Book & Media Reviews

As watershape environments become increasingly integrated with homes and overall exterior spaces, increasing numbers of our clients are asking us for associated structures - everything from outdoor kitchens and dining areas to arbors, cabanas and pool houses. In my case, just about every single design I tackle includes one or more of these features. What this means is that we watershapers are effectively being drawn into the world of architecture. While we may not ultimately design or build these structures, at the very least we need to be familiar enough with their ins and outs that we can talk about them intelligently in the context of a given project. I've picked up a lot of basic knowledge through experience and close observation, but I recently decided to seek out a formal reference that would help me give definitive answers to a wide range of these questions, some as simple as inquiries about how much

By now, we all know that pools and certain other watershape forms have been around since ancient times. It's my strong suspicion, however, that most of us who design and build backyard swimming pools today would fail a pop quiz about those who pioneered the 20th-century genre of pool design. I was among you in not knowing, for instance, about the seminal role played in this arena by a man named Garrett Eckbo - this despite the fact that he's one of the icons of landscape architecture. As a founding member of (and the "E" in) EDAW, Eckbo was responsible for some of the grandest public spaces in the United States. He was also, it seems, an innovator in residential garden and pool design who put his stamp on just about every basic pool form we use today. I picked up this knowledge from a book by Marc Treib and Dorothy Imbert called Garrett Eckbo: Modern Landscapes for Living (University of California Press, 1997). The 190-page volume covers the major career phases of a California-based designer and longtime professor who

By now, we all know that pools and certain other watershape forms have been around since ancient times. It's my strong suspicion, however, that most of us who design and build backyard swimming pools today would fail a pop quiz about those who pioneered the 20th-century genre of pool design. I was among you in not knowing, for instance, about the seminal role played in this arena by a man named Garrett Eckbo - this despite the fact that he's one of the icons of landscape architecture. As a founding member of (and the "E" in) EDAW, Eckbo was responsible for some of the grandest public spaces in the United States. He was also, it seems, an innovator in residential garden and pool design who put his stamp on just about every basic pool form we use today. I picked up this knowledge from a book by Marc Treib and Dorothy Imbert called Garrett Eckbo: Modern Landscapes for Living (University of California Press, 1997). The 190-page volume covers the major career phases of a California-based designer and longtime professor who

For years now, we've all heard that consideration of a site and its surrounding environment is one of the things that separates the average from the truly great projects. For my part, as I've grown as a watershape designer, I've found this simple concept carrying more and more weight in my work. With that site-driven value system somewhere in mind, I recently came across two books that provide some of the most compelling examples of this approach I've ever seen. It all started when I read a newspaper article about architect Antoine Predock, the 2006 recipient of the

For years now, we've all heard that consideration of a site and its surrounding environment is one of the things that separates the average from the truly great projects. For my part, as I've grown as a watershape designer, I've found this simple concept carrying more and more weight in my work. With that site-driven value system somewhere in mind, I recently came across two books that provide some of the most compelling examples of this approach I've ever seen. It all started when I read a newspaper article about architect Antoine Predock, the 2006 recipient of the

When it comes to design in the watershaping industry, I see all of us who creatively put pencils to paper as being in states of transition - particularly where I live in the pool/spa realm, where design has traditionally been used as a sales tool and charging for design work was largely unheard of as a service above and beyond construction. All that is changing - and for the better, I think. But with more and more of us gravitating in the direction of professional design consulting either within companies or on our own, what's to guide us as we reach toward that goal? A book I've just read may be a big help: Andrew Pressman's Curing the Fountainhead Ache: How Architects and Their Clients Communicate (Sterling Publishing Co., 2006) has led me to recognize that good design is mostly about establishing effective dialogue with clients. Indeed, he has convinced me that the way I talk to my clients - and, as important, how well I listen to what they have to say in return - has everything to do with

When it comes to design in the watershaping industry, I see all of us who creatively put pencils to paper as being in states of transition - particularly where I live in the pool/spa realm, where design has traditionally been used as a sales tool and charging for design work was largely unheard of as a service above and beyond construction. All that is changing - and for the better, I think. But with more and more of us gravitating in the direction of professional design consulting either within companies or on our own, what's to guide us as we reach toward that goal? A book I've just read may be a big help: Andrew Pressman's Curing the Fountainhead Ache: How Architects and Their Clients Communicate (Sterling Publishing Co., 2006) has led me to recognize that good design is mostly about establishing effective dialogue with clients. Indeed, he has convinced me that the way I talk to my clients - and, as important, how well I listen to what they have to say in return - has everything to do with

As an extension of my landshaping work in Iowa, I currently serve on a committee formed not long ago by the Johnson County Heritage Trust. Our mission is simple but immense: to preserve as much of the natural environment as possible. The committee was formed in response to development of a new subdivision in a high-quality oak/hickory forest in which relatively few invasive species had gained footholds. Our immediate task was to compile a list of acceptable plants for this community as well a list for the whole county. Of course, this story is much larger than

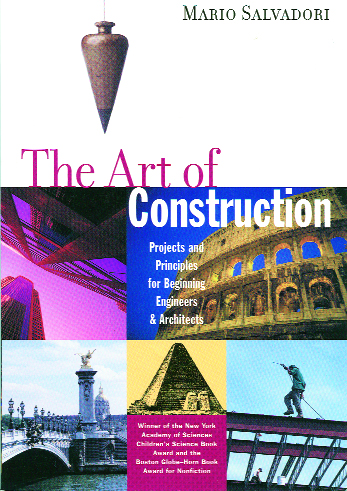

Most watershapers know that the work we do requires knowledge across a wide range of disciplines - a cluster of skills that includes, among others, geology, materials science, structural engineering, construction techniques, hydraulics, architecture, art history, color theory, drafting and more. As jacks of all trades, we don't really need to be "expert" on all of these fronts, but without a working knowledge of the technical and aesthetic disciplines involved in creating quality work, it's difficult to ensure the success of any given project. There's no question that some of us are better at certain disciplines than others, and it's up to us to recognize our strengths and weaknesses and fill in the gaps of our understanding as best we can. When it comes to structural engineering, for example, few of us qualify as bona fide engineers: That takes years of schooling and rigorous licensing processes. But almost all of us work with precise structural designs that are specific to the vessels and associated structures we design and/or build. In other words, we may not be engineers, but we sure as heck need to

Most watershapers know that the work we do requires knowledge across a wide range of disciplines - a cluster of skills that includes, among others, geology, materials science, structural engineering, construction techniques, hydraulics, architecture, art history, color theory, drafting and more. As jacks of all trades, we don't really need to be "expert" on all of these fronts, but without a working knowledge of the technical and aesthetic disciplines involved in creating quality work, it's difficult to ensure the success of any given project. There's no question that some of us are better at certain disciplines than others, and it's up to us to recognize our strengths and weaknesses and fill in the gaps of our understanding as best we can. When it comes to structural engineering, for example, few of us qualify as bona fide engineers: That takes years of schooling and rigorous licensing processes. But almost all of us work with precise structural designs that are specific to the vessels and associated structures we design and/or build. In other words, we may not be engineers, but we sure as heck need to