style

What’s the use of knowing about history? For many of us, the answer to that question seems so obvious that it comes as a shock to find out just how many people in the watershaping and landscape fields don’t grasp the all-encompassing significance of our collective past – but it shouldn’t. Using my own career as an example – and even though I now spend a considerable amount of my time teaching professionals and university students all about art and architectural history – I confess that I waltzed through more than a few early years as an aspiring landscape architect and watershaper in blissful ignorance of

Many great artists are best known for working in identifiable genres, styles or modes or with specific materials, themes or some other defining detail. From Picasso’s cubist abstractions to Mozart’s cascading melodies or Rodin’s bronzes to Frank Gehry’s sweeping architectural forms, geniuses of all stripes are in one way or another known for qualities that are distinctly theirs. The same holds true for many watershapers, especially those working at the top of the field. While many of us (myself included) cross the lines that divide distinctive modes, styles and genres, even the most free-spirited among us can be

It's rare in our fast-paced world when you get the chance to work closely with clients over an extended period of time – and in this case we took full advantage of the opportunity: All the way through the evolution of the project, the couple gave me voluminous information about what they wanted and enabled me not only to understand and deliver what they were after, but also allowed me in many instances to exceed their expectations. I had worked with him before on

I like to tell people that I have the greatest job in the world. It's true, and whenever I start working with a new client, I feel like a kid in a candy store. Look at it this way: As a watershaper, I get paid to use my ideas, experience, imagination and creativity to make my clients' dreams come true. Essentially, we're big kids playing with very big toys, and clients respond to our enthusiasm in a big way. And the best thing about it is that exterior designs are like fingerprints: Each one is different; every client has his or her own set of priorities; and every property calls for a

I like to tell people that I have the greatest job in the world. It's true, and whenever I start working with a new client, I feel like a kid in a candy store. Look at it this way: As a watershaper, I get paid to use my ideas, experience, imagination and creativity to make my clients' dreams come true. Essentially, we're big kids playing with very big toys, and clients respond to our enthusiasm in a big way. And the best thing about it is that exterior designs are like fingerprints: Each one is different; every client has his or her own set of priorities; and every property calls for a

Recently, much has been written and discussed in our local Los Angeles media - newspapers, magazines, television - about an influx of architectural styles to our area that "just don't fit in" and are generally thought of as being a blight on our collective landscape. This isn't anything new, of course. I recall similar dustups in the 1970s and '80s when the stylistic serenity of old, established neighborhoods was being disrupted by the insertion

Recently, much has been written and discussed in our local Los Angeles media - newspapers, magazines, television - about an influx of architectural styles to our area that "just don't fit in" and are generally thought of as being a blight on our collective landscape. This isn't anything new, of course. I recall similar dustups in the 1970s and '80s when the stylistic serenity of old, established neighborhoods was being disrupted by the insertion

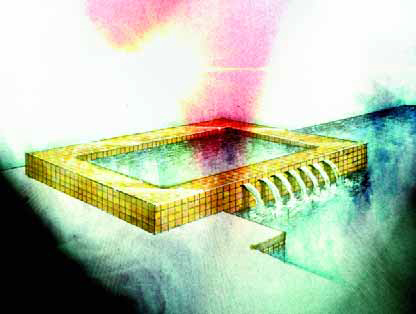

Last time, I described (at great length, as you may have noticed) what happens in the time between my initial phone conversation with clients and a point just ahead of my formal presentation of a design. It's an involved process that uses all of the information I've gleaned from my clients about what they want, what they think they need and what they ultimately expect to have in their backyard environments. It's about understanding the underlying circumstances, deciding what should be done and, finally, assembling all of that insight into a

Last time, I described (at great length, as you may have noticed) what happens in the time between my initial phone conversation with clients and a point just ahead of my formal presentation of a design. It's an involved process that uses all of the information I've gleaned from my clients about what they want, what they think they need and what they ultimately expect to have in their backyard environments. It's about understanding the underlying circumstances, deciding what should be done and, finally, assembling all of that insight into a

If there's a constant in watershape and landscape design and construction, it's that clients are almost invariably different from one another. Through years of watching how others approach these singularities, we've seen some designers (and builders) who are so set in their ways that they limit what they're willing to provide. Indeed, there even seems to be a bias in the industry at large toward elevating those designers who have a "trademark style." In our company's case, however, repetition of styles and features is not something that gets us going: Rather, we find it much more challenging and interesting to approach each project with fresh eyes and a genuine curiosity about our clients' dreams. To that end, our approach at Verdant Custom Outdoors (San Diego, Calif.) is all about understanding our clients and avoiding any preconceptions about what we think they might want. That in mind, we deliberately approach all clients and projects with a desire to meet individualized needs - a practice that has required us to become totally adaptable when it comes to both design and construction. To be sure, this approach adds a layer of complexity to what we do in that we start from scratch with every project. Our process requires a great deal of research, but as we see it, it's always been an investment of time and resources that constantly