A Base of Comfort

Wanting to soften and humanize the austere appearance of a new facility for homeless families, the benefactors of the Orange County Rescue Mission in Tustin, Calif., commissioned an unusual watershape. The idea pulled watershaper Mark Holden and project manager Jim Bucklin into a whirlwind in which they had to create unique systems to accommodate the world’s largest ceramic amphora – and do so within an extraordinarily tight deadline.

What happens when one of the country’s wealthiest philanthropists provides funding for a truly unique art piece in support of a favorite cause? The short answer is, everyone jumps to make it happen.

That was literally the situation when a nonprofit organization that serves the needs of homeless families received a donation from its largest benefactor to fund construction of an unusual fountain system. The waterfeature, we learned, was to support the world’s largest amphora, which at that time was just being completed by a Danish artist.

Destined for the courtyard of a new facility about to be opened by the Orange County Rescue Mission, the amphora was to be supported slightly above a monolithic granite base with an edge-overflow system and a reflecting pool – and all of it had to be set up rapidly in anticipation of the amphora’s arrival just a few days before the facility was to open.

A conventional project-team approach would never have allowed for the completion of the base structure within the required timeframe. As a result, all participants had to set aside functional distinctions, put their heads together and get the job done. The outcome was a collaborative effort that included some of the most creative problem-solving we at Holdenwater, a watershaping/landscape architecture firm based in Fullerton, Calif., have ever encountered.

A PLACE FOR CARING

All of this occurred in support of a new Orange County Rescue Mission (OCRM) facility called The Village of Hope. Located in Tustin, Calif., it’s something of a revolutionary idea in caring for families in desperate need in that it is the only homeless facility in the region (and perhaps the country) where families are given shelter without separating either parent from their children.

In this case, OCRM decided to use art throughout the facility to create a more pleasant, livable environment – a significant departure from the stark, utilitarian appearance that marks most similar institutions.

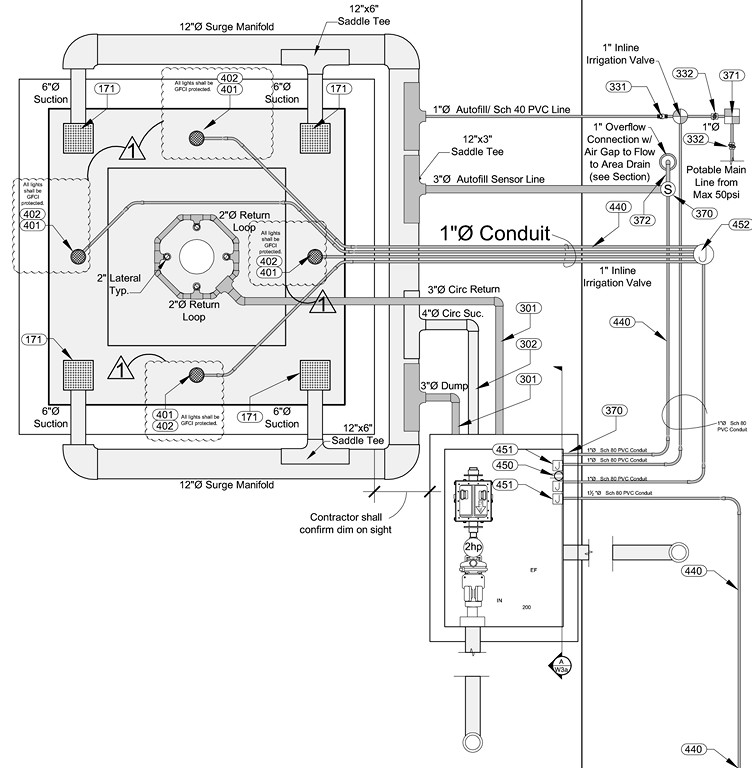

| Organization and clarity were critical in pulling off this project, which began just a month before the anticipated arrival of the huge amphora that was to crown our work. Good schematics and graphics helped everyone on site stay focused as we all set aside conventional roles and came together to get a big job done in a hurry. |

The village is located on a portion of what used to be the El Toro Marine Base, a site perhaps most famous before now for a pair of immense blimp hangars. The rededicated grounds consist of The Village of Hope shelter for families, OCRM’s operations center, a nondenominational church/sanctuary and a medical/dental clinic serving the region’s needy. OCRM’s mission: “Serve the Least, the Last and the Lost of Orange County.”

The organization is magnificently supported by the Ahmanson family, which has for many years devoted a large measure of its philanthropy to helping society’s least fortunate. They were the ones who decided that beauty and art needed to be part of The Village of Hope and were instrumental in making “Art and Altruism” its motto. In joining this effort, we saw the fountain as a rare and special opportunity to get involved not only with a good cause, but also in construction of one of the most unusual features we’d come across in quite some time.

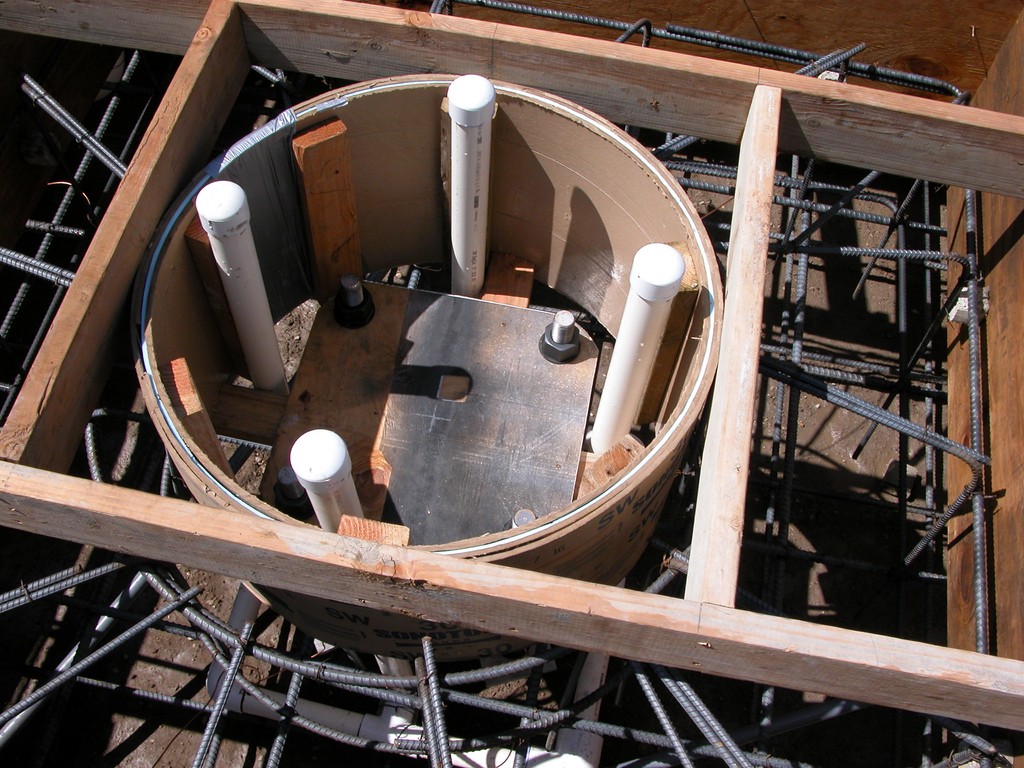

| Once on site, we rolled back the artificial turf and moved rapidly through the excavation, plumbing, steel and framing stages. It’s just a small watershape, but because of the unusual nature of the amphora and some of the specific features that needed to be included, it was actually quite an elaborate process. |

From the start, everyone who participated knew that thinking outside the box would be required – and that it all had to happen in a hurry to make everything ready for a much-publicized opening ceremony. Moreover, the amphora was now en route, out of the artist’s studio and on its way to the Panama Canal, so we had to create an adequate support structure without ever having seen it as anything more than photographs.

There was no wiggle room: As mentioned above, the event had been widely publicized and was significant enough to include the debut of an original symphony commissioned by the Ahmansons and performed by the Orange County Philharmonic.

To say we felt pressure would be an understatement: We all had visions of the guided tours beginning with docents saying, “And here’s where our beautiful, giant amphora would be standing if these bums had done their jobs properly.” But the simple truth was, we had nowhere near enough time to get the work done unless we all put our heads together, forgot about egos and traditional roles and just plain went to work.

Even then, we needed a tremendous amount of luck to stay on track.

CERAMIC CERTAINTY

At the heart of the project is the massive amphora – shaped like an ancient Roman oil container but without the usual handles – by the Danish artist Peter Brandes, who specializes in the creation of very large ceramic vessels. He’d been commissioned to design and shape the world’s largest ceramic container for installation atop a simple fountain, and he delivered big time.

(At this writing, in fact, the amphora is being certified by Guinness World Records Ltd. and appears to be well on its way to being declared the world’s largest.)

| Once the main structure was complete, we moved along rapidly to set up the oversized plumbing system that would provide the surge capacity the system needed, then made all of the connections to the nearly equipment vault. It’s never easy to work with such big pipes; to do so in cramped quarters (and fast) was no fun at all. |

As noted above, the composition is situated in the courtyard of The Village of Hope as its centerpiece and as a beacon for the ideals of the Ahmanson’s philanthropy.

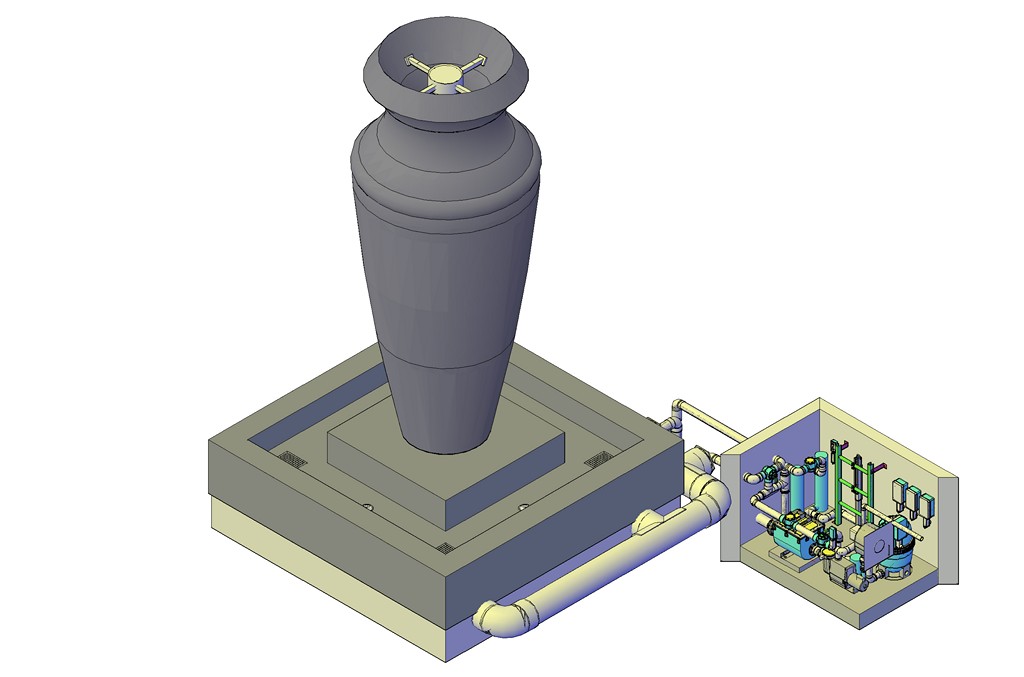

Scenes depicting acts of mercy and charity appear on the amphora’s surface. At its highest, the piece stands 16 feet, four inches tall and is six feet, ten inches across at its widest point. The base is 18 inches above grade, so standing on the pedestal the sculpture is more than 18 feet tall. We were tasked with establishing this base so that, as soon as the amphora arrived, it could be installed and the system started almost immediately.

The base is a 12 foot square that encompasses a raised, six-foot-square pedestal with a hidden stainless steel plate and pole on which the amphora was to be placed in such a way that it would “float” two inches above the pedestal. Water emerges from a concealed void beneath that plate (without touching it), flowing over the edges of the raised platform and down into a large reflecting pool.

All of this base structure is clad in black granite to create beautiful surfaces reflecting the amphora. As a result of the unusual nature of this design and with all of the concrete in place, even the seemingly simple task of tightening the bolts at the base of the stainless steel post and waterproofing them was a something of a mind-bending process.

| As the amphora’s arrival date came closer, we set up the pole that was to support its mass at a point just above the water level. We did all of this without ever having seen the amphora – a fact that added considerably to the stress we all felt as the deadline approached and to the sense of relief that settled in when it fit perfectly. |

Beyond such practicalities, the main trick in this design had to do with hydraulics. We knew that the volume of water needed to wet the granite monolith as a water-in-transit effect fell very close to the maximum we could get to flow from the tiny aperture beneath the sculpture: Only so much water, in other words, could evenly flow from the whole granite cube without causing an unacceptable surge. To make it work with such a precise flow – and no hardware showing! – was amazingly difficult.

We wanted no dry spots, so we needed a flow of 125 gallons per minute to keep the granite surface wet and ensure an even flow across every edge. As a result of concerns about the presence of stainless steel and the amphora’s glazes, we also needed an ultraviolet sterilizing system to avoid the damage that would result from the use of typical oxidizers.

That was all well and good, but the clients also stipulated that they wanted to see relatively little water in the basin – no more than a few inches. This didn’t offer enough surge capacity at about 200 gallons, so we had to add a subterranean PVC loop to increase the capacity and give ourselves the buffer we needed.

The loop consisted of a 12-inch-diameter manifold with more than 300 gallons of capacity. It was tough to install, as would be the case with 12-inch plumbing in any confined space, and it approached comical in the plumbing phase as a small army of people butted heads and elbows and uttered the occasional discouraging word. As luck would have it, the grass around the feature was artificial, so we could work very close to the surface – a big help.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

As we developed our plans, we knew that the artist thought the amphora required no lateral support. That might have been true in his studio in Denmark, but in southern California, we knew that seismic activity could easily take hold of his $250,000 masterpiece and shatter it into a ceramic jigsaw puzzle.

|

Adaptive Thinking One major factor made our success with the watershape described in the accompanying text possible: collaboration. Hours and hours of daily communication with all parties involved were required to confirm and reconfirm every step to be taken – not to mention time spent in innumerable meetings and strategy sessions. Each of us arrived on site knowing that we hadn’t been asked to submit a bid: Instead, we’d been selected as the area’s “go-to team,” and the expectation was that we’d figure out a way to get everything done on time. Our first task was a real puzzler: What would all of this cost? Then, once we’d developed a general sense of how things would proceed, we started running into obstacles. For example, although the team’s steel fabricator and granite installers were quite capable, in both cases we learned that it was likely materials would arrive only after The Village of Hope had opened! It was at this point in the process that we noticed something interesting: Even though we all had confronted the basic impossibility of what we were being asked to do, everyone united in a determined effort to pull it off. We pooled our experience and insights in the name of the project’s success and simply wouldn’t give up. Never had we been in such an environment before: Here were plumbers helping granite installers, landscape professionals helping plumbers and consultants getting their hands dirty, with everyone engaged in problem-solving on an amazingly high level. It was among the most satisfying processes we’ve ever witnessed. In fact, we had the most fun when things seemed wholly impossible. Some had a bit of trouble, for example, with the notion of working extra hours to get through some tough patches. As a team, we spoke with each of these reluctant craftspeople to “enlighten” them about the nature of what we all were trying to accomplish. It worked: Even when faced with sacrificing “free time” to the cause, each participant ultimately went the distance for the project, knowing that their own donations of time were meaningful to the overall success of the facility. The pressure occasionally led to laughter as well. There was much punchy speculation, for instance, that the amphora was actually part of a network of communications devices being set up by extraterrestrials. Although we suspect the Ahmansons might not have fully appreciated the humor, we know it helped us get through some long days and keep our spirits light as the process moving forward. M.H. & J.B. |

That in mind, we installed a 14-inch-diameter, tubular stainless steel column with radial support braces to hold the amphora in place and prevent any teetering. Eventually, we used a 50-ton crane to slide the amphora over the column, which we’d long before attached to the stainless steel base.

The amphora finally arrived, pretty much right on time, and everything was actually in place more than a day early. In totting everything up, we were all astonished by the per-square-foot cost of the feature: Between the amphora and our rapid design, engineering, construction and mechanical work, more than $700,000 was involved – about $5,000 per square foot for a waterfeature!

We wrapped up our work on the Friday before the final event, which was to occur the next day. We all knew at that point that we’d managed to do what we all thought would be practically impossible – and we’d done it with 24 hours to spare, even though none of us had any specific idea it would ever happen.

The party was a wonderful success, OCRM’s coordinators were thrilled and we were all professionally and emotionally satisfied beyond belief – but there was one little mishap.

It seems that during the event, a group of children and a few bright adults came up with the idea of adding goldfish to the basin. In checking out the system afterwards, we found little gold-colored flecks in the industrial strainers. Not knowing what the children had done, it took us almost a week to figure out that we’d found the remains of completely pulverized fish.

| The amphora seems to float just above a skin of water flowing across its granite base – one of the more arresting visual details that set off a ceramic art piece wrapped in reliefs and incised with spiritual writings that speak to the Village of Hope’s work on behalf of local citizens in need. |

The basin and surge loop had no velocity to speak of, so the fish had been free (for a while anyway) to swim through our custom-designed granite grates and into the surge manifold. Unfortunately for them, once they hit the main suction line, velocities increased and whisked them off to the strainer.

It never occurred to us to warn the village’s residents that this was not a fish pond, although with the ultraviolet sterilizer the fish might have done fine if it were not for the way we’d set up the plumbing. That’s a lesson we won’t soon forget – and a mild note of sadness in what was otherwise a splendid performance that filled every one of us on the project team with pride.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, contractor, writer and educator specializing in watershapes and their environments. He has been designing and building watershapes for more than 15 years and currently owns several companies, including Fullerton, Calif.-based Holdenwater, which focuses on his passion for water. His own businesses combine his interests in architecture and construction, and he believes firmly that it is important to restore the age of Master Builders and thereby elevate the standards in both trades. One way he furthers that goal is as an instructor for Genesis 3 Design Schools and also as an instructor in landscape architecture at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona and for Cal Poly’s Italy Program. He can be reached at [email protected]. Jim Bucklin is a professional salesperson and project manager specializing in providing solutions that are environmentally beneficial and make good economic sense. He holds a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of California at Santa Barbara and enjoys making even small contributions to the sustainability of the planet and improvement of our society. At the time of the Village of Hope project, he was an estimator for Richard Cohen Landscape & Construction of Lake Forest, Calif.