Why Colored Plaster Fades

Having a beautiful pool with a colored surface, especially one with a quartz or pebble plaster finish, is a popular choice among pool owners, and understandably so. The color adds ambiance to the setting and can make the water wonderfully attractive and inviting. That’s why pool owners are willing to pay extra to have that special color enhance their water andby extension the entire backyard.

With that investment in aesthetics, consumers rightfully expect the attractive appearance they’ve paid for to last a long time. In turn, builders, remodelers, and plasterers are motivated to provide colorfast surfaces that endure the dynamic swimming pool environment. Unfortunately, as we all know, that’s not always the case – colors do sometimes fade.

Because the interior pool surface is such a dominating visual element, it must be disappointing for everyone involved on those occasions when they watch their pigmented, colored pools become unsightly with whitish blotches, streaks, or small spots. Later on, it must also be disappointing, if not more so, to learn that the cause of the unsightly problem was misdiagnosed, and worse, the remedial action taken to resolve that problem caused even more serious damage.

The good news is a dose of basic information goes along way in figuring out how to avoid the problem in the first place and remedy it when it does occur.

SHADES OF PALE

Colors fade for a handful of preventable reasons. First off, it is possible to scale or etch pigmented plaster surfaces with water that is out of balance. This is not new information and professionals in the pool industry are very familiar, or at least they should be, with these failures in maintenance and the resultant deposits or surface roughness. As is widely known, scale makes the surface turn white, and acid washing is often the remedy.

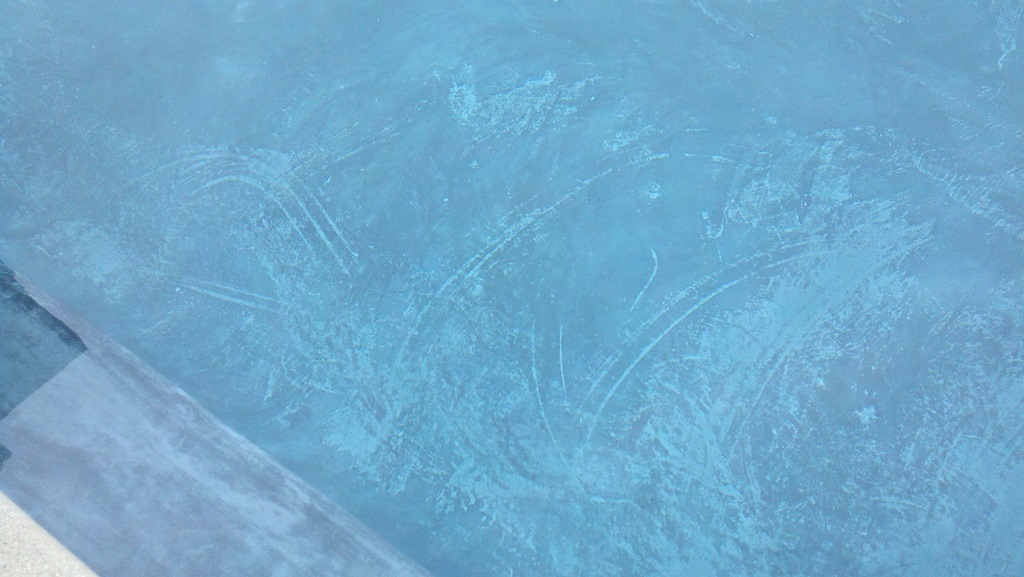

| A classic example of whitening due to porosity, which manifests as light streaks, spots and patches. |

It is also common to lighten colored plaster surfaces because of mistakes in material selections, placement, finishing and/or curing. Because changes in color resulting from these defects are also a lighter or whitish color, it is easy to mistakenly believe that the problem is calcium scaling, and that the pool water has been out-of-balance. Once you make that misdiagnosis, it’s then easy to mistakenly assume an acid wash is the best remedy. But when there’s no scale there to remove, that will only cause etching, it won’t fix the problem and will shorten the life of the plaster.

The whitening of colored plaster is caused by soluble calcium ions in the plaster dissolving and fleeing the scene into the pool water, the exact opposite mechanism that causes scale. When that dissolution occurs, it means the plaster surface is losing density and becoming porous. When porosity develops and increases, a whitening of color/pigmented plaster is a result, yet it usually remains very smooth.

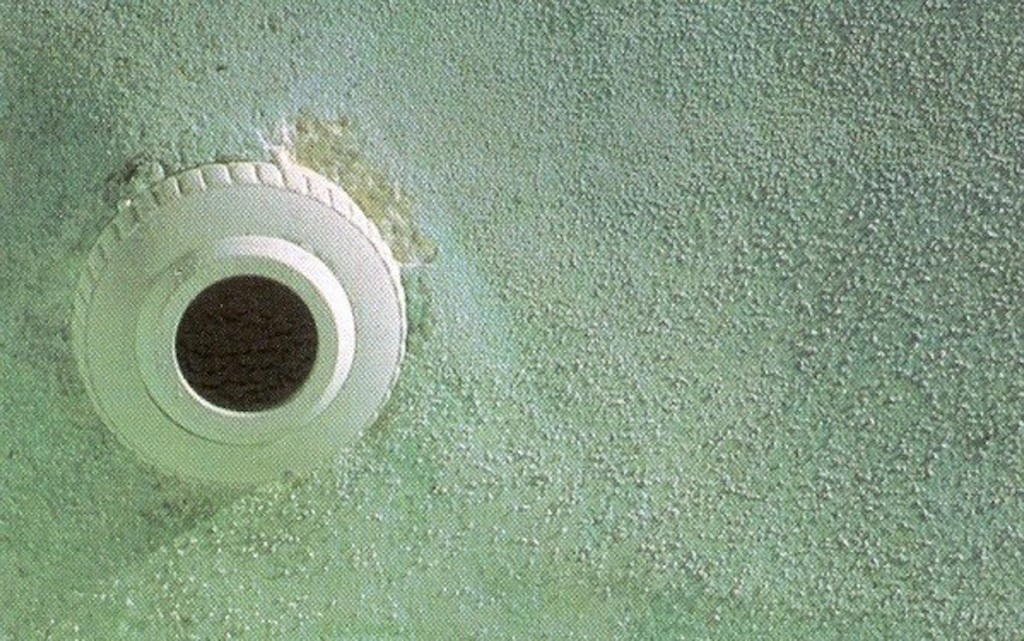

| Aggressive water could not have been the cause for this marred surface, as it would have created a more uniform effect. |

Porosity appears lighter because of the way it reflects more light than a non-porous surface. It’s closer in structure to liquid foam than it is to etching that occurs as a result of aggressive water chemistry. According to Dr. Boyd Clark, senior materials specialist with Construction Technology Labs, it’s the same reason that a head of foam is lighter than the beer; the foam is lighter in color because it throws off more light: “The fact that we have a spot, or a lightened area is due to the fact you have an increased porosity,” he says.

It’s helpful to note that even common white pool plaster can develop white spots and streaks that are whiter than the surrounding plaster because of increased porosity in those areas. There is a direct connection in how white and pigmented plaster develops color-shading changes. In effect, you have two opposite causes for what appears to be the same effect.

SCALE V. POROSITY

Calcium scaling, which is caused by out-of-balance water (an overly positive LSI value), usually deposits a uniform layer of calcium carbonate throughout a pool and whitens the entire pool, including fixtures. It is generally rough to the touch and can be easily removed by scraping or sanding with sandpaper.

| These coupons show examples of chlorine bleaching organic pigmented colors but leaving inorganic pigments untouched. |

On the other hand, if the whitish discoloration is smooth to the touch, manifests itself in streaks, blotches, or small spots, and if diluted acid does not quickly remove the white discoloration, then one should realize that the problem is probably not calcium carbonate scaling but a porous surface instead.

What leads to a porous surface? There are two relatively soluble components of hydrated (cured) cement/plaster. They are calcium hydroxide (a by-product of the cement/water reaction) and calcium chloride (if added to the mix). Calcium carbonate, a primary plaster constituent, is insoluble. Some people falsely assume that calcium hydroxide and calcium chloride can only be dissolved by aggressive pool water (negative LSI). In fact, both elements can be dissolved by balanced water and even positive LSI water. That means something other than poor water chemistry is the culprit for porosity developing and a whitening effect.

| The faded marks on this pool clearly show the effect of direct water-troweling on a black-colored plaster surface. |

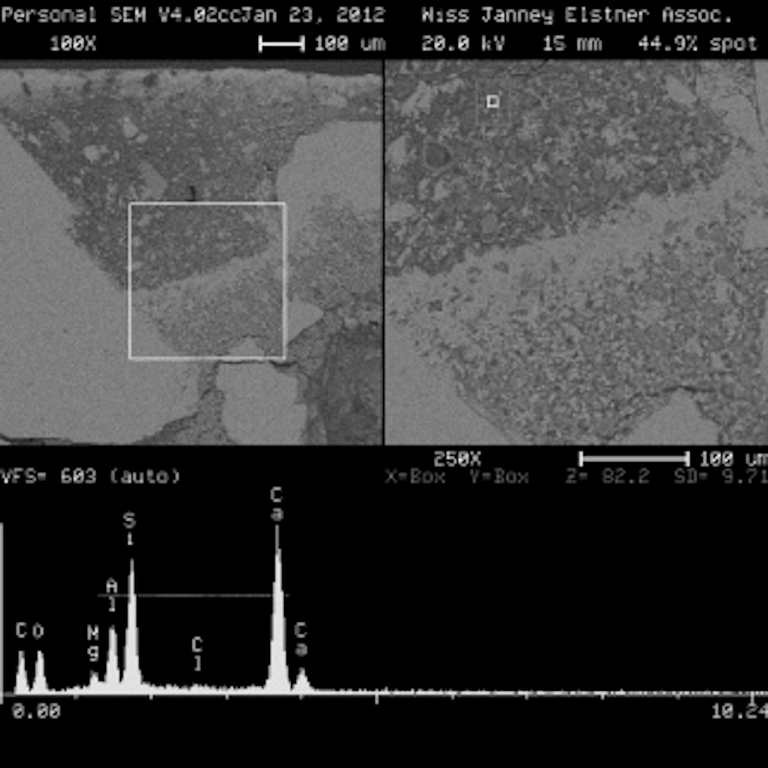

Given the above, the logical thing to consider for color problems is plaster quality. Together the authors are the principals of the onBalance research team, which began examining failed colored pools 20 years ago. Among many inquiries and studies over the years, we sent plaster samples to professional cement labs to perform scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis in search of a reason for plaster whitening.

We specifically asked the researchers at the labs to look for aggressive water effects, but they didn’t find any. Instead, the reports mostly implicated poor workmanship and materials as the reasons for the porosity that causes color loss and whitening.

The following were the plaster mistakes mentioned by the labs that are associated with whitening cause by porosity:

q A high amount of water added to the plaster mix that contributes to excessive shrinkage and porosity.

| This is what whitening due to scale looks like; it’s very rough and uniform, unlike when discoloration is caused by porosity, which is very smooth and splotchy. |

q An excessive amount of added calcium chloride, a hardening accelerator (often referred to as just “calcium” or “chloride”), which also contributes to shrinkage, porosity, and blotchiness.

q Applying large quantities of water to the surface while troweling, which increases porosity and color shading differences, while overly late hard troweling causes graying (mottling) of white plaster, or a darker color in pigmented plaster.

There’s no question that poor workmanship and materials can result in an overly porous cement/plaster surface, including excessive shrinkage cracks, which also turn noticeably white. Those defective plaster practices lead to excessive porous surfaces that allow water, whether it’s balanced or imbalanced, to penetrate and dissolve soluble plaster components from the surface. It is the increase in porosity that results in a whitening effect in those compromised areas.

Aggressive water does not necessarily cause micro-porosity. When aggressive water etches a plaster surface, it creates a rough, pitted and jagged surface without causing loss or changes, which is different from a surface micro-porosity.

QUALITY COLORED PLASTER

Within the cement/concrete industry, it is commonly known that producing a hard and dense cementitious surface is a major requirement to help ensure vivid and more consistent colors that last many years. A quality cement product can stand up to harsh conditions, such as aggressive water (the same as rain, which is very aggressive, on driveways or sidewalks).

| This close-up SEM imaged indicates that the plaster is porous and has lost calcium hydroxide, creating a porous surface. |

When a quality plaster finish is produced with good workmanship and materials, just like concrete, it helps prevent color pigment(s) and other soluble plaster material from dissolving out of the plaster.

Below are some good workmanship practices suggested by the Portland Cement Association to produce a hard, dense, and quality cementitious surface.

q Use low water content (water/cement ratio) for the plaster mix. Make the plaster mix as thick as reasonable for proper troweling. That helps to provide a denser (less porous), harder, and more durable plaster finish.

q Calcium chloride should not be added to colored plaster mixes. Pigment manufacturers recommend not adding calcium chloride as it can cause blotchiness. Also, tests have shown that about one-fourth of the added calcium chloride will dissolve out of plaster, thereby increasing porosity.

|

A Porous-Plaster Remedy An extreme acid treatment is often tried to restore the original color of the plaster. However, such acid treatments also etch the plaster and make the surface rough. That simply reduces the life span, and the pigment color may still fade away and turn whitish once again. A better alternative for removing a porous and whitened surface would be to sand/polish the plaster. That process removes the porous material and restores a hard, dense, and smooth surface. Unfortunately, when dealing with discolored pebble (exposed aggregate) finishes, sanding and polishing is virtually impossible. — K.S., Q.H. & D.L. |

q The application and troweling of the plaster surface should be well timed to compact the plaster material properly. Avoid overly late hard troweling and having to add lots of water to the surface to make it more pliable for troweling. The “water troweling” is a detrimental practice that severely weakens and creates undesirable porosity.

ANOTHER FACTOR

There’s another reason for color loss: some plasterers or suppliers use organic pigments in their plaster mixes. Organic pigments can be bleached by the presence of chlorine or other oxidizers, and even by the sun. It is recognized that organic pigments are cheaper than inorganic pigments, but they generally cannot withstand a swimming pool environment for long.

This bleaching action occurs even if the plaster workmanship is high quality. Some plaster mixes contain two pigment colors. If one is organic and becomes bleached, that color will simply disappear leaving the other non-bleachable pigment visible as the sole color.

Kim Skinner, Que Hales and Doug Latta are the founders of onBalance, and industry research group that for more than 20 years has focused on examining highly technical issues related to water chemistry, the materials science of cementitious surfaces and ways to prevent common problems.