Awakening a Dream

Certainly one of the world’s most unusual watershaping achievements, ‘Le Reve’ is a Las Vegas-style aquatic production that carries audiences into an amazing dream world of water, light, music and incredible acrobatic skill. To achieve the water effects, former Cirque du Soleil producer Franco Dragone turned to Aviram Müller and Canada’s Kaarajal Design Aquatique – and the result is a marriage of watershaping art and technology unlike any other.

Franco Dragone’s design team first contacted me late in 2003. His company, which organizes groups of design firms to create some of the world’s most elaborate stage productions, was working on a new Las Vegas extravaganza for hotelier Steve Wynn.

Wynn’s properties are famous for their water effects, including the wonderful fountains in front of Bellagio on the Las Vegas Strip. I was told that his then-current project, the Wynn Resort, was to feature similarly spectacular water elements – one of which was to be an aquatic theatrical production known as “Le Reve” – that is, The Dream.

Dragone is perhaps best known as one of the visionaries who created Cirque du Soleil. In striking out on his own after more than a decade’s association with that phenomenally innovative troupe, he saw “Le Reve” as the ultimate achievement in theatrical spectacles and assembled a design team capable of rising to new heights.

By the time I spoke with Michel Crete, Dragone’s Montreal-based chief designer, in 2003, the team was already deeply engaged in production design and had reached a point where realities and practicalities needed to be addressed. My firm, Kaarajal Design Aquatique, had the important advantage over other capable aquatic-design companies of being located in the Montreal area: Dragone saw proximity as being as important to effective collaboration as were independence, flexibility and artistic imagination.

In our first meeting – an interview, really – we found good chemistry almost immediately and agreed to work together. The ensuing year and a half of development would prove to be extremely challenging. Ultimately, however, it was all extremely satisfying.

IN THE ROUND

As soon as we came on board, we were immediately confronted by a number of working constraints: All of the elevators and platform structures that constitute much of the staging for the show, for example, were already in place (and, perhaps more important, had been accepted and approved by the production’s insurance company). Even the pumps had been selected and installed. As a result, we were forced to invent highly creative effects within a predetermined framework.

The narrowness of those parameters, however, was more than balanced by the production designers’ desire to achieve effects that had never been seen before. In fact, we were told to forget the computer simulation of the production’s centerpiece system we’d been shown and were immediately asked to search for the most interesting and creative possibilities available. So even though there were existing conditions we had to accommodate, Dragone had also opened a tremendous creative window for us.

But I get ahead of myself: By way of background, “Le Reve” takes place in a dedicated theater designed solely and exclusively for this one production. It includes a 2,000-seat amphitheater with a central stage, and no seat is more than 42 feet from the action. Because of this theater-in-the-round configuration, there’s no backdrop: All performers and production elements either appear from below the water or descend from the ceiling.

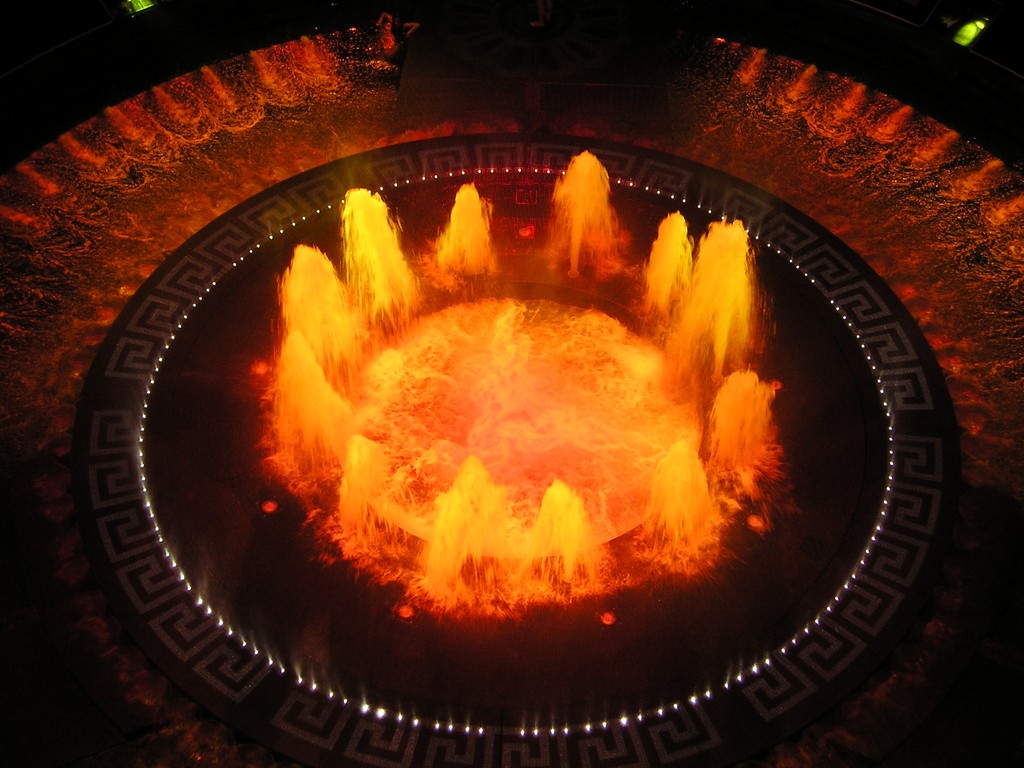

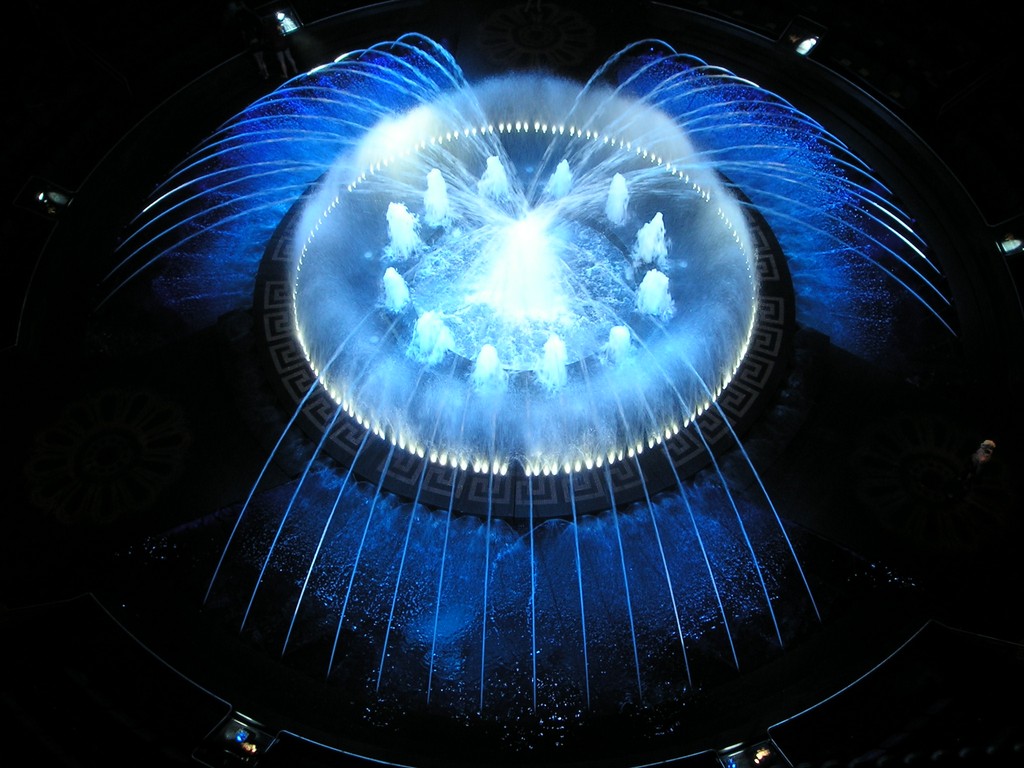

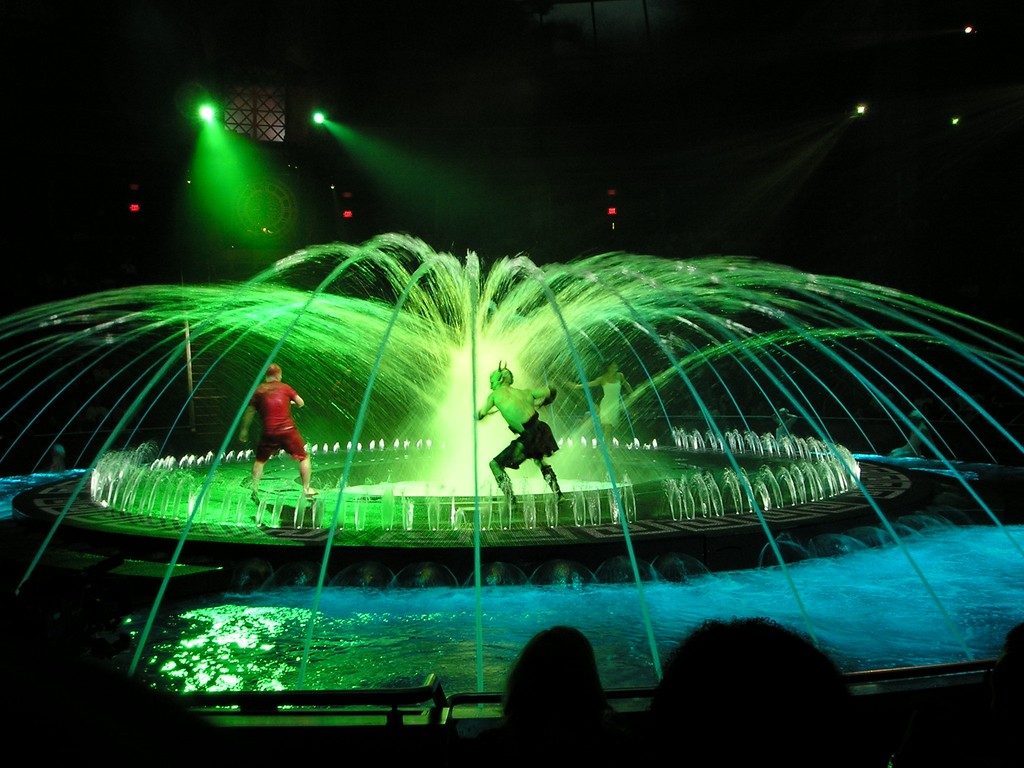

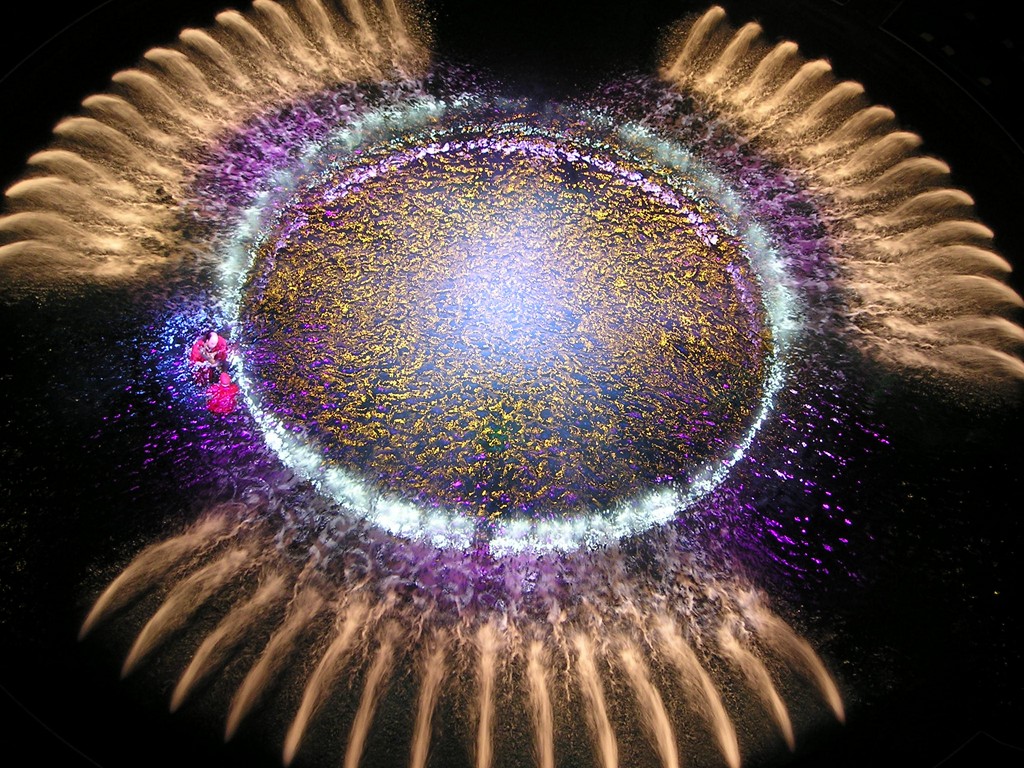

| The complex fountain effects take on new significance and drama when acrobats interact with the water across multiple staging levels. The unique achievement of this theatrical production is the way the systems have been devised so that there’s nothing entirely automatic: The timing of each effect is controlled on the spot by a team of technicians who watch the performers and make minute adjustments to coincide with what’s really happening ‘on stage.’ |

The “stage” itself is a circular, poured-in-place, reinforced-concrete basin 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep. It contains approximately two million gallons of water and is set below a massive cupola that rises 30 feet above the water level. This cupola carries lights, rigging and other staging equipment including a variety of illuminated forms and is also fitted with four big video screens that cover its entire surface and are used throughout the performance. In addition, the rigging features a video sphere along with flying mannequins, fire and snow effects and more.

Moving in three dimensions through this space are 86 performers – all of them world-class gymnasts, divers and circus acrobats who accomplish near-superhuman physical feats within a constantly changing environment of special effects. Indeed, for all of the mastery and dazzle of the theatrical systems, the movement and artistry of the performers is ultimately what animates the production.

And to say the production is animated is to put it mildly. It was a situation in which physicality, artistry and engineering had to work fluidly together – and did so in remarkable ways. Much of the credit for the show’s integral vitality goes to Michel Crete, with whom I collaborated closely and who is famous for his work on Cirque du Soleil’s “O,” which in some ways served as a precursor to “Le Reve” (but with simpler aquatic elements).

Crete is himself a talented designer who works easily with both nuts-and-bolts technical issues as well as purely aesthetic concerns – often simultaneously. I, too, have both an artistic and technical background, so I was comfortable in his kind of creative environment.

PRECISE THEATRICS

From the start, everyone involved with the water effects was thinking about how the movement of the water would affect an audience. For his part, Wynn wanted to make a dramatic statement that would be as spectacular as (yet different from) Bellagio, whose fountains are so elaborate and engrossing that the same people keep coming back to see them over and over again. We wanted to operate on that level, creating a theatrical event a viewer would happily see several times because the complexity of what they were observing would repeatedly and constantly engage both imagination and memory.

| The skills of the acrobats are truly astonishing as they move through a challenging environment and deliver performances that are athletic, exciting, sensuous, daring and awesomely entertaining. That they do so in such intimate interaction with water and in constantly changing conditions is a tribute to their physical abilities – and to the imaginations of those who organized and devised the show. |

Of course, artistic achievement at that level requires a tremendous array of precisely designed, installed and controlled technology. Behind each individual effect, in fact, is a dedicated, complex and sophisticated system, expertly run and maintained by one of dozens of talented technicians.

Simply moving all that water requires a staggering amount of energy: The aquatic systems are driven by banks of pumps ranging from 5 to 500 horsepower, every unit with a variable-speed drive to accommodate the different operating conditions encountered during a performance. Just as impressive, the lighting system has a two-million-watt capacity and is made up mostly of low-voltage LED fixtures both for safety in and around the water and for efficiently managing electricity use.

Inside the basin are elevators that raise and lower five platforms on both sides of the waterline, and each of the five carries a variety of water-effect elements including spray jets, sheeting waterfalls, rain curtains, fog effects, dancing vertical plumes and more. When all the platforms are raised, they cover about two-thirds of the basin’s surface area.

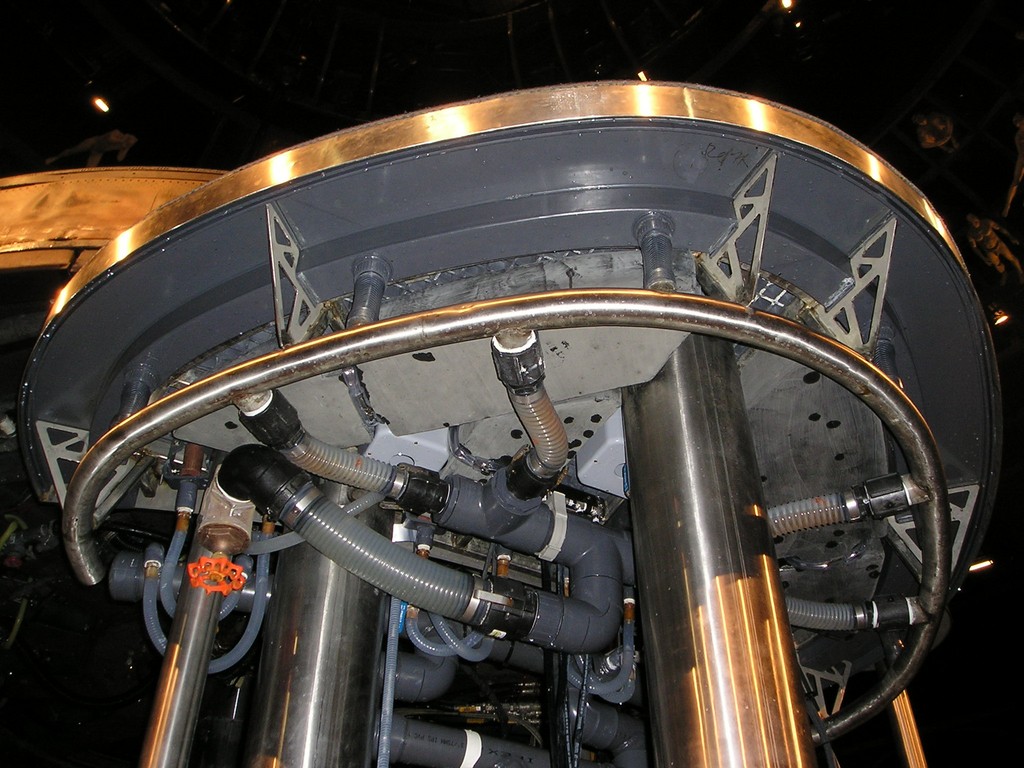

The platforms rise from the water on hydraulically driven telescoping/scissoring mechanisms, with varying combinations of their water effects already operating. The main supply lines are stubbed up on the basin’s floor, where they are connected to flexible tubing that moves up and down with the platforms. These tubes run to various manifolds on each of the platforms, making the bottom of each a complex mesh of plumbing, cabling, chambers and rigging.

The variable-speed pumps are programmed to provide varying flows to match the ever-changing demands of the show. As the platforms move up and down and various features actuate or rest, each one may operate at a different flow rate depending on the needs of the show’s choreography and will automatically adjust to create the desired effect. There are literally hundreds of different configurations, each with a different hydraulic specification.

All of the pumps were manufactured by Paco Pumps (Brookshire, Texas), while much of the fountain equipment was provided by Crystal Fountains (Toronto). We also used a number of industrial fixtures from IMS (Toronto) to create effects not found in standard fountain technology; in addition, we ended up fabricating a number of components ourselves to suit a number of unusual applications.

INTO VIEW

Within this general framework, we faced enough specific and unusual technical challenges that I could easily fill a book. The center platform, for instance, is 15 feet in diameter and rises 10 feet above the water level, and we needed to install raindrop and waterfall effects around its perimeter.

The challenge was that we only had an inch and a half of space within the steel frame at our disposal. This meant we had to figure out how fit the waterfall fixtures, which normally would be a minimum of three inches wide, into a space half that width. We also had to figure out how to distribute the water evenly around the entire common manifold so raindrops would all be uniform in size at each orifice.

To make it happen, we custom-fabricated a PVC manifold that we wrestled into the structure. This small manifold contains a system of special guides that ensure even flow around the platform, and we set it up to be fed by multiple intersecting pipes connected to a central flexible pipe that travels up and down with the lift. This was typical of the challenges we faced with each platform: They all needed multiple manifolds, feed lines and jet fixtures, and everything had to snake around conduits feeding the platforms’ complex lighting systems.

Adding to the challenge, of course, was the fact that everything we did would be in relatively plain view of the audience. We wanted to minimize visual distractions, so we did all we could to bundle, tuck, mask and jigger all of these systems into extremely compact spaces – always without compromising function or reliability in any way.

It was an arduous process. I made three trips to the site, each of them three weeks long, to address a variety of specific details. In one case, for example, we discovered a problem with water uptake by flexible waterfall boxes in the round “cliffs” of the platforms: They absorbed so much water that the fixtures undulated under pressure and eventually broke apart. We had to replace all of these units immediately with ones made from marine-grade polyurethane – a process that meant we had to spend a full three weeks reinstalling and reconnecting hundreds of these waterfall boxes.

| Behind all the theatricality is a core system of elevators that had to be immediately responsive to every technical demand – on the one hand as fully functional platforms for waterfeatures, and on the other hand as structures that would stay out of the way of the performers and offer no significant visual distractions to audiences. It was a remarkable balancing act, and seeing it even now is a thrill – in all ways a dream come true. |

Another unusual problem: Many of the manifolds, which numbered in the hundreds, were damaged in shipment from the manufacturer in Quebec. This meant that we had to reconstruct many on site, every one of them to precise specifications.

While some of this installation work was done with the basin empty, much of it could only be done with it full of water so we could see what worked in the diving envelope and what didn’t. We met often, learning what posed problems for the acrobats and making adjustments. Suffice it to say that my visits were challenging and filled with extensive problem solving and inconceivably precise system refinement.

FINAL ADJUSTMENTS

Unlike almost all other watershapes, the systems we developed for “Le Reve” were conceived as part of a live performance in which human beings would constantly interact with the features, fixtures and equipment. As a consequence, there was a six-month period leading up to the show’s premiere during which we worked directly with Dragone and his installation crews on site at various intervals, running through hundreds of technical and aesthetic issues while always considering the needs of the production as well as the safety of the performers.

Through this period, he steadily added, modified or replaced various elements of the show and was always challenging us to come up with fresh ideas and solutions. Sometimes this meant no more than adjusting cues in the computer-driven show controls, but often it led us to reconfigure some of the equipment on the fly.

|

Preserving the Wonder A system as complex as the one described in the accompanying text requires a tremendous amount of careful maintenance: Each performance works only if there’s perfect functionality, so there’s never any room for error and every aspect of system performance and operation must be monitored constantly – and repaired if necessary. This is why, every morning, a team of divers goes through a detailed checklist, making certain that all components are in working condition and not showing appreciable signs of damage or wear. The variable-speed pumps get the same treatment: Technicians constantly monitor their output and adjust each one as necessary. If malfunctions crop up, pumps are immediately pulled, replaced and set aside for eventual repairs. Once each year, the basin is drained and cleaned, and much of the equipment is disassembled for internal inspections. With maintenance routines like these, it’s easy to see why, since the show’s premiere in 2005, there has never been a system failure during a performance. — A.M. |

It was a period of tremendous motion and invention in which each of the effects had to be calibrated with extreme precision so each would deliver exactly the amount of water the production designers wanted to see. At the same time, we needed to build in enough operational flexibility to accommodate the immediate needs of each scene as well as slight variations in performance. This was a huge challenge: They wanted the show to be precisely programmed, but at the same time, they wanted us to recognize that they were working with live performers, not robots.

Avoiding this programmed, robotic impression was crucial to Dragone, so while there are multiple computers that control all of the various lighting and water systems, each effect or sequence of effects is nonetheless managed by technicians who initiate the programs in response to what’s happening in the performance. In that sense, “Le Reve” is an extreme example of technology interacting seamlessly with human performers, divers and system operators.

Once most of the theatrical effects (including the water) were organized, Dragone spent another several months refining the show – working with performers, adjusting the sequences of effects and at just about every turn requesting various system adjustments. He is a passionate, creative man, and he established a working environment in which everyone involved was at the ready to respond to the flood of decisions he was making.

The human element was a constant factor and continuously affected the way we developed and adjusted the systems. Indeed, we invented multiple features that were never included in the show: We found, for example, that we had to stay away from heavily aerated whitewater – a cool effect to an observer, but one we set aside because the performers couldn’t see through it.

We ran into the same sort of problem with a fog effect that was originally part of the production. The idea was that this large cube of bars with atomized water would appear with a trampoline inside it: After a day of rehearsals, the acrobats complained that they lost sight of the bars because of the fog and the intense lighting. Dragone had needed convincing to try the apparatus in the first place and soon concluded it was too dangerous.

SHOW TIME

All of this effort led to the show’s eventual opening on May 6, 2005. By that date, the systems had been up and running reliably for more than 12 weeks – part of the mandate from the beginning.

“Le Reve” still runs twice daily, five days a week, giving the performers a much-needed two-day break. The show lasts about 75 minutes, which is a grueling schedule for the performers, the production staff and the equipment. Indeed, the entire production is a marvel of physical endurance and technical reliability on all levels.

Through it all, however, the most amazing feature of this extraordinary production is the effect it has on its audiences. I’ve seen it dozens of times, and even as one who understands the technical specifics of the production and knows exactly what’s going on and when, I’m still absorbed every time I see it.

It’s extremely gratifying to witness how audiences new to the experience respond with awe and wonder each time the music comes up, the lights go on and all these amazing systems and gifted performers run through the production’s many phases. Ultimately, I would say that “Le Reve” lives up to its title: It’s very much like dreaming with your eyes open!

AviramMüller is the founder of Karajaal Design Aquatique, a water- experience company based in St-Sauveur, Quebec, Canada, that focuses on the design and engineering of distinctly interactive aquatic venues in which water, lighting effects, fountains and pools are typically part of the package. A multi-faceted artist with an extensive technical background, Müller has worked on three continents through the past 25 years. He has a passion for creating distinct, affordable and ecologically responsible experiences, with a focus on commercial centers and resorts. He is currently working on a textbook on the subject of sculpting with water that will be aimed at university students and graduates in architecture, engineering and the fine arts.