Restoring Waters Past

The history of modern swimming pools really dates back just a hundred years or so. Yes, there are examples of pools, baths and other watershapes from the distant past, but the swimming pool as we know it is something that truly emerged during the 20th Century, mostly after World War II. Before then, there were probably no more than 50,000 pools built in all of the United States – and most of those were seen as something quite special for their time.

Nowadays, we’re far enough into the development of “modern” swimming pools and other watershapes that a small number of “antique” pools have been declared historical landmarks, with those at Hearst Castle being perhaps the best examples among many. Some of these pools happen to have been built for the residences of famous people, while others were installed on commercial or institutional properties that are “historic” by virtue of having survived long enough to develop some sort of cultural and/or civic cachet within their communities.

In some cases, these venerable watershapes exemplify fine design and architecture; in others, it’s more about the celebrities who swam in them. Either way, some are protected as historic sites and others will be, yet the fact of the matter is that nobody really knows just how many of these rare pre-war structures have survived into the 21st Century.

Given their short history, the idea that swimming pools might require historic restoration is relatively new and has been a factor mostly during the past couple decades – a time in which our firm, Rowley International of Rancho Palos Verdes Estates, Calif., has been fortunate enough to participate in a variety of historic restorations of swimming pools across a range of settings and types.

Some of these projects have been among the most unusual and challenging we’ve ever tackled, including the one I’ll focus on here.

VAST IN SCOPE

Unless a pool has been listed on some registry of historic places, it’s difficult to define in precise terms exactly what is and isn’t historic when it comes to swimming pools. It’s so subjective, in fact, that what makes a pool “historic” to me is simply that some concerned group of people has declared it to be so.

Often times, these are civic groups seeking to preserve local culture and history. In other cases, it may be a particular institution or commercial property that has declared the historical value of a given facility on its own, usually for promotional purposes. The one constant for us in getting involved in these projects is that they are all different and that the work required to restore them will vary wildly.

There are always surprises, and the careful reworking of these structures offers a fascinating view of the way pools were built in years gone by.

For the most part, restoration work flows in distinct phases, often beginning with some sort of detailed feasibility study that is followed by design and bidding phases and, finally, the construction process. In some cases, these phases can take several years, because every step is carefully scrutinized by local historians and architectural historians as well as architects and designers who typically are drawn from top firms well-attuned to the special needs of historic buildings. These people tend to see restoration as an art form all its own.

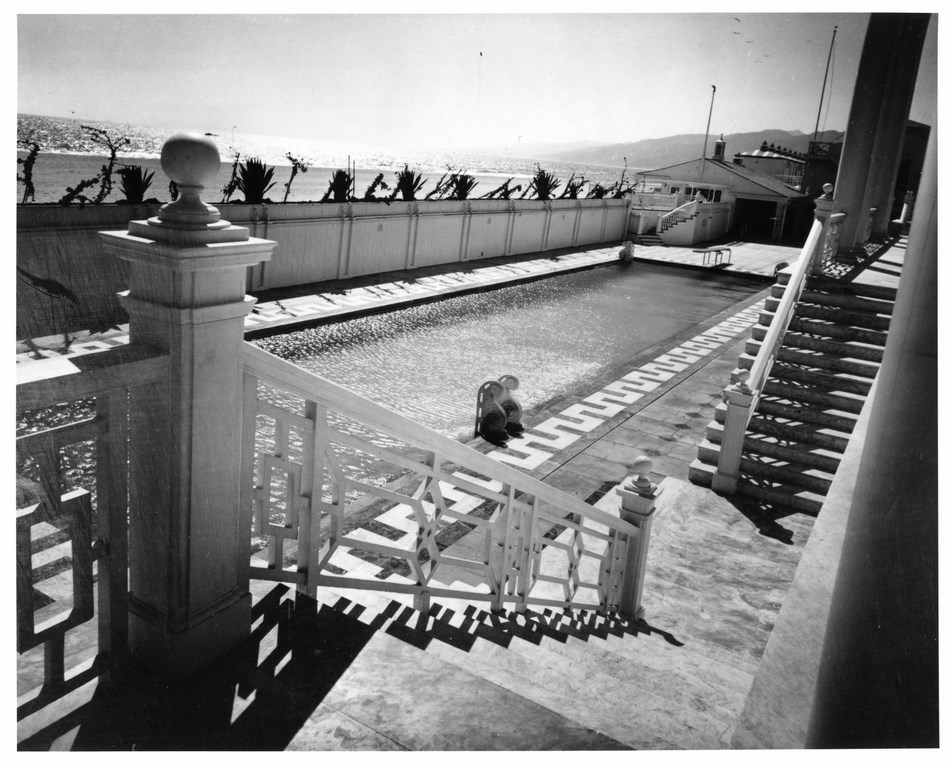

| The pool is currently covered by a huge plywood structure that was likely installed as a safety measure but has also been beneficial in forestalling additional damage to the pool’s interior finish. Even here, it’s possible to see that the decking, despite exposure to the seaside elements for more than 70 years, was and will again be magnificent. |

The processes stretch over a course of years for two primary reasons: First, every step to be taken on a historic site must be proposed, considered in painstaking detail and ultimately approved. This can get incredibly convoluted, because in many cases, measures that are appropriate from the restoration standpoint run diametrically counter to modern building and health department codes. What this means is that many project elements will be the products of spirited negotiations as ways are found to bend or create exceptions to closely followed rules.

How spirited can it get? Suffice it to say that we’ve learned through the years just how serious a business historic preservation can be.

The people who become involved in these projects tend to be committed, passionate, scholarly people who consider every reconstructive measure from a variety of perspectives. In many cases, we’ll be asked to provide alternative solutions to what we’d consider to be conventional upgrades, a quest that engages us quite often in side projects akin to reinventing the wheel – not to mention extensive research among old papers and photographs mixed with doses of educated guesswork.

And everything we do tends to be complicated by the huge fact that in almost all cases, the work must be planned without the benefit of original construction documents.

TOP-NOTCH TALENT

We’ve also learned that the professionals who get involved with this work, from the architects to the most peripheral of the subcontractors, tend to be of absolutely the highest caliber. Most do not have to do this work from a business standpoint; instead, they do it because it’s professionally gratifying.

They do it because the process, although at times frustratingly attenuated, is also often quite exciting, and in many cases those who participate are personally vested in seeing these important community facilities brought back to a state approximating their original splendor. Yes, there is prestige that comes with historic renovations, but ultimately it’s hard work.

The second reason these projects have such extended time frames is that funding is almost always a major challenge. It’s not unusual for the work on these projects to come with hefty price tags – perhaps several times the cost of similar work on non-historic facilities. Organizing the support of investors, financiers, philanthropists, contributors and benefactors of all varieties is a simultaneous undertaking that must succeed for the work to move forward.

| Venturing beneath the plywood, we found the original tile surface to be in surprisingly good condition, considering how long it had been ignored. There is a good bit of spalling, some cracking and plenty of staining, but by and large the surfaces have withstood all tests – although the ferrous plumbing has deteriorated beyond recovery. |

In other words, work on historic restoration requires patience on all fronts: You have to be prepared for the unexpected at almost every turn, and there are always situations in which you have to come up with inventive solutions to technical problems or just sit around and wait for some connected portion of the work to take place. And every single procedure must be fully documented, both for reference by those who may be called in to work on the facility in the future and to authenticate that restoring the site has not compromised its historical value.

In many cases, historic pools are located inside or adjacent to historic buildings, meaning the footprint of construction activity must be kept to minimum. There are also times when, to allow for restoration of a pool, entire portions of the surrounding buildings must be disassembled piece by piece and then painstakingly reconstructed after the watershape restoration has been completed. Either way, there is no such thing as a quick turnaround.

This is the sort of work for which very few firms are qualified, largely because they must be able to accommodate the lengthiness of the processes logistically and, often, financially. That, and the fact that these jobs don’t come around too often, is why nobody I know sees this as the main focus of their work. In our case, we might go years between historic projects and, when we get them, might end up being sidelined for years in the pauses between the study, design and construction phases.

It’s never easy, but it’s always fascinating and gratifying.

A HEARST HIDEAWAY

To illustrate the above in real-world terms, let me relate the story of an ongoing project. Still in pre-construction phases at this writing, the job already encompasses the essence of historic restoration on all the levels described so far in this text.

At the outset, I mentioned the Hearst Castle pools as being perhaps the best known of all historic swimming pools. They are indeed among the most visited and photographed of all pools ever built, and their beauty has more than withstood the many tests of time.

| The fact that the ladders – an original detail borrowed directly from the design for the pools at Hearst Castle – are in somewhat reasonable shape below the waterline is small consolation for their complete disappearance up on the deck. Restoration in these cases will not be possible: We’ll be calling in a sculptor to fabricate replicas. |

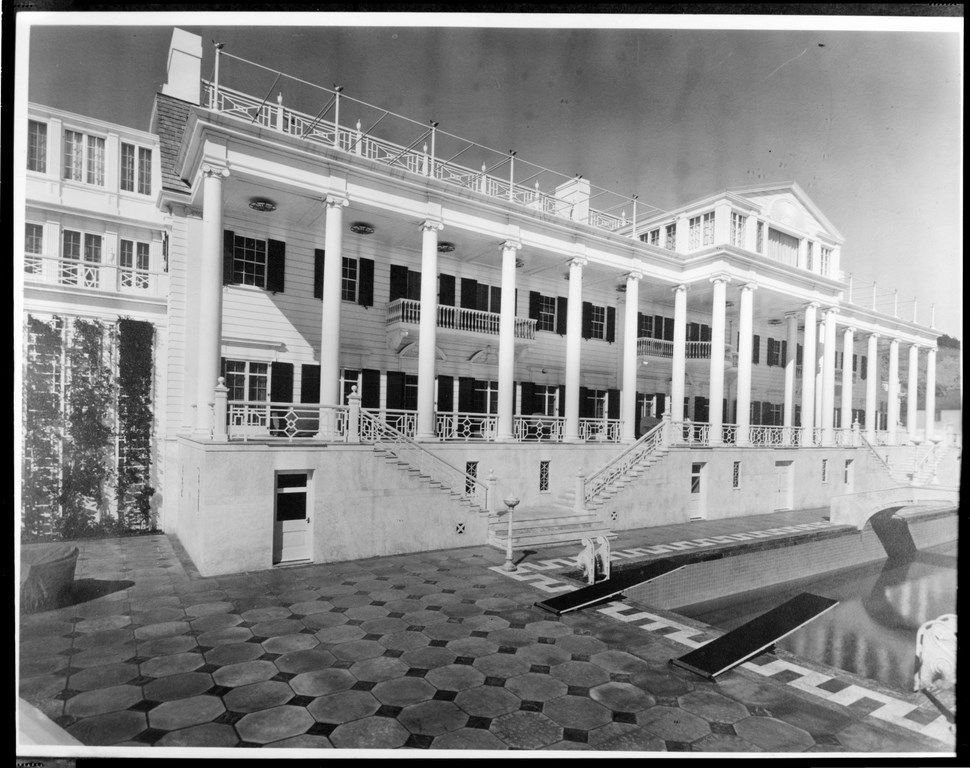

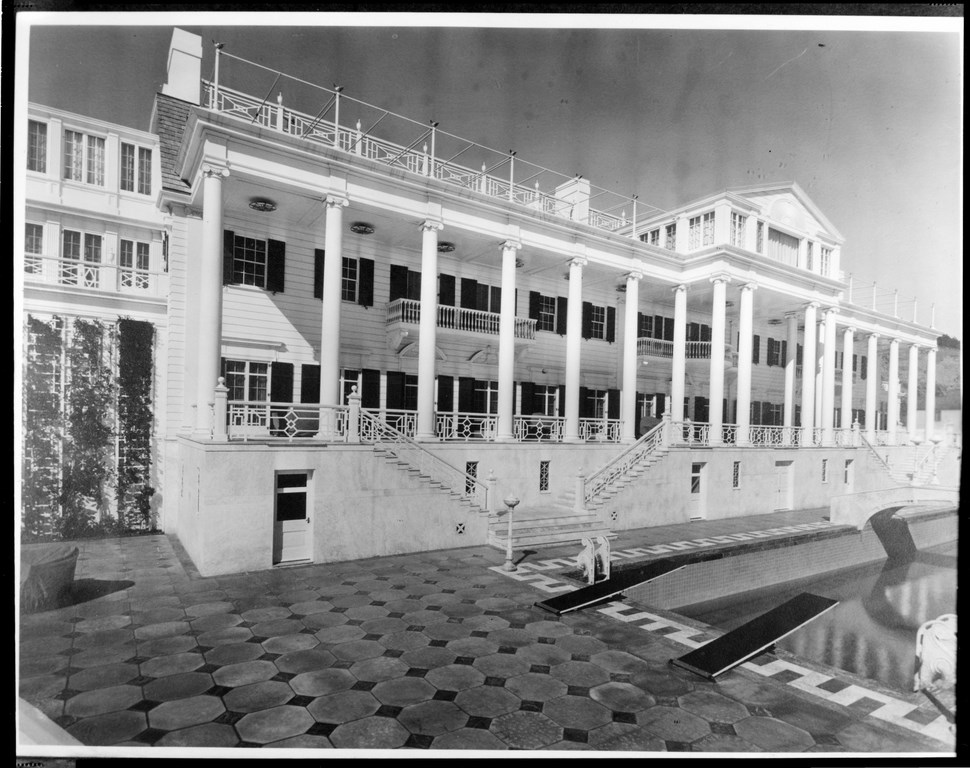

Even those who might be devoted fans of Hearst Castle are probably unaware of the fact that it is not the only such place the fabled architect Julia Morgan built for William Randolph Hearst. Indeed, not long after the castle overlooking the Pacific Ocean at San Simeon was completed, Hearst retained Morgan to design and oversee the construction of a (relatively) smaller residence located on the beach in Santa Monica, Calif.

It’s not nearly as grand as the castle, but it matched it when it came to luxury, opulence and the expression of raw wealth and power. The property sits right against the broad sand beach on the shores of Santa Monica Bay right near the fabled “Muscle Beach” area – a legendary surf spot that is credited among other things as being the birthplace of beach volleyball. A broad concrete strand runs by the western boundary of the property, which for years has been an unfortunate eyesore for the tens of thousands of people who use the strand for riding, jogging, walking or skating.

Hearst commissioned the home for his long-time companion, the actress Marion Davies, as an only slightly less ostentatious reflection of the motifs Hearst and Morgan applied at San Simeon. The estate was built over several years during the 1920s, and the original property included a 100-room home, tennis courts, guest quarters and a beautifully ornamented swimming pool featuring tile, marble decking and statuary that mimicked the Greco-Roman styling of the Neptune pool at the castle.

| Perhaps the most exciting discovery inside the pool was the relatively good condition of the tile border that spans the full perimeter of the pool’s bottom. These representatives of the glory years of California tile-making are worthy of display in a museum all on their own. |

Hearst reportedly spent $7 million on the original construction – an astronomical price tag for the times.

The estate underwent radical changes through the years, including the demolition of the original house and the addition of several buildings, some of which served as an exclusive hotel for several years in the 1940s and ’50s. The site was sold in 1959 to the State of California, which leased part of it for use as a private club and opened much of the beach to the public.

The site was in decline for many, many years before it experienced severe damage in the 1994 Northridge earthquake. At that point, it was basically abandoned and left in ruins, eventually provoking a range of prominent citizens and city officials to propose returning the property and its pool to their original glory. At this point, $24 million – more than triple the original construction cost – has been set aside for the estate’s restoration.

RISING TIDES

The city’s architect, Lauren Friedman, contacted us in February 1998 to take part in a feasibility study for restoring the site, with our portion covering the renovation and appropriate restoration of the swimming pool. Since then, we’ve been intimately involved in every step of the process.

The rectangular vessel is a massive, poured-in-place concrete structure that was originally finished with wildly ornate tile and surrounded by marble decks laid out in a stunning geometric pattern. It also featured the exact same marble handrails that are among the most appealing of all the details of the pools at Hearst Castle.

| In Hot Water

High in the Colorado Rockies sits the former mining town of Ouray. It is now primarily known as a ski resort set amid jaw-dropping mountain scenery, but one of the town’s unique attractions is a massive hot-spring-fed spa facility originally built in the 1930s. It’s an imposing body of water: 250 feet long, 150-feet wide and shaped like a football, it holds a million gallons of water and was built by miners. Resourceful folks, they reinforced the hand-mixed, poured-in-place concrete shell with steel railroad tracks scavenged from the Denver & Rio Grande narrow-gauge railway system, which at one time had its northern terminus at Ouray. The operation of the facility as originally built was truly primitive. In a routine made necessary by recurring algae blooms, the vessel would be drained each Tuesday, at which time it was pressure-washed before being refilled with water from four nearby hot springs. There was a little building on site that housed a witch’s brew of plumbing, valves and all sorts of nonsensical mechanisms – enough gear that it somehow kept running for nearly three-quarters of a century. The four water sources include Ball Park Springs, an artesian aquifer that provides the facility with 40 gallons of water per minute at 100 degrees; city water from the Uncompahgre River; OX2 Springs, which provides 270 gpm at a temperature of 120 degrees; and Box Canyon Springs, a source that emerges as a beautiful waterfall southwest of the town and provides 157 gpm at 145 degrees. Our project was prompted by a desire among state and local officials to avoid dumping hot water into the Uncompahgre River (the name given to it by the Ute Indians and meaning “the last place on the mountain where the snow melts”). This intrusion was found to be harmful to local wildlife, so we redirected the discharge from the facility – now just a fraction of the previous level – into a nearby hydroponics sewage system, the highest of its kind in the world. The pool is divided into three sections, with a spa held at 102 to 104 degrees F that flows into a warm pool held at 97 to 100 degrees. This in turn flows to a swimming pool that varies in temperature between 78 and 85 degrees. This project stands in stark contrast to the refinement of the historic restoration described in the accompanying main text: Yes, this is a historic property, but in this case, our work was far from delicate or subtle. We did little to the facility aesthetically speaking, but we sawed, bored and basically fought our way through the massive structure to run thousands upon thousands of feet of new plumbing while adding scores of inlets, drains and fittings. We cut away huge sections of the shell (which measured more than three feet thick in some places) to accommodate plumbing runs and built a new equipment room with modern pumps and filters. It was a rugged, Wild West brand of historic restoration for a town with a uniquely rugged history. — W.N.R. |

It is, in short, among the most beautiful of all swimming pools built during that or any other era, but today it is a total shambles. We do not know exactly when the pool fell into disrepair, but from the looks of it, that span would have to be measured in decades: It sits empty, hidden beneath a plywood cover that we presume was put up for either safety concerns or possibly to protect the vessel from further deterioration.

The equipment set is long gone, and the original ferrous plumbing has long since decayed beyond utility. The handrails are broken into pieces, most of them missing. Happily, however, much of the tile and decking are still there and in surprisingly good condition.

Our initial work involved pumping the mud, slime and debris out of the pool and examining just about every square inch of its interior and the surrounding areas. We conducted soils tests, core-drilled samples of the shell (which turned out to be surprisingly sound) and basically took measurements of every conceivable elevation, dimension and contour.

The pool is 103 feet, five inches long by 22 feet, one inch wide. We’ve determined that those odd dimensions were dictated exclusively by the dimensions of the tile: The shell, it seems, had been sized to accommodate the tile without necessitating any cuts!

We also discovered the remains of an entirely separate pool in the ground beneath the nearby parking lot. It’s little more than a curiosity at this point – and an example of the sorts of surprising things you can run into in these situations. Nobody knew a thing about this second pool before we found it: It wasn’t evident in any photos, documentation or memory, but there it sits in faded glory, encased in asphalt.

FORWARD MOTION

Armed with this odd trove of information, we developed a plan for the restoration in association with the project’s lead architect, Fred Fisher & Partners of Los Angeles, and a host of experts involved in the project on a variety of levels. The contractor is Pasadena, Calif-based Pankow Special Projects – another key player on the design team. The scope of work as we defined it includes:

[ ] Removal, labeling and cataloging of the decking material to facilitate trenching around the pool shell for installation of new plumbing and the subsequent (and exact) reinstallation of the deck [ ] Replacement, repair and sprucing up of the pool’s interior tile surface [ ] Replacement of the handrails (an effort that will require contacting with an Italian sculpture studio or marble artist of some kind) [ ] Installation of a new equipment set that meets health-code standards for water treatment and turnover rates.| Military Precision

The U.S. Military Academy at West Point boasts several beautiful indoor pools. While none of them is historic per se, the Arvin Gymnasium that houses them certainly is. The old facility was named after the first West Point graduate to die in Vietnam. In this case, we rehabilitated three pools inside the facility, upgrading their systems and reworking various finishes and ancillary elements while making sure that nothing we did made any sort of visual dents in the gymnasium itself. (For two of the pools, in fact, our firm has overseen renovations twice during the past 20 years.) Without rolling through the details at length, this form of historic-renovation work is about taking down parts of the historic building, labeling and cataloging every single scrap of material before beginning to renovate the pools with all that the process entails. Once the pool or pools are in order, the project involves reconstructing the building and returning it to its original state – not an easy task by any means. Where some projects are all about historic sensibility and nuance, projects like these where the pool is an open book but the building is the source of historic concern are largely about being careful and systematic. The scope of the work encompassed upgrading the Crandall Pool, a 50-meter competition pool with a 10-meter diving tower; a 25-meter intramural pool; and another vessel for general use and military training. The Crandall pool was built originally as a six-lane pool, so remodeling the vessel to include eight lanes required the widening of a portion of the building. It has a unique movable bulkhead that retracts into the floor of the pool; we’d been called in to rework and repair that system. Because of the age of the building, there was a huge challenge with asbestos abatement. This meant we had to coordinate our activities carefully with the Army Corps of Engineers. In the accompanying text, I mentioned that in many cases the people who work on these projects have some sort of vested personal interest. In this case, as a retired two-star U.S. Air Force General, I was intensely interested in the history of this facility and its use, and I was highly motivated to provide the cadets at West Point with a top-notch place to swim, compete and train. This project stands as point of distinct professional, personal and even patriotic pride. — W.N.R. |

This list simplifies things somewhat, but to a large extent the specific measures here are not all that far removed from a typical renovation project for a big commercial pool.

What will set this project apart is the attention to historic detail and the ways we’ll reconcile the need to update the system on the one hand while on the other holding things as close as possible to their original appearances. As is typical of these projects, there are no original plans, which means all we have to guide us is old photographs and the advice of architectural historians.

One of the largest challenges we face is that this was originally designed as a residential pool without any thought being given to health and safety codes. This means that we have to make some changes to the pool and its systems to bring them up to code, but it also means we’ll have to seek variances, some of them significant, in order to preserve the vessel’s historic nature.

For one thing, the pool is finished in richly colored tile. In most places, of course, public swimming pools must be white and white only. In this case, resolution is pretty straightforward in that the health department has no real choice but to roll with this major variance. But even with an issue as apparently simple as this, the process of arriving at a point of permission and securing all the proper blessings is anything but simple or linear.

For another, the pool is three feet, ten inches deep when, according to commercial pool-safety standards set forth in California Code of Regulations, Title 24, Chapter 31B, Public Swimming Pools, which says that no pool’s shallow end can be more than three feet, six inches deep. Again, this is a case in which aligning the pool with modern standards would basically involve ripping up the pool and rebuilding it – an intrusive measure that would be historically unacceptable.

Beyond that, we can easily comply with current codes in a number of ways, including the installation of dual main drains (to avoid the risk of suction entrapment) and the revamping of the circulation, filtration and chemical treatment systems and plumbing to meet standards for water quality and turnover rates. We’ll also be adding deck drains. In all these cases, the visual alterations from the original are relatively minor, acceptable to historians and a crucial nod to the health and safety inspectors.

THE PAST REGAINED

We’re currently in the design process and working with the contractor and various state, county and city authorities in addition to the Ahmanson Foundation, the project’s primary donor. As it now stands, the physical work will begin sometime in 2007, nearly ten years after we first caught wind of the existence of this place.

| With it’s grand staircase, the building that once stood alongside the pool is long gone and beyond restoration, but the pool itself will again reflect the beautiful design sensibility of architect Julia Morgan, right down to the elegant handrails and the shimmering surface of the tile-framed water. (Photo courtesy Santa Monica Historical Society Museum/Bison Archives) |

Even given our long involvement in the process, I’m still amazed by the idea that in the not-too-distant future, we’re going to be able to see and appreciate another example of William Randolph Hearst’s mind-blowing collaboration with Julia Morgan, arguably the most significant of all of history’s female architects. It’s as if we’re raising buried treasure, lost long ago and nearly forgotten.

Of course, this work has an elephantine gestation period and can be remarkably time-consuming and at times frustrating, but just the opportunity to work with so many talented people on a project of such real value to the community and the state’s history carries a value that cannot be measured in compensation, professional pride or community acclaim.

It’s one of those rare things in life where the journey is truly its own reward.

William N.Rowley, PhD, is founder of Rowley International, an aquatic consulting, design and engineering firm based in Palos Verdes Estates, Calif. One of the world’s leading designers of large commercial and competition pools, his most notable projects include partial designs for the competition pools used in the Olympic Games in Munich (1968) and Montreal (1972), and he acted as aquatic consultant for the design of the Olympic Pool Complex in Los Angeles (1984). His projects also have included a wide range of non-competition pools, including the White House pool in Washington, the Navy Basic Underwater Demolition Training Tank in Coronado, Calif., and the resort pool at the Hyatt Regency at Kaanapali Beach on Maui. Dr. Rowley is involved in a range of local, state and federal entities for which he consults on construction and safety-code requirements and was recently named a fellow of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.