When It Rains

The numbers are eye-popping: Just about one percent of all the water on Planet Earth exists as freshwater suitable for human consumption. And depending on where you live in the United States, anywhere from a quarter to almost half of that precious resource is used for irrigation.

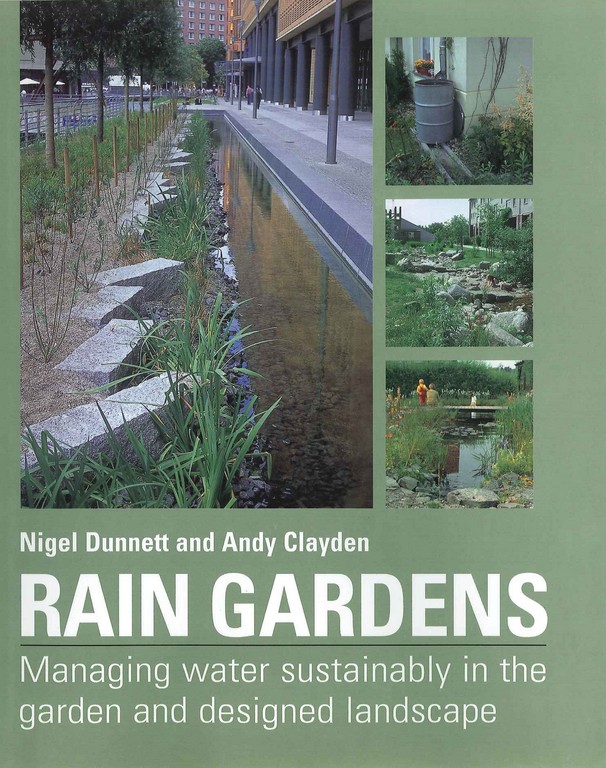

This is why it’s so important for those of us who design watershapes and exterior environments to consider options that minimize our use of potable water to maintain the landscape – and why I’m glad I picked up a copy of Rain Gardens by Nigel Gunnett and Andy Clayden (Timber Press, 2007): This 190-page text defines specific steps we can all take to replace municipal or well water with rainwater, capturing a gift from the skies and using it to sustain our landscapes.

As the authors point out, we live in a time when drought is becoming more and more prevalent: When the rains do come amid dry spells, it’s often in record-setting torrents that cause floods and property damage.

If homeowners established environments that captured a good portion of this sudden water rather than let it run rapidly to waste, two key issues would be affected in positive ways: The stored rainwater may be used in place of piped-in irrigation water, and the simple act of diverting the flow to storage relieves a measure of pressure on public drainage systems and helps keep them from being overwhelmed. At present, however, few of us create structures or hardscape elements that do anything more than send water to waste – and that, say the authors, is something we should change.

At the heart of their discussion of “rain gardens” is the concept of bioretention, the simple notion of using plant material to slow down and capture water. They offer various examples showing how water that would otherwise flow into drains can be channeled instead to fill retention ponds or flow into irrigation systems before percolating into the ground.

That sounds simple, but as Gunnett and Clayden point out, we need to think differently about how we organize surface flows and landscapes with these ideas in mind. The beauty of it all, they note, is that it costs very little to take this conceptual step – and the plain fact is that rain gardens can be wonderful.

The authors also observe that, where rain gardens aren’t possible or practical, you also have options in using rain barrels or cisterns to collect and store water for irrigation. They also discuss ways that gray water (that is, runoff from washing machines and showers and sinks) can be used for irrigation purposes, the caveat being that this is illegal in some parts of the country – a prohibition they hope will change before too much longer.

Two other big ideas they cover include the use of green rooftops to capture water (which has the added benefit of passing water through the biofiltration system represented by plant material) and the use of wetland areas to pre-treat water used in swimming pools.

Certainly, none of these ideas is new. Indeed, and as they point out, there are situations around the world where these strategies have been in place for decades. But now, as environmental concerns are becoming a greater part of mainstream thinking in the United States, it’s clear that these design options will be more in demand and become more commonplace.

As watershapers and landscape designers and architects, we all have everything to gain by ramping up our efforts to make better use of all available resources – and especially water. And there’s nothing wrong with making those spaces beautiful as well!

Mike Farley is a landscape architect with more than 20 years of experience and is currently a designer/project manager for Claffey Pools in Southlake, Texas. A graduate of Genesis 3’s Level I Design School, he holds a degree in landscape architecture from Texas Tech University and has worked as a watershaper in both California and Texas.