Working the Nitrogen Cycle

If you’re responsible for keeping up a watergarden, you probably know how important including a good balance of aquatic plants and fish is to sustaining a healthy ecosystem. You also likely know that some basic maintenance is important, too – including chores such as removing decaying leaves in the fall and sprucing up the pond in the spring.

This is all great, but many people who accept these responsibilities are just doing as they’ve been instructed without understanding why these tasks are so critical to maintaining a pond’s health, water quality and clarity. Happily, you don’t need a degree in environmental science to get that fuller picture: There’s a simple natural cycle – the nitrogen cycle – that governs what you’re doing and determines the ultimate health of the pond you’re managing.

Indeed, the nitrogen cycle is certainly one of the most important of all natural cycles because it’s the building block of all organic life forms. Knowing a bit more about how it works will dispel lots of mysteries of pondkeeping and go a long way toward helping you understand the processes that happen in a pond and deal with questions that come up in the course of managing fish, plants and the overall performance of the environments they occupy.

A NATURAL PROCESS

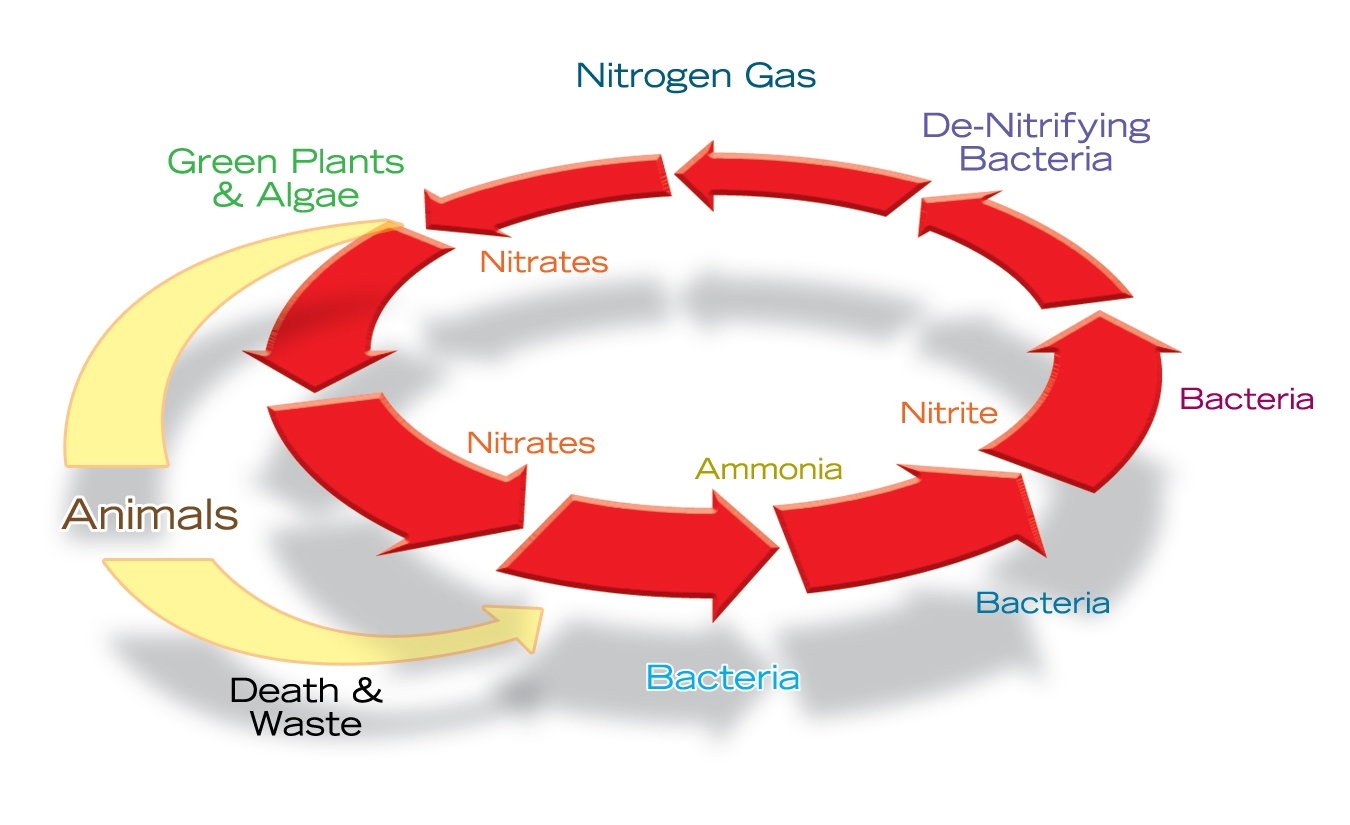

The nitrogen cycle – or, more formally, the nitrification process – is a biological phenomenon in which ammonia (NH3) first becomes nitrite (NO2) and then nitrate (NO3). The amazing thing is that this process can start at multiple points and has the ability to go either backward or forward, allowing a variety of complex biological processes to occur.

That can be a head scratcher, so I’ll try here to illustrate the basics in a way that helps you visualize what’s happening. But let’s start with a caution: As with so many big concepts, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. And also a hope: That same small amount of knowledge, properly and wisely applied, goes a very long way.

So what I’m saying is that I hope you won’t be one of those pond owners or maintainers who start worrying about the many forms of nitrogen that might be present in the pond and start altering portions of the water’s chemistry in hopes of creating a perfect aquatic environment or ecosystem. That’s not the right path.

What you really want to do is set chemical manipulation aside and focus instead on approaching a properly designed and built pond, cleaning the debris out of the skimmer on a regular basis, adding bacteria as recommended and trimming away dead aquatic plants: If you do so, chances are better than good that you’ll have no problems and will encourage the nitrogen cycle to hum along the way it wants to, in perfect balance.

NITRATE PRODUCTION

Basic nitrogen gas (N2) makes up approximately 78 percent of our atmosphere – but in this form the element is inert and cannot be used by plants or animals. It makes its way into ponds mostly via rainwater, and even with steady rainfall it takes a lot of energy to convert it to a form usable by plants. What isn’t consumed simply returns to the atmosphere through evaporation of the pond’s water.

Some of the introduced nitrogen reacts with the water’s hydrogen to form ammonia, a compound that, in and of itself, isn’t beneficial to plants or fish. This is where the way the pond is put together comes into play: The large area represented by the surface of the biological filter media as well as by the rocks and gravel inside the pond allows for colonization by beneficial bacteria that drive the nitrification process, changing ammonia first to the less toxic nitrites and also to the usable nitrates.

Some of the introduced nitrogen reacts with the water’s hydrogen to form ammonia, a compound that, in and of itself, isn’t beneficial to plants or fish. This is where the way the pond is put together comes into play: The large area represented by the surface of the biological filter media as well as by the rocks and gravel inside the pond allows for colonization by beneficial bacteria that drive the nitrification process, changing ammonia first to the less toxic nitrites and also to the usable nitrates.

This is why regular addition of beneficial bacteria is so strongly recommended by pond experts: It’s all about keeping ammonia in check and converting it to other compounds.

Plants play a big role here, too. Nitrate is either absorbed by aquatic plants or, in anaerobic conditions, goes through a process of denitrification in which nitrate becomes nitrogen gas once again. (Although it is uncommon in ornamental ponds, if unusually high nitrate levels are detected, it can also be removed by small, frequent water changes.)

Nitrates can also be added to a pond by way of atmospheric fixation. This occurs during lightning storms, when strong electrical charges break down nitrogen gas and allow it to combine readily with oxygen to form nitrogen oxide in rainwater. This is why lawns green up following lightning storms: Not only is the grass receiving water, but it’s also getting a dose of nitrate fertilizer.

Lightning storms can also have an unfortunate greening effect on ponds – hence the recommendation to add some liquid bacteria to the water after a storm to counteract the sudden influx of nutrients.

AMMONIA AT WORK

Another contributor to high nitrogen levels in pond water is the fertilizer used in landscapes around the water. During a heavy rain or in the event of excessive irrigation, fertilizer (mostly made of ammonia and phosphorus) frequently washes into a pond and can cause algae blooms and other water-quality problems that can kill fish and invertebrates.

Another ammonia source is organic debris, including leaves, lawn clippings and dead fish or insects. These materials break down, forming ammonia as a byproduct and triggering another denitrification process. This is why regular clearing of skimmer baskets is so important – and why, if the pond is subjected to heavy leaf fall in the autumn, the use of protective netting to keep debris away from the water is recommended.

Yet another ammonia source is the fish that inhabit most ponds. When those fish are fed, the result is a combination of waste and uneaten food – both of which contribute to ammonia levels in ponds. This is why fish shouldn’t be fed more than they can consume in a few minutes. It’s also why feeding them high-quality, probiotic-containing foods is a good idea: These foods help fish derive more energy from less food, reducing waste and actually helping further by breaking down waste and other organics normally found in pond environments.

The key to balancing out all of this ammonia generation is good oxygenation and aeration. This is why so many ponds are designed with churning cascades and waterfalls: They introduce oxygen that is essential both to fish survival as well as to efficient nitrification.

That’s the long and short of the nitrogen-cycle story – enough information to help you understand the importance of some of the advice you should have received about maintaining a pond, and more than enough insight to help you see to the basic nitrogen-related needs of fish and plants!

Ed Beaulieu is director of contractor development and field research for Aquascape, Inc., St. Charles, Ill. For more information, visit www.aquascapeinc.com.