Travelogues & History

Whenever I visit the area with any time to myself, I enjoy visiting the Art Institute of Chicago. Not only does the museum host a collection of artwork expansive enough to include Renaissance masters as well as cutting-edge Modernists, but it also has what may be the best museum shop I've ever encountered.

It'd be well worth the visit even if it didn't also have a wonderful waterfeature - the Fountain of the Great Lakes - on its west side.

I'm a sucker for fountains that make me think not only about how they work but also what they mean, and in this case the interpretation of the way the Great Lakes flow and interrelate leads to a few moments of interested reflection. It's not exactly literal, nor is it very complicated: It's just a charming an allegorical representation of five vast, interconnected lakes that contain more than a fifth of the world's fresh water.

I find it amusing that the fountain was controversial in its day. Some were upset because the imagery wasn't quite literal enough. Sure, if you're visualizing a map of the lakes it's a bit difficult to read the relationships of the five figures as a clear representation of the system, but that seems trivial.

And then there were objections because there's a certain amount of metallic breast on display; that, too, seems trivial in such a classical set of forms. (You have to wonder if, back in 1913, those same prudes ran around putting their version of sticky-notes all over any Rubens painting the museum might have been fortunate enough to acquire or borrow.)

Personally, my only complaint is that the fountain isn't where it was originally placed: In 1963, it was moved from a venue of much greater prominence to its current spot adjacent to what was then a new wing that had been added to the museum complex. The positioning isn't terrible, but I don't like the reflecting pool/fountain that now shoots jets of water up into the space: The big sculpture works better on its own!

As defects go, however, that's an easy one to ignore. So when you visit the Art Institute and its great museum shop, take a few extra steps and visit a wonderful fountain that tells a nice little story about the region and its heritage.

As a garden designer, I've often heard about wonderful English gardens, historic British designers and specific design styles that have radiated from England through the years. I've studied books, seen wonderful profiles in magazines and searched the web for photographs and descriptions, but in recent years, the modern miracles of frequent-flier miles and house swapping have enabled me to experience these truly marvelous gardens for myself. My family and I, in fact, have visited England ten times since our first trip there in 1999. Each trip has given me the opportunity to visit amazing and inspiring gardens in different areas of the country - an education in design that I have fully integrated into my garden-design practice with Blue Hill Design in northern California. For their part, the English people are very welcoming - and especially, it seems, to gardeners: Gardening hosts on television are major celebrities, garden shows draw enormous crowds in a country where everyone

Our early-summer trip to Yellowstone National Park was a revelation to me, pure and simple. As I related in my Travelogue for July 22 (click here), the thing that occurred to me is that the inspiration at Yellowstone comes less from

For most of my life, I've been lucky to live within easy driving distance of a bunch of great national parks. Yosemite, Sequoia, Joshua Tree - the names alone flood my mind with memories of towering waterfalls, raging rivers, incredible landscapes, amazing rock formations and campfires that couldn't quite keep the cold at bay. In all my visits through the years, I've seen these "neighborhood" parks as naturalistic-design laboratories, as settings in which careful observation influences the work, fills the spirit and send watershapers back to the drawing board with all sorts of general ideas that might be of use down the line. Conceptual and visual treats, in other words - the stuff of inspiration. Last month, my wife and I ranged a bit farther afield than usual, hopping a plane to visit Yellowstone National Park. I have to say that the experience completely altered my sense of what a "naturalistic-design laboratory" might be. In this one park, I saw more

I've been writing these Travelogues once or twice a month since 2011, and a request from a reader for information about a particularly famous watershape revealed a significant gap in our information base: To my astonishment, I recognized I'd never written about the Fountains of Bellagio, which is a bit embarrassing when you consider it's one of my all-time favorites.

I saw it for the first time while attending the Aqua Show more than a decade ago. I was staying down the street at the Luxor (accommodations, I must say, not quite up to the Bellagio's standard); after returning from an excessively fine dinner with some Genesis 3 friends, I decided a long walk would do me good.

I reached the Bellagio at about 10 pm without too many preconceptions: I'd heard about the place, of course, and had seen a couple photos, but I wasn't prepared for what I found.

I don't know how long I stood at the railing, moving from spot to spot to take in the scene from as many angles as I could, but I know it must have been at least an hour. The whole time, I kept thinking, "This is why I love what I do." The display was simply sublime, an experience that still makes me feel good about how much energy I've put into the advancement of watershaping as an art form.

I've been back at that same railing many more times through the years, loving every minute of it. What particularly impresses me now is watching the sheer joy in the faces of so many of the people alongside me: There are lots of cool watershapes in the world, but very few of them are transcendent enough to become communal celebrations the way this fountain does.

The Fountains of Bellagio are, of course, the work of the designers and builders at WET Design (Sun Valley, Calif.), and I've always considered this project to be among the greatest expressions of the watershaping arts in the history of the planet. For me, in fact, it's the first among the Seven Wonders of the Modern World (no matter what the other six might be). Other projects have come along to rival them, but these fountains deserve all the respect that comes with real trailblazing.

There's a lot to like about the original, including the excellent choreography, the thoughtful musical selections and the brilliant lighting program. My personal favorite detail, however, goes unseen and largely unheralded: It's the fact that the water comes from a well that had been used to irrigate a golf course abandoned when the Bellagio was built. Even with the jetting water and all that splashing in the middle of a desert, the fountains consume less water than the turf always did.

I do, however, have a quick, sad story to tell. My wife is a schoolteacher, and getting her to travel with me to trade show has been a rare treat. I persuaded her to come with me to Las Vegas some years ago because I knew that I was to be named Pig #8 or #9 by Genesis 3 and I wanted her to witness the ceremony. Afterwards, I took her to the Bellagio to see the fountain: It was a cold, blustery night, and when we finally reached the railing, we saw the basin covered in whitecaps and learned that the water show had been cancelled for the night.

I don't know if I'll have the chance to try again at sharing the Fountains of Bellagio with her, but for the rest of you, here's my edict: It's a trip worth making, an experience well worth sharing and a special event that makes going to Las Vegas a pleasure, every time.

For a unique behind-the-scenes perspective and some history, click here. To see one of the best possible combinations of music and fountain choreography, click here - and please stick with it to witness the aquatically pyrotechnic crescendo!

'For years,' wrote David Tisherman in his Details column in the June 2005 issue of the magazine, 'people have asked me where I get my ideas - pools raised out of the ground, the small spillways, the drain details, the modular deck treatments, the color usage and the use of reflection, to name just a few. "Through my design education" is the short answer, of course, but I can get more specific if we take a look at

I lived in Cleveland at a point when I was too young to remember a thing about the place: We moved there when I was ten months old and stayed for about a year. But I've always considered it as one of my several "home towns" and have been back there twice since we moved away in 1957, both times on business - and both times before I became involved with watershaping.

Just the same, as an art history enthusiast and fan of impressive sculpture, I had my breath taken away by "The Fountain of Eternal Life." Dedicated in 1964, it was designed and executed by Marshall Fredericks, a resident of Michigan but a 1930 graduate of the Cleveland School of Art. The fountain serves as an inspiring memorial to residents of the city who died in conflicts reaching all the way back to the Spanish-American War.

It wasn't that inclusive when I first saw it in 1978 and again a few years later: Originally, the bronze plates surrounding the rim of the fountain memorialized only casualties of World War II and the Korean War. This recognition has since been expanded on a couple of occasions to include all Clevelanders who've died in defense of their country in the span from 1899 to, so far, 2014.

The testimony of sacrifice as witnessed by the names is moving, but the sculptures within the fountain are quietly but utterly inspirational. The central figure, which rises high above the basin and stands on a representation of the earth engulfed in flames, signifies the spirit of mankind rising above the destruction of war and reaching hopefully for a new and enduring comprehension of the value of life. The four granite sculptures at the base represent the world's civilizations and express a general desire for a global future free of war.

I haven't been back to Cleveland in many years, but I know that, when and if I return, one of my first stops will involve revisiting this fountain.

It was meaningful and impressive enough when I first saw it, but the continued addition of names is a reminder that, for all of our aspirations, for all of our sacrifices as friends and relations of wars' casualties, we can't seem to realize Fredericks' idealistic dream.

It's a humbling space - a graceful, monumental sculpture and a gracious, inspirational reminder that we are all in this together.

To see a brief video of the fountain in action, click here. The narration is a bit, well, distracting, so turn the sound down and watch: The images are just fine.

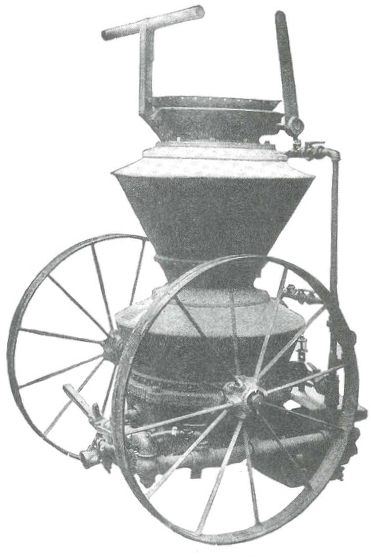

From mine shafts to subway tunnels, from fountains to swimming pools, shotcrete has long been the preferred material of construction for major projects worldwide. This process, which involves the spraying of concrete material at a high velocity onto a receiving surface to achieve compaction, offers substantial advantages over alternative approaches with respect to durability, versatility, integrity and sustainability. This has been the case ever since the technique was invented at the turn of the 20th century, yet only now are watershapers - professionals who have made concrete such a crucial part of their livelihoods - truly coming to understand and appreciate shotcrete for what it is. In this three-part series, we'll start with the story of shotcrete's origins - a tale of insight, ingenuity and entrepreneurship. Then we'll trace

A few weeks back, I paid a visit to Santa Rosa, a city in the heart of California's Sonoma County wine appellation. I wasn't there to taste wine, surprising as that may seem. Instead, I went to visit with Jim Wilder, a regular WaterShapes contributor and fountain specialist who's spent his career working up and down the valley, quite often