Living Art

To those who see art as frivolous and ultimately unnecessary and expendable, we offer as a counterweight the following from Austrian poet, Ernst Fisher: “Art is a driving force in bringing humankind to greater quality of life, and it is therefore an absolute cultural necessity.”

For the artist, tremendous responsibility comes with that necessity. Indeed, those who expose others to art bear a burden in shaping entire cultures as people around them come to accept their artistic output as essential threads in the social fabric. Think of Brunelleschi in Renaissance Florence, for example, or Gaudi in modern Barcelona.

When we as watershape or landscape designers seek to expose others to our works of art, we accept a profound moral responsibility whether we work in the public or the private domain. At its core, our responsibility is to seek and communicate truth. As we see it, one and all who fall under the broad umbrella of the watershaping arts should be passionate in that quest for truth – and turn their backs on pretenders who are too lazy or greedy to take on the burden.

As artists, in other words, we should be doing all we can to influence society in a positive way. And you don’t have to be a Picasso, Rubens, Einstein or Frederick Law Olmstead to make a difference: As artists, we all share the ability to shape culture and the realities of people’s lives through our insightful use of water, stone, plants and light in all the various styles in which they can be applied.

BEAUTIFUL MINDS

When you look up the word “art” in various dictionaries, you’ll find the word “skilled” – that is, “possessed of the ability to do something well” – mentioned in almost every definition.

When you consider the broad sets of skills and forms of information required to perform at the highest level of watershape and landscape design, engineering and construction, it becomes clear that the process of creating art should be rational and not something that takes place in a state of intoxicated inspiration.

The information we bring to our work should go far beyond the suddenness or subjectivity of cultural clichés and fashion trends and should instead deal objectively with each object and space we create. When an observer sees that space, thinks about it and, most important, passes some form of judgment on the experience, this is what ultimately influences a culture.

Thus, when you break it down to the most basic (yet sophisticated) level, our projects should generate the sort of qualitative change mentioned at the outset of this article, both for individuals experiencing our work and for the overall shift in society that results as multiple observers judge and qualify their experiences.

| ‘Those who expose others to art bear a burden in shaping entire cultures as people around them come to accept their artistic output as essential threads in the social fabric. Think of Brunelleschi in Renaissance Florence, for example, or Gaudi in modern Barcelona.’ |

It is our assertion that the watershaper should be motivated primarily by just this sort of sincere desire to improve the quality of life and public esteem for art and never be satisfied to appeal to the lowest common denominator. While financial gain is important, it won’t typically drive a project to the best conclusion; furthermore, the need to do business does nothing to negate the artist’s social responsibility.

Watershaping and landscape architecture are great, great art forms, but their histories past and present are littered with examples of work created without this necessary sense of social responsibility – work that consequently falls well short of its best potential. If the goal of the artist is to change the quality of people’s lives, striving for anything less means we are not working in full acceptance of our creative responsibility.

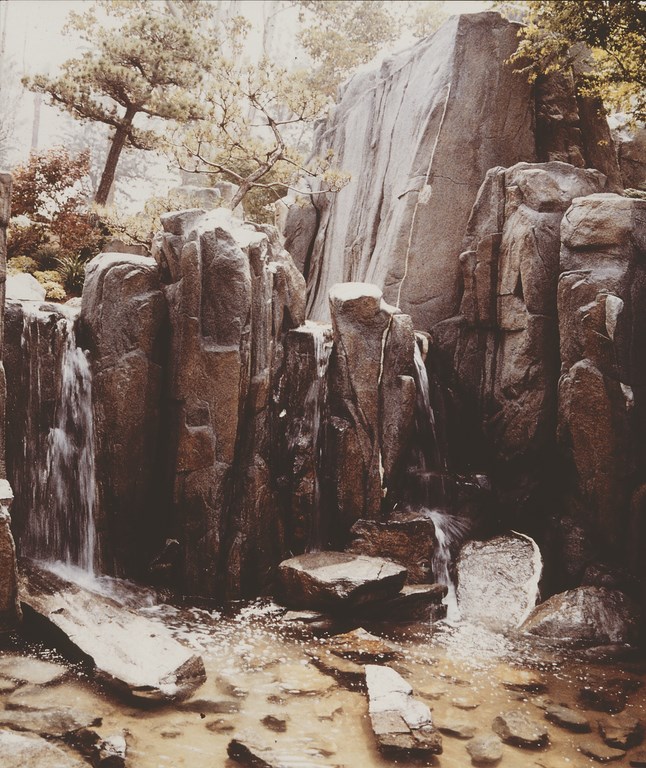

When we meet that responsibility – when everything snaps into place with respect to water, rockwork, plantings, hardscape, lighting and various amenities – all of those elements subordinate to the fuller experience provided by the overall composition of those elements.

In listening to a symphony, we might observe the playing of an oboe or viola or timpani, but the experience is created by the collection of the sounds they make within the totality of the composition. By the same token, the best rockwork does not jump out and proclaim its presence to the viewer, but rather works as part of the composition in creating the overall experience to create a picture.

THE ARTISTIC VOCABULARY

That overall composition is what most great art is all about, and we’d argue that watershapes and landscapes have just that sort of power and influence when composed by skilled practitioners in full awareness of their social responsibility.

Our art involves visual communication that often transcends verbal explanation. That’s why there’s a certain awkwardness to our presentation here, basically resulting from the fact that the notions we’re discussing aren’t easily captured in words on paper. But if you think about it for a few minutes, the philosophical ramblings move inevitably to a simple observation: What we do as watershape and landscape designers is easily more important than most of us tend to recognize.

| ‘It is our assertion that the watershaper should be motivated primarily by a sincere desire to improve the quality of life and public esteem for art. While financial gain is important, it won’t typically drive a project to the best conclusion; furthermore, the need to do business does nothing to negate the artist’s social responsibility.’ |

What we’re saying might come across as arrogance – or maybe simple vanity. But when you think about the bigger social context in which we work, there’s no reason why our work should not or cannot be considered in the same sentence as the artistry of Michelangelo or Frank Lloyd Wright, because our work is similarly influential and has a similar role in shaping the quality of life in communities around the world.

Yes, what we do may be hard to capture in words, but our work should always strive to edify and instruct and guide perceptions.

In composing a project, it’s important to keep a key set of issues in play as you examine your progress from a variety of points of view, keeping foremost in your mind that the outcome will have great influence the experience and judgment of the observer. The key to success is to not only understand these factors, but to put them into practice as the design process unfolds:

[ ] Dynamics: This refers to the relationship between motion and the forces that affect that motion. An example of dynamics in design can be seen in quality rockwork that goes beyond simply mimicking the forms of nature but seeks to capture and represent the processes that resulted in those forms. A rock formation is not a snapshot that captures a single moment, but is instead a moving picture that tells the story of all the forces of nature that have influenced that formation through vast, geologic time.

| ‘When we meet that responsibility – when everything snaps into place with respect to water, rockwork, plantings, hardscape, lighting and various amenities – all of those elements subordinate to the fuller experience provided by the overall composition of those elements.’ |

[ ] Subliminal registration: It is extremely important to realize that a great deal of information is transferred subliminally, that is, below the threshold of conscious perception. The movement of shadow, the power of reflections on the surface of still water, the complex sounds of falling water, the subtle coloration of rockwork or hardscape: These are all examples of design elements that will communicate subliminal impressions – and it’s important to consider that perception happens within a millisecond.

[ ] Kinetics: This key element is defined as the study of all aspects of motion. In a landscape, kinetics are experienced both immediately, as in the way a weir will influence the form of falling water, and in less immediate ways, such as in the way rock forms are influenced by powerful forces of nature. There is movement or potential energy in everything we see, even when things appear to be stationary.

[ ] Geomorphology and Geology: When creating naturalistic designs, it is critical to understand and embrace the study of topographical configurations and the evolution of landforms. One example is found in the concept of the talus, which is simply a piece of rock that has broken off from the main body of a formation. You can see by the shape of the talus that it was originally part of another nearby rock structure. Applying this concept lends a sense of the passage of huge, geological time frames into a compositon.

|

Building a Narrative Whether the design seeks to awaken, cast shadows or bring light, whether it seeks to delight or to inspire quiet reflection, the work you do should never be seen as a mere “description” of an idea. Rather, and in a very real sense, we should seek to tell some kind of story. In other words, when looking at our work or moving through a space we’ve shaped, the viewer should sense and see the evidence of a process that has unfolded over time. This is certainly and easily true in the case of naturalistic designs that seek to capture the processes of nature in the essence of the work. It is also true in architectural settings, where the relationships between the elements tell a story about how light and water interact, or about how hardscape and plantings combine to create an impression of growth and permanence, or about how the hand of man conforms to the necessities of the site. — P.di G. & M.H. |

[ ] Phenomenology: This is the study of human experiences in which subjective responses are temporarily left out of the equation. In other words, there are certain predictable responses to forms within a landscape: A narrow, winding path, for example, will cause a visitor to move more slowly through a space than will a wider, straighter path, and objects that are dissimilar to those immediately surrounding them will draw the eye and create a focal point. These human responses to the designs we create are what drive the experience of the observer and must be considered fully as we proceed in our work.

[ ] Sincerity: Working free of pretense or deceit in feelings, manner or actions is crucial to the success of any form of art. With watershapes and landscapes, the pretense we must avoid is the idea that the work is about the skill of the designer. Our aim should not be to impress with cleverness, but to use our knowledge and skills to create an experience.

It’s not that we shouldn’t strive to create dynamic spaces and objects within in them, but that we should always keep in mind that every element plays a role in the overall composition. In a very real sense, form follows function and the motivation dictates the form. At times that may mean creating extremely retiring and subtle forms; at others, the situation might require great boldness. In any event, sincerity of purpose in creating an experience for the observer will help guide you as you seek to tell the stories that stand behind the finished project.

ART & SCIENCE

If what we do is all about visual communication, just what is it we’re trying to “say”? Almost without fail, our art exists to communicate information about nature and ourselves. In an extremely tangible sense, this means that art and science are inseparable in the design process.

When starting a project, in other words, it is critical to begin by defining real issues and objectives rather than by pursuing subjective impulses. Our work should communicate and speak directly to the viewer. If you have something to say by way of your design then do so, because what a project is saying is what gives it purpose.

| ‘There’s no reason why our work should not or cannot be considered in the same sentence as the artistry of Michelangelo or Frank Lloyd Wright, because our work is similarly influential and has a similar role in shaping the quality of life in communities around the world.’ |

It is in the melding of art and science that we see the great distinction between objectivity and subjectivity. Subjectivity can only reflect social conditions of the day or the condition of the individual viewing the art, while the combination of art and science have the much broader ability to change those conditions and are therefore necessary to advance society and influence the individual.

Most zoo designs, for example, are little more than misinformation borne of the exigencies of the setting. Designing a natural habitat for lions is immediately influenced by the fact that the lions will see you seeing them in a so-called “natural environment.”

Truth be told, if one of those lions could gain physical access to you, he would pounce on and perhaps kill you. That fact alone means that the design of the habitat will be far from “natural” and will represent nature only in certain respects. The safety and welfare of the animal and the public, the need for viewing spaces, constraints of size and space for the habitat, proximity to other habitats – all these issues influence the design.

| ‘With watershapes and landscapes, the pretense we must avoid is the idea that the work is about the talent of the designer. Our aim should not be to impress with cleverness, but to use our talent and skills to create an experience.’ |

Yet the zoo is there to enlighten visitors so they walk away with a greater appreciation of the animal in a “natural” setting, a setting that, however artificial, is often far removed from the visitor’s immediate condition. The designer of the zoo exhibit must therefore balance the practical and physical circumstances of the setting with this higher, informative purpose in mind.

In many of the world’s finer zoos, this communication proceeds flawlessly and we perceive a keen integration and balance of the practical with the need to represent the natural world. In other zoos, unfortunately, the greater purpose is completely lost in the design work, and the animals become little more than set pieces intended to entertain visitors and generate revenue.

A big part of the design challenge is to balance realistic conditions and constraints of the work with artistic responsibility. To edify and instruct in such a setting involves a magic recipe that blends art, science and a passion for people and their experiences.

CONSTRUCTIVE LEARNING

We are fortunate these days to have a great many resources from which to draw specific, objective information we can use to drive our designs. Not only do we have legions of artists and scientists alive and working today, but now we also have a tradition of past masters from which to draw.

That tradition is rich with wisdom that can be applied in every aspect of our work. Fredrick Law Olmstead once said, “Well-designed parks are works of art.” Galileo wrote, “Images are the starting point for all of our thinking and feeling.” And Picasso was known to express his view that museums were the worst possible place to put art, basically because people visiting museums tended to carry preconceptions about the nature of the art they were about to see. In each case, there’s a kernel of insight we can use to inform our work and help us see what’s truly at stake.

| ‘A big part of the design challenge is to balance realistic conditions and constraints of the work with artistic responsibility. To edify and instruct in such a setting involves a magic recipe that blends art, science and a passion for people and their experiences.’ |

We are lucky in our trade because our artistic expressions have advantages over paintings hung on walls: Our work exists alongside homes or in public spaces where people are in the presence of our work not for the sake of viewing art, but as part of going about their daily lives. As a result, they will perceive the space in a variety of ways that will often have little or nothing to do with “art appreciation.”

The ubiquitousness of watershapes, landscapes and architecture gives us an opportunity to change observers’ qualitative experience. In that process, we bring into play aspects of our own learning and how we have been influenced by ideas that have had transforming influences on our lives.

| ‘Our work exists alongside homes or in public spaces where people are in the presence of our work not for the sake of viewing art, but as part of going about their daily lives. As a result, they will perceive the space in variety of ways that will often have little or nothing to do with ‘art appreciation.’ |

That distinction is key: The notion is not to show someone a mirror image of nature, but to raise the observer’s consciousness by giving them an insight into nature. When we succeed in taking artistic expression to that level, we offer observers insights into the dynamics of the world around them – which naturally raises their interest and may even help them develop an understanding, appreciation and respect for nature and their own connection to it.

In this sense, we are products of our teachers and those who inspire us through tradition and direct contact. In turn, we also become teachers, and it is this transference of information, be it overt or subliminal, that binds us to our antecedents, to those who observe our work in the here and now and to those who are yet to come.

SEEING WITH THE MIND

What we’re talking about here is the management of perceptions and understanding how people see things – perhaps the most important factors of all in making good, accessible art.

The brain has a tendency to assume and organize things into meaningful spatial units. Using a fallen piece of talus as an example, one’s brain assumes that the piece fell from a larger rock formation. This happens because of the brain’s natural tendency to organize what it sees and, in this case, to reassemble the pieces into a meaningful shape. As Picasso said, “Give the viewer all the pieces and they will make the picture.”

His statement cuts directly to the difference between perception and seeing: Seeing is automatic, while perception must be provoked. Perception takes place not in the eye but in the cerebral cortex and is a product of thought.

| ‘In the art of streamcraft, for example, the result isn’t individual boulders, cobbles, shorelines or eddies, but the greater perception of the time-force and motion of the stream moving through the landscape.’ |

To generate perceptions in our viewers, we must first have an idea in our own minds of what we want them to perceive. Consider a painting of a tree: The point of many great paintings of trees is not simply show the tree, but to tell the story of the effects of growth, age and weathering by wind, rain, heat, cold, lightning, insects and even fire. On the surface, the observer sees the tree, but upon closer consideration of all the complexities that combine to produce a perception, he or she gains insight, through the artist, into the metamorphoses that occur in the life of the tree.

When you’re creating art, you cannot possibly engender such perceptions in the viewer unless you do so with forethought, information and the all-important sense of artistic responsibility. In the art of streamcraft, for example, the result isn’t individual boulders, cobbles, shorelines or eddies, but the greater perception of the time-force and motion of the stream moving through the landscape.

We must always keep in mind that the perceptions we evoke are a result of the viewers’ participation in the environment – a participation that works to increase their understanding of the stories that surround them. Physical participation, that is, relaxing in the shade of a tree, swimming in a pool or walking down a path, is one level. A second, deeper level of participation is psychological and is the realm in which all of the elements of our artistic responsibility come into play.

It doesn’t matter if you’re working in swimming pools, naturalistic watershapes or architectural fountains: In all cases, we work to create perceptions in the minds of observers and ultimately seek to create a judgment in their minds. Only then do we begin to live up to the true potential of what it means to be an artist.

Philip di Giacomo has been creating environments using artificial rock for more than 40 years. His company, di Giacomo, Inc., is based in Azusa, Calif., and is home to his design and manufacturing operations. His passion and spirited participation in landscape architecture has led him to produce many art pieces, including an entire series for the 1990 convention of the American Society of Landscape Architects. Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at [email protected].