paths

‘Whenever I receive a call for an initial meeting about a potential project,’ began Stephanie Rose in her Natural Companions column of May 2003, ‘I always envision – before the client ever opens his or her mouth – that I will be adorning a multi-acre estate with a classic garden that will someday be written about in books and examined by

"No matter how sophisticated you may be, a large granite mountain cannot be denied - it speaks in silence to the very core of your being." - Ansel Adams The man considered by many to be the father of American landscape architecture often referred to himself as a "garden maker," a self-description by Fletcher Steele that influenced me greatly when I first saw it in a book about him in 1990. When I think of the word "making" on its own, I see images of human hands crafting cherished artifacts or offerings, while the word "garden" conjures a host of images from Eden to Shangri-La. Taken together, however, the words evoke even more powerful images of the deliberate shaping of places of great beauty and serene repose - an apt definition for any landscape professional. When I borrowed those

Watershaping advanced by leaps and bounds from 1999 through 2004 – a journey of artistry…

Built to function and compete in an era when marketing matters for healthcare facilities, the McKay-Dee Hospital Center was designed to create a soothing, supportive, healing environment for patients, visitors and staff - so much so that the center looks more like a resort hotel than a medical institution. The architecture is open and soaring, offering sweeping views from interior spaces set up for comfort and restfulness. Designed by Jeff Stouffler of HKS Architects of Dallas, the structure is organized around a four-story atrium that runs the length of the building, offering clear lines of sight not only to distant mountain and valley views, but also to nearby landscapes graced with winding paths and beautiful watershapes. The opening of the 690,000-square-foot facility on March 25, 2002, was accompanied by great public fanfare. As people in the community have embraced and begun to seek care there, it's been a point of pride for us at Bratt Water Features to know that the beautiful curving lake that wraps around the exterior of the gleaming building is one of the things people see, enjoy and appreciate the most. BROAD SCOPE Our job was to build all of watershapes, including seven small fountains and the big lake system, based on designs prepared by Waterscape Consultants of Houston and by landscape architect James Burnett, also of Houston. As bidders on the installation contract in 1999, we had the advantage of being a local firm - but we also brought extensive experience with large-scale public waterfeatures to the table. And this project was big. As far as anyone on the design team knows, this is the largest waterfeature/fountain complex ever built in the state of Utah. We refer affectionately to the feature as "Bullwinkle" because, when seen from overhead, its oddly symmetrical free-form shape casts a silhouette resembling the cartoon moose's head and antlers. The antlers wrap around the footprint of the west end of the building, with the nose stretching away from hospital to create a broad lake with a towering geyser at the far end. The 175-foot-wide, 500-foot-long watershape features a 170-foot-long waterfall between the antlers and the crown of Bullwinkle's head that faces an outdoor pavilion/eating area served by an indoor café. The water falls four feet into a teardrop-shaped lower pond that serves as a catch basin - and which turned out to be critical to

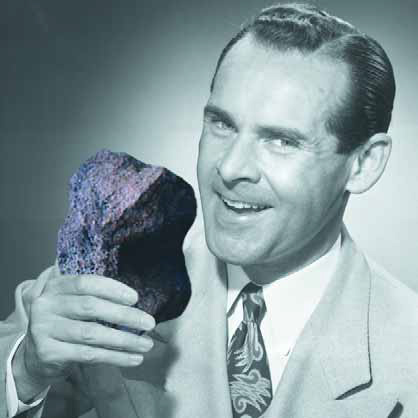

Rocks are, in my opinion, among the most versatile of all elements that can be added to landscape designs. As was discussed in my last column, they can be used to add texture or dimension or retain soil; they can also be used to add background or hide eyesores, and there are myriad other uses creative designers can find for them. Of course, different design styles call for different uses of rocks, stones and pebbles. An Asian garden, for example, might use them to simulate or represent water or mountains in a landscape, while the very same stones used in a cottage or natural setting might serve no purpose beyond providing a place to sit or a focal point that

The process of designing a watershape or garden usually requires the designer to answer a number of questions - the vast majority of them having to do with seeing the water and the landscape. Indeed, from considerations of color and scale to managing views and ensuring visual interest within the space, much of the designer's skill is ultimately experienced by clients and visitors with their eyes. But what if your client is blind or wheelchair-bound or both? How do you design for them? What colors do you use in your planting design? Would you even care about color? How will they move through the space and what experiences will await them? What would be the most important sensory evocation - sound, fragrance or texture? These are the sorts of special questions we asked ourselves after being approached by clients who had the desire to create a sensory garden for visually impaired and physically handicapped people. The experience shed a whole new light on the power of non-visual aesthetics and prompted me to