-familiar litany of urban woes: gangs, crime, violence, graffiti and drugs set amid aging buildings and a crumbling infrastructure. Fortunately, the community also has leadership that's working hard to change things for the better. One of the recent and most significant efforts to improve the lives of its citizenry involved renovating Echo Park Deep Pool, the area's only public swimming facility. The $6-million program involved enclosing the big pool with a new

Given the fact that swimming pools and most other watershapes are placed in the ground, I've long been of the opinion that it's incumbent upon all of us who design and build them to have a basic understanding of soils science and geology. As has been stated in this magazine and elsewhere more times than I can count, the nature of the ground we build in (or on) has everything to do with the structures we design. Indeed, the composition and structure of the soils we encounter may well be the most fundamental of all the technical issue we ever face. Simply put, a watershape that's properly engineered in light of prevailing soil conditions will endure, while one that isn't runs a significant and often inevitable risk of structural failure. Relatively few of us who read WaterShapes are civil engineers, soils scientists or geologists, but all of us

Reading WaterShapes' 100th issue brought back memories of when I first discovered the magazine and my early conversations with its editor, Eric Herman. I remember thinking at that time - or at least hoping - that there really were lots of other people out there in the design/build world who truly aim to do things right, first time, every time. In looking over the poster included with the issue, I spotted the one from January 2000 with a photograph I'd taken of one of our projects - a retaining wall under construction. I don't know quite why, but that image made me think of a site I visited last year where a retaining wall built by inexperienced hands was in the process of collapsing. And not only was the wall falling apart, but it was also compromising the fence atop it as well as a concrete patio, a storage shed and an inground pool it was intended to bolster. I couldn't help thinking that, as far as our industry has come in the past decade, there are always going to be those who

I see gardens as entire worlds unto themselves - as complete and alive and distinct rather than as simple decorative extensions of architecture. Whatever form they might take, these spaces should carry us back into the peaceful parts of ourselves and to the calm, clear realms of our minds and spirits. This outlook has, in my role as founder and principal of Marpa Design Studio of Boulder, Colo., led me to consider landscapes as integrated wholes rather than as cobbled assemblies of solutions to various problems. It's a positive philosophy and design approach that is fully on display in the project depicted on these pages. I was recommended by the architect, who was working with the owners of this sprawling Rocky Mountain estate on a major renovation of both the home and the surrounding land. From the start, I was told there was just one major theme in mind: The home and its surroundings were to look as natural as possible - as though everything had arisen organically from the roots of the mountains. Neither house nor grounds possessed that spirit at the time, and the landscape was particularly deficient. Indeed, the only pre-existing feature was a cracked