Ponds, Streams & Waterfalls

For a long time, I've studied a small lake that formed long ago in a natural bowl in Northern Wisconsin. It has about 20 acres of surface area and is now surrounded by a cow pasture and a cornfield. Holsteins graze right up to the water's edge and at times step into the lake to drink. Sometimes, cows being cows, their waste ends up in the water as well. On the opposite shore, the cornfield has an unusual configuration, with its furrows running straight down the slope and into the lake. When it rains or the fields are irrigated, some fertilizer inevitably washes into the lake. The stage is set for aquatic misery: Viscous, pea-soup mats of green algae and foul odors are the common results of this sort of nutrient loading. Indeed, few life forms other than algae survive in

I've always believed that if you're going to do something, you should do it so well that the results are beyond compare. That basic philosophy has guided our company, GCS of Woodbridge, Calif., from the very start. It has led us to apply the highest standards to every one of our projects, all of which have been executed on large estates for ambitious, affluent, selective clients who invariably want something no one else has. We've been selective from the start as well, seeking clients who are in the process of creating the homes of their dreams and who want to have fun with (and in) their exterior spaces. In most cases, what they want are true oases - resort-like settings that give them a taste of

I've always believed that if you're going to do something, you should do it so well that the results are beyond compare. That basic philosophy has guided our company, GCS of Woodbridge, Calif., from the very start. It has led us to apply the highest standards to every one of our projects, all of which have been executed on large estates for ambitious, affluent, selective clients who invariably want something no one else has. We've been selective from the start as well, seeking clients who are in the process of creating the homes of their dreams and who want to have fun with (and in) their exterior spaces. In most cases, what they want are true oases - resort-like settings that give them a taste of

In all my many years of working with water, I've never grown tired of its remarkable beauty and complexity - or of the variations it encompasses, the ways it changes and the endless fascination it offers to those who come into its presence. At the heart of water's ability to inspire us and rivet our attention is its capacity to reflect. There's something truly magical about the way water mirrors the sky, a surrounding landscape, nearby architecture or a well-placed work of art. It's a gift of sorts, a timeless bounty that has captured imaginations ever since Narcissus fell in love with

In all my many years of working with water, I've never grown tired of its remarkable beauty and complexity - or of the variations it encompasses, the ways it changes and the endless fascination it offers to those who come into its presence. At the heart of water's ability to inspire us and rivet our attention is its capacity to reflect. There's something truly magical about the way water mirrors the sky, a surrounding landscape, nearby architecture or a well-placed work of art. It's a gift of sorts, a timeless bounty that has captured imaginations ever since Narcissus fell in love with

Creating watershapes and landscapes that are natural in appearance is always a challenge, says Ken Alperstein of Pinnacle Design, a firm that specializes in high-end projects related to top-flight golf courses. For this project in Shady Canyon, however, the ante was upped considerably by the site's location in an environmentally sensitive coastal canyon in southern California - a design challenge intensified by regulatory scrutiny every step of the way. It was a job that forced everyone involved to be on exactly the same page at all times. The landscapes and watershapes at the Shady Canyon Golf Club in Irvine, Calif., were developed by the Irvine Company as the heart of an upscale residential community. The wilderness area set aside for the course and its immediate surroundings had a subtle, bucolic charm all its own - a character the design team needed to

Whether we function as designers or builders or both, we watershapers tend to be flexible folk: We mold ourselves to projects and situations and tasks when we're called on to apply our skills and experience, and this often leads us to perform in unanticipated ways. This sort of adaptability is a way of life for most of us: It's a talent we use to produce success. But even the most adaptable practitioners of the watershaping arts will, every once in a while, encounter a project that shocks the system, alters all formulas and breaks down familiar parameters. In these rare cases, just surviving the process is an accomplishment that brings a sense of relief as well as a sense of amazement that both you and the project made it through to completion. I was recently fortunate enough to be part of just such a project - a fascinating set of challenges now known as the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. It's the last museum that will be

Every year, it seems, I'm asked to teach more and more classes on how to build streams, waterfalls and ponds that look natural. I enjoy conducting these sessions for local supply houses, landscape architecture firms, community colleges and other organizations and find it flattering that they value what I know. My motivation for sharing, however, is less about ego gratification than it is about my awareness that there's no way a single company can build all of the naturalistic watershapes consumers want these days. To me, it's a matter of collective as well as personal interest that these watershapes be built to function well and look great. In Colorado in particular, I also see a need for work that appears completely and distinctly natural, simply because most clients here are accustomed to seeing remarkable beauty in the countless alpine settings that grace this beautiful state. Indeed, it's a fact of professional life here that the work must mimic nature closely or it just won't fly. That can be very good for business, of course, but only if more than a few professionals hereabouts are up to the challenge. Available projects range from those that use thousands of

It certainly doesn't happen very often, but sometimes the addition of a watershape can completely redefine the way a property is perceived. In the case seen here, a nine-acre estate in the mountains above of Malibu, Calif., was zoned for agriculture. The owner's intention in buying it was quite appropriate: He wanted to turn it into a working vineyard brought to life visually by a big stream, pond and waterfall system. Once the watershape took form, however, the owner was so inspired by what he saw that his vision for the property changed and he recast the place as a venue for weddings and other events that would be enhanced by the bucolic, utterly romantic surroundings. In a very direct way, in other words, the watershapes served to increase both the aesthetic and financial value of the property. I'm a romantic at heart, so the notion that the work on display here will be a backdrop for special, memorable occasions has made the big, complicated project even more

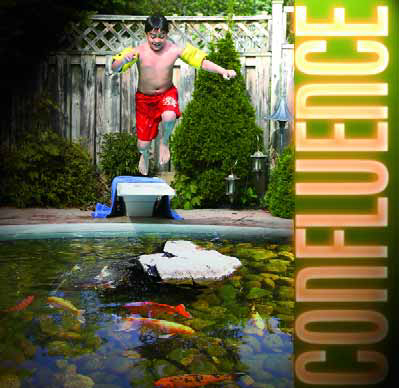

I've been using the word "confluence" a lot lately - so often, in fact, that I decided to look it up to be sure that I wasn't misusing it in some way. According to Webster, the first definition of confluence is "a flowing together of two or more streams," with a second meaning of "a gathering, flowing, or meeting together at one juncture or point." To me, it's a perfect word to describe a trend that's redefining the watershaping industries - that is, a growing confluence between the pool/spa and pond/stream industries. Coming from the pool/spa side of the discussion, I can recall a time not very long ago when ponds and streams were only rarely if ever considered by anyone in my business. What could pools and spas possibly have in common with