Historic Treatments

Local historians claim that the image of Philadelphia’s Fairmount Water Works was the most reproduced of any industrial site in the United States through the first half of the 19th Century – and for good reason. At that time, the facility represented the absolute state of the art and served as a major point of pride for local residents as well as a source of fascination to visitors from near and far.

Throughout its long history, the facility was indeed at the leading edge of water-delivery technology and is now the ideal place to capture and tell the story of the development of environmentalism in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The story begins with formation of the Philadelphia Water Department. Organized in 1799, it is the oldest enterprise of its kind in the country and opened its first pumping station in 1801 to extract water from the Schuylkill River. This was the Center Square Works, located on the site of what is now Philadelphia’s City Hall.

That relatively short-lived first facility was a trailblazer on its own, using some of the very first steam engines ever deployed in North America. But it broke down frequently and was basically a failure, mainly because the primitive boilers had a nasty habit of exploding, often leaving residents without running water for extended periods of time.

A FRESH APPROACH

When the Center Square facility was established, planners chose the Schuylkill, which, in the original Dutch, means “hidden river” – so named because the first explorers of the Delaware River couldn’t find its largest tributary, which was hidden by a broad wetlands area and eluded detection for quite some time.

The water department chose this river because there was already a vigorous debate about the quality of larger, better-known Delaware River’s water and the level to which sewage and effluent from the city had polluted the waterway. In what was perhaps the first discussion of its kind anywhere on the continent, the department ultimately decided that the Delaware was not a suitable source of potable water.

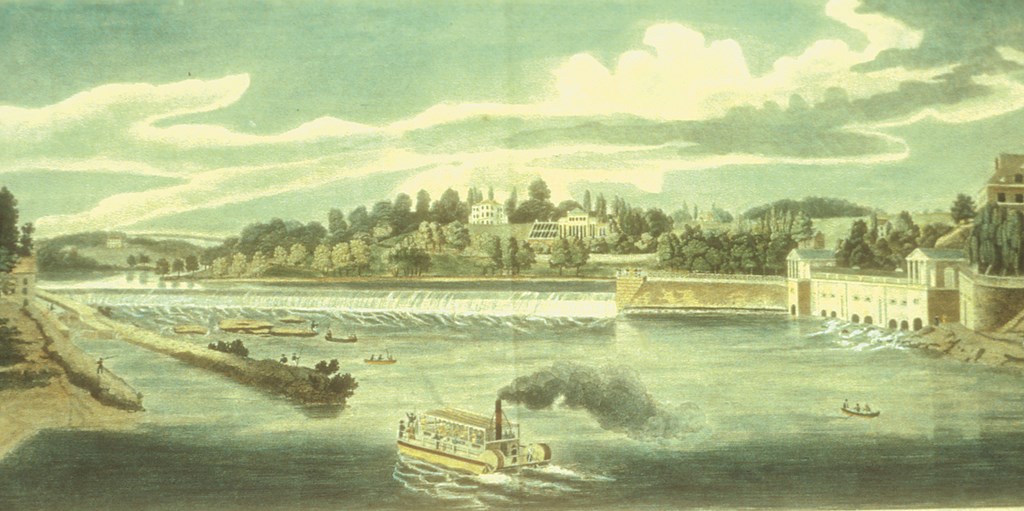

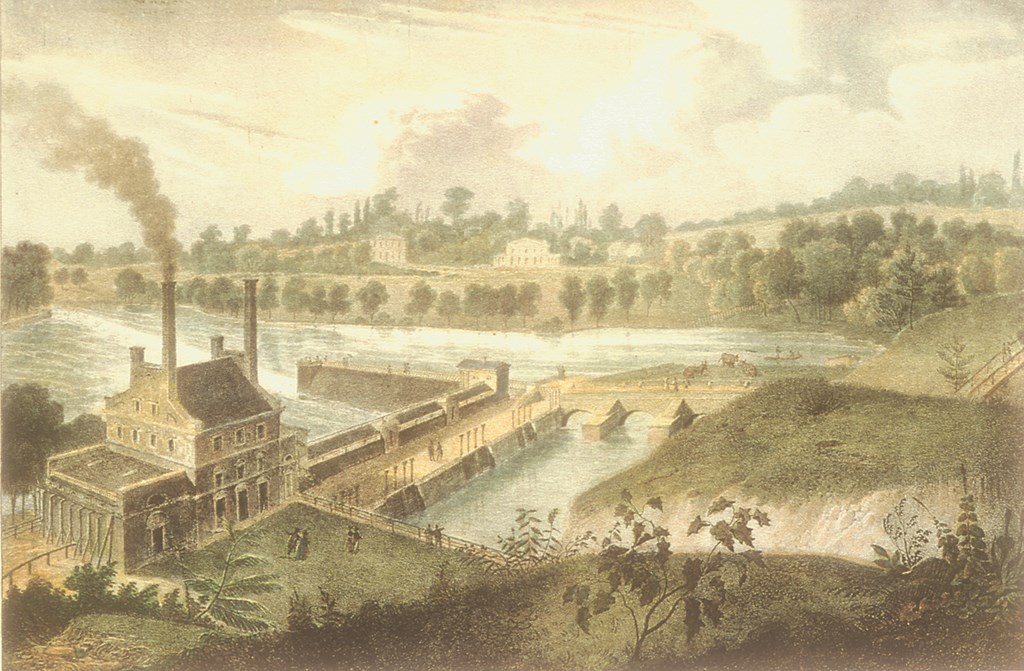

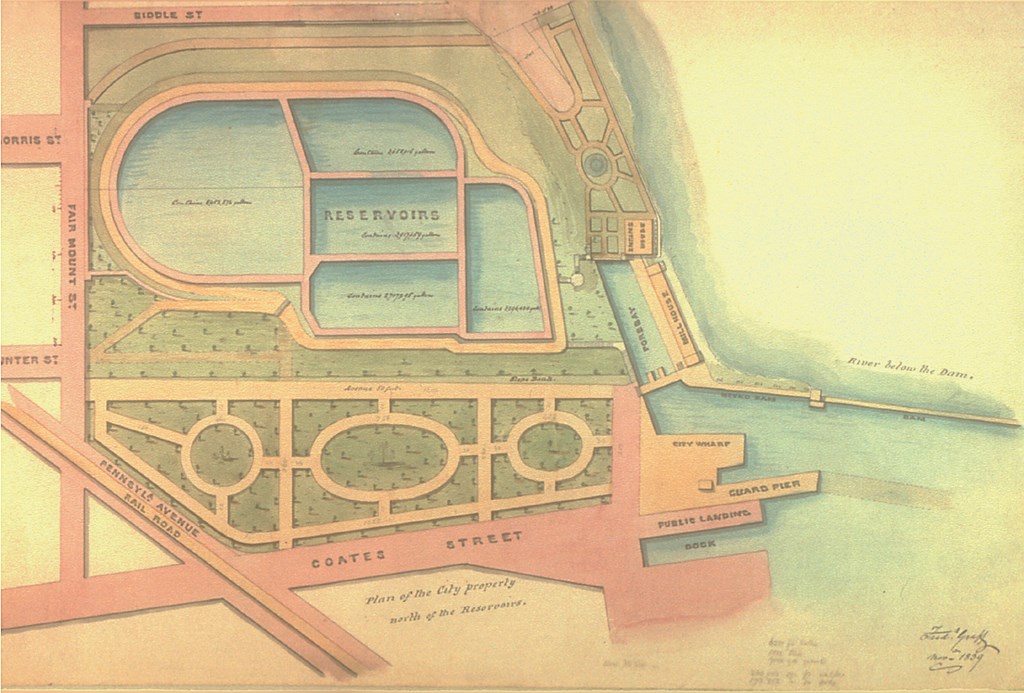

| STORIED SERVICE: The Fairmount Water Works was a source of artistic inspiration through much of the 19th Century, as seen in an early engraving of the Engine House (left), the first structure at Fairmount, by an unknown artist in about 1819. From the start, in fact, the facility was such a point of pride and fascination that every aspect was a subject for illustrators, with the dam seen in an 1821 engraving by Thomas Birch (middle left) and the waterworks featured in an 1822 lithograph by the Ligny Bros. (middle right). The reservoirs (sketched at right) ultimately were replaced; on their site now stands the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Illustrations at left, middle left and middle right courtesy Philadelphia Water Department; at right courtesy Franklin Institute of Science) |

By comparison, the area around the nearby Schuylkill was as yet undeveloped and, as city leader Benjamin Henry Latrobe described it, had water “of uncommon purity.” This soon led to the establishment of the “Faire Mount Water Works” – better known later as the Fairmount Water Works – and initiated a long tale of water treatment, frenzied industrial development, environmental destruction and, ultimately, reclamation.

A powerful local entrepreneur and developer, Latrobe was in town building a bank when the City Council asked him to develop a proposal for delivering water to Philadelphia’s growing population. Using Latrobe’s original plan, the city became the first to construct a publicly owned and operated water-distribution system since the fall of the Roman Empire.

(There were water utilities in Europe early in the 19th Century, but at the time the companies were all privately owned and had been built to supply only certain sections of major cities with water.)

The bold plan was quite a milestone and something of a clarion call: Philadelphia became the first American city to take on responsibility for providing potable water to all of its citizens through a single public entity. This started a powerful trend, during which time a large number of major American cities – including Baltimore, Pittsburgh and Chicago among many others – followed suit and established systems for public water distribution.

(To this day, most large U.S. cities have a public waterworks of some kind, although a great many private water distribution companies operate here and most are owned by European companies or their subsidiaries. Indeed, the Germans and French are leaders in U.S. water-system ownership.)

FINDING A SITE

Latrobe explored available options and settled on an area along the Schuylkill known as Fairmount. The site was perfect: It occupied the highest point adjacent to the city, and it was easily accessible from the river.

Work started with construction of a huge reservoir at the top of the hill and, at the river’s edge, of the Engine House – the first of many waterworks structures and an important visual symbol of the complex even today with its striking Federal-style architecture.

The Engine House had two steam engines for redundancy: When one of the boilers broke down (or blew up), the other was brought on line. (Shrewdly, the planners made the reservoir large enough to hold several days’ worth of water in the event both engines were down simultaneously.) The engines drove double-action, piston-style hydraulic pumps that could deliver a million gallons of water per day to the reservoir.

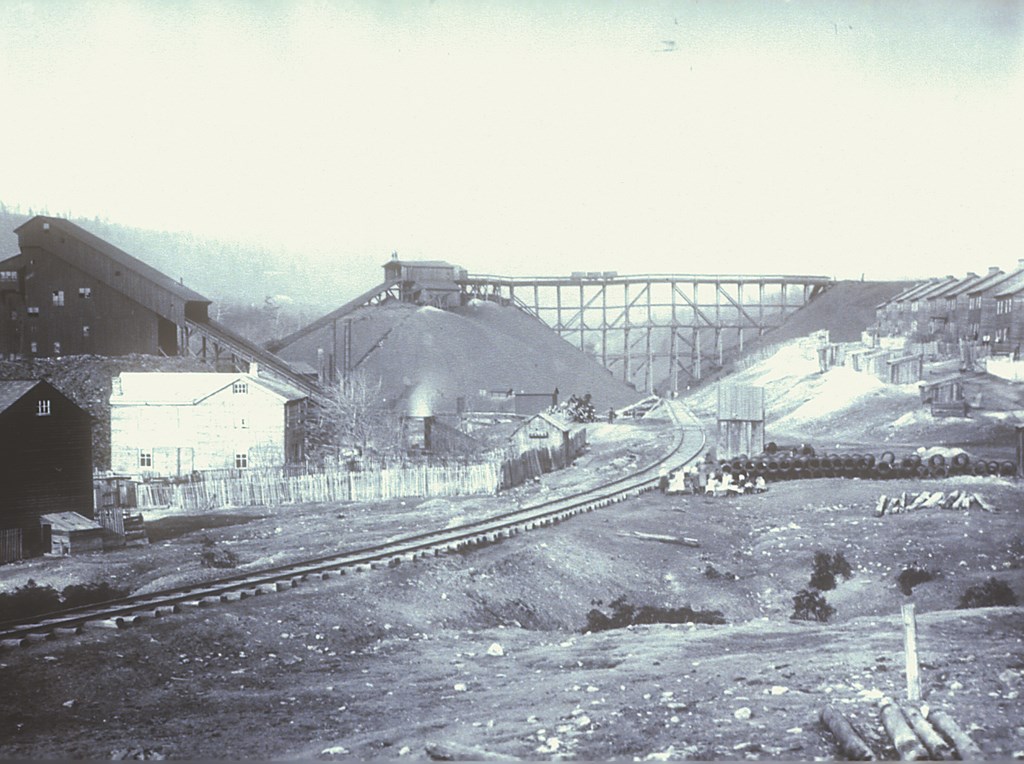

| AMAZING CHALLENGES: The Schuylkill was beset by enormous environmental challenges beginning in the middle of the 19th Century and can only now be said to be approaching a full recovery. Effluent from upstream operations including coal-breaking plants (left, seen ca. 1890) and slaughterhouses (middle, ca. 1921) entered the river unchecked and in huge volumes, and for the best part of a century the river was basically an open sewer (right). (Left and middle photos courtesy City of Philadelphia Archives; at right courtesy Philadelphia Water Department) |

For all of the vision and foresight of the original plan, however, the design was flawed by its dependence on unreliable technology: The steam engines continued to explode, killing several workers through the years. By 1819, city leaders decided to abandon the “new-fangled” steam technology and revert to tried-and-true water power.

By 1822, the city had built what was at the time the longest dam in the world, the main purpose of which was to direct a portion of the river’s flow behind a new waterworks building that would later become known as the Old Mill House. Controlled by a series of gates, the channeled water flowed powerfully over a series of eight massive waterwheels, each 15 feet wide and 16 feet in diameter. The waterwheels and their associated pumps sent water to an expanded series of reservoirs in the upper areas of Faire Mount Park, an area that is now the site of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In all, five large basins served as reservoirs and were replenished slowly by the eight pumps. And flow the water did, with the only “treatment” at that time encompassed in the fact that the water was held in the reservoirs long enough for large particulates to settle.

The new dam and pumping system initiated the Golden Age of the Faire Mount Water Works. From the 1820s through the 1850s, the facility was an icon of American industrial might and a symbol of sophisticated urban planning. And it was indeed an extraordinary infrastructure: The presence of the water-distribution system was a foundation for the explosive industrial and population growth that characterized Philadelphia in that span.

REVOLUTIONARY FORESIGHT

During this era, everything was made in Philadelphia, from locomotives and clothing to equipment for factories, and the waterworks provided water that made it all possible.

An integral part of the waterworks “system” had to do with the development of Fairmount Park itself – although its lack of development may be more to the point. Indeed, one of the truly visionary aspects of the city’s plan was to set aside an expanse of riparian area along both banks of the river to be maintained as unspoiled parkland.

|

Prepared for the Flood As you can see from the accompanying photograph of the facility, there are doors at base of the waterworks building adjacent to the river. As storms make the river to rise to flood stage, the doors are meant to be opened to permit the water to flow into the interpretive center. This meant that everything had to be designed so that the lower areas of the center could be cleared in a matter of six to eight hours in anticipation of a flood (as monitored by the Water Department). We accomplished this by creating bases for the exhibits made of aluminum and fiberglass that can withstand exposure to water. The electronics for the exhibits can all be easily disconnected and carted to a level where they will avoid damage, and some of the larger exhibits are set up with winching systems that will raise them to a safe height. The facility’s ability to flood is both practical and symbolic, demonstrating the idea that humans and nature can coexist, even in an urban setting such as Philadelphia. — E.G. |

The idea was to protect the watershed as a way to ensure continuing water quality, so no commercial, industrial or residential development was allowed in the area, which to this day serves as a 4,000-acre recreation center for city residents. It was, in fact, a great idea that worked right through the first half of the 19th Century.

But efforts to protect the river – one of the first attempts in U.S. history at watershed management for environmental purposes – proved futile during and after the Civil War, when another period of rapid industrialization and population growth upstream of Philadelphia overwhelmed and very nearly destroyed the Schuylkill with pollution.

But in its heyday, Fairmount Park and the waterworks were among places in which Philadelphians loved to see and be seen. Tours of the waterwheels and pumping plants were extremely popular, as was boating and rowing on the pristine river itself. There was even a high-end restaurant on the grounds that overlooked both the river and the proud waterworks.

Unfortunately, for all the visibility the facility garnered for the issue of water treatment, few recognized that an environmental disaster was in the making.

All across the country in the second half of the 19th Century, cities such as Philadelphia simply lost the social will to maintain and control water quality. Large industries of the day wielded tremendous political and economic clout, and any attempts to force them to stop polluting the country’s major rivers were roundly rebuffed. During this time, rivers came to be used (and seen and smelled) as open sewers, and the water became increasingly foul and polluted.

Even the bucolic Schuylkill, once teeming with fish and rich riparian shores, became fetid and, at the worst of times, even deadly.

PAINS OF NEGLECT

During the 1890s, a typhoid epidemic hit Philadelphia and killed thousands of people annually. Over in Chicago, a similar sequence of outbreaks killed even more. Cholera and other waterborne diseases were also profound challenges to public health at that time, and Philadelphia was among municipalities facing a true crisis.

The city responded with technology, using filtration for the first time in a large-scale water-delivery system. The slow sand/gravity filters proved effective in removing large quantities of solid waste from the water, but they took several years to complete and come on line. When they did, however, deaths from typhoid and cholera dropped substantially. And by 1912, the city began chlorinating the water – at which point incidents of waterborne disease all but ceased.

| INCREDIBLE COMEBACK: Concerted efforts through the past 100 years have brought both the Schuylkill and the Fairmount Water Works back to good form. The construction of wastewater-treatment plants (left) diverted upstream and urban waste away from the river, and eventually work began toward restoring the waterworks structures (middle) as a center for education and research. The goal has been to make the river pristine once again – a complete resource for the community and its recreational needs (right). (Photos courtesy Philadelphia Water Department) |

Water treatment now meant that polluted river water could be made safe. Although nobody would claim much joy at the aesthetics of the water, it was possible for the first time in decades to take a drink of water from the tap without risking life and limb. Ironically, this also meant there was no immediate public concern for the rivers themselves, and they went almost completely unprotected through the first half of the 20th Century.

It is difficult to describe the awful conditions that had beset the once-pristine waters of the Schuylkill and dozens of rivers like it through this period. Many species of fish, birds and other animal life that depended on these rivers either became extinct or were all but wiped out. But steps toward reclamation of Pennsylvania’s rivers began in 1904, with the establishment of the state’s health department, which had a primary mission of dealing with wastewater and started its work by requiring all cities in the state to submit a plan for wastewater treatment – this at a time when waste was still being dumped freely into the rivers.

Philadelphia submitted its preliminary plan in 1905 and by 1914 had begun devising a system of interceptors to capture wastewater and route it to three treatment plants. But sewage never has been politically sexy, so full implementation of the plan was stalled until after World War II, when the city taxed its citizens to pay for a sewage-treatment system. With funding in place, the city turned implementation over to the Philadelphia Water Department, a wise choice in that this was the organization with the largest stake in cleaning the river.

By 1957, the plan originally developed in 1914 finally came into service, and in subsequent years the water quality of Philadelphia’s rivers improved dramatically.

THE ROAD TO RECOVERY

Nonetheless, the waters of the Schuylkill had been badly contaminated and, even though human waste was no longer a factor, industry was still dumping an astonishing mélange of contaminants into the river. It wasn’t until 1972 and the passage of the Clean Water Act that rivers had a shot at returning to something resembling a natural state.

By 1984, Philadelphia had implemented a secondary water-treatment system using microorganisms to treat waste in water being discharged into the rivers, and both the Delaware and the Schuylkill have been profound beneficiaries – and begun their returns to healthful beauty.

Today, we’ve come almost full circle: More than 40 varieties of fish have returned, including Striped Bass, American Shad and Hickory Shad. All sorts of fish-eating birds and terrestrial predators have returned as well, and the rivers simply look better, even beautiful. Today, in fact, 80% to 90% of the pollution that actually makes its way into the river is the result of storm runoff, a problem that afflicts a great many American cities.

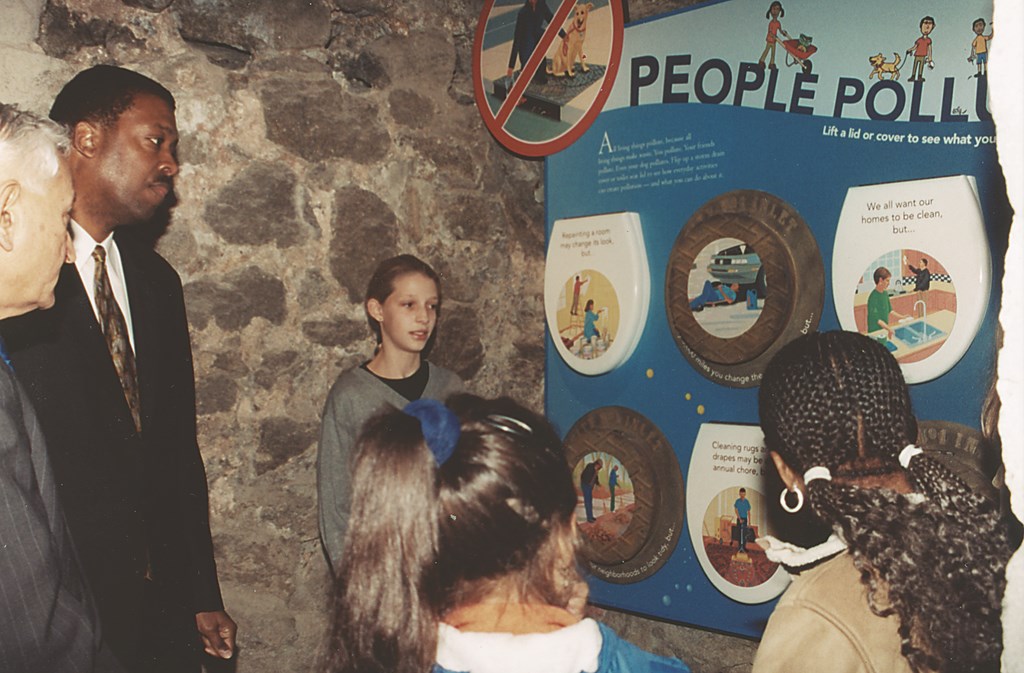

| EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE: In addition to housing research labs dedicated to study of water-quality issues, the old waterworks structures also host an interpretive center designed to educate current and future generations about the preciousness and fragility of natural water resources. The facility itself is largely seen in its original rough-edged condition, but the displays are strictly state of the art and reflect the latest available information on pollution prevention and watershed management. (Photos courtesy Philadelphia Water Department) |

As for the waterworks, it carried on as something of a public attraction even after it began a gradual decommissioning process in 1912. A large aquarium was set up in a building that became known as the New Mill House and drew millions to see a wide variety of salt and freshwater fish before it closed in 1962. A public swimming pool was established on the site in 1963, but it was destroyed in the flood generated by Hurricane Agnes in 1972.

Much of the facility had fallen into disrepair before Agnes came along. The hurricane only accelerated the process of decline to a point where the facility was little more than a ghostly eyesore along the riverbanks.

A call for rehabilitation was finally heard in 1974, when the Philadelphia Junior League challenged the Water Department and the Fairmount Park Commission to restore the buildings and put them back to public use. The plan gained public acceptance through several years and gained a strong level of added support in 1998, when the Fairmount Parks Commission formed the Fund for the Water Works.

At that time, a huge fundraising effort was mounted with cooperation from a variety of public and private organizations including the William Penn Foundation, the Philadelphia Port Authority and Pennsylvania’s Environmental Protection Agency. The federal government participated as well: Initial design for the exhibits at the new interpretive center was made possible from a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

A PLACE TO LEARN

The interpretive center is both an homage to the waterworks’ history and a rallying point for future environmentalism. All of the interior walls have been left in their original, unfinished condition, while the buildings’ exteriors have been beautifully restored to their original glory. Inside are 40 mostly high-tech, interactive exhibits that tell the story of watershed management in the area and educate visitors in the fundamentals of aquatic and environmental science.

The first exhibit starts with a molecule of water and shows how all living creatures from dinosaurs to fish and human beings have consumed the same molecules of water that have been on the planet since time began. There’s also an exhibit that demonstrates the effects of precipitation, runoff, evaporation, percolation and transpiration into the atmosphere.

Fully a third of the exhibits are focused on watersheds and how land is used – and how those uses affect water quality in rivers and other surface-water resources. There’s a display on tidal estuaries that is essentially an educational watershape with a model of the old waterworks and dam that shows the six-to-eight-foot tidal variation in the level of the river. This real-time exhibit defines the water levels relative to the waterworks and the dam, which can be seen right outside the window.

| COMMUNITY PRIDE: Rather than blighting the Schuylkill waterfront, the restored Fairmount Water Works now stands alongside picturesque boathouses as a gleaming monument to pioneering 19th Century technology of urban water distribution. The river itself offers rolling testimonial to the power of environmentalism to salvage and preserve our waterways. (Photos courtesy Philadelphia Water Department) |

Yet another exhibit, this one provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, shows the way runoff operates in a variety of settings, including a seaport and an urban area as well as wilderness and farmland areas. Another shows how activities in the home pollute water and how that pollution is removed before the water returns to the river.

Two local firms, Steve Feldman Design and Talisman Interactive, designed the exhibits. In both cases, the work they’ve done is both imaginative and amazing.

The buildings themselves have been beautifully restored and remodeled under the guidance of local architects at Mark B. Thompson Associates and brought up to date with office space, classrooms and a lab that can accommodate more than 30 scientists conducting research on water-quality issues. For the most part, the buildings still have their original rough edges, with walls and surfaces telling their own stories about the development of the site – including the long subterranean corridor built in 1812 to speed worker passage from the boilers to the pumping rooms. Many of these original features have been left in place and are now surrounded by modern additions.

The park itself includes a number of waterfeatures in the forms of fountains and natural springs that have long been a key part of the experience of visiting the property. A highlight of the south garden of the waterworks is the soon-to-be-restored Marble Fountain, which was installed in the 1830s and originally featured 40-foot plume driven purely by gravity and head pressure.

HIGHER PURPOSE

Our main mission with the facility’s exhibits is showing people how rivers and watersheds work – how each and every one of us fits in with the systems, how we influence water quality, how the watershed works and how we can all help sustain or improve it. This sort of public education is particularly important in areas such as the water-rich northeast, where the resource is abundant and people have historically taken a ready water supply for granted.

There couldn’t be a much better place to tell this important story, given the central role the Fairmount Water Works has in the history of water quality in the region. It’s also still one of the few places in the city where you’re right on the river in a parkland setting and can see hunting ospreys, jumping fish and the river running muddy after a big rain.

The facility does important work with a variety of city entities, including the Building Department, which now encourages use of porous hardscape to minimize runoff, and the school district, which is mounting a campaign to encourage “green buildings” in which runoff from the rooftops and storm gutters is directed into drainage areas for use in irrigation systems or flows to marshlands or retention and percolation basins.

The park itself has never been more popular. The adjoining boat house accommodates more than 2,000 rowers and their sculls per day, and there’s an eight-mile running circuit that passes the Water Works and is always packed with walkers, runners, bikers and skaters. All of these people see in very direct ways how river and water management have an influence on their daily lives.

Although the work of protecting our rivers will never be done, it can be said that the story of water treatment in Philadelphia and countless other cities is now one of developing ways to serve people and nature.

Ed Grusheski is general manager of the Public Affairs Division of the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD). He previously served as an educator at Boston Children’s Museum, the New Jersey State Museum, Philadelphia’s Civic Museum and the Port of History Museum and was Director of PWD’s Water Works Interpretive Center before taking his current position with the Department. Educated at Boston Latin School, Georgetown University and the University of Pennsylvania, Grusheski lives in Philadelphia and serves on many task forces and committees, including the Department of Environmental Protection’s Coastal Zone Management Steering Committee, the Schuylkill River Heritage Corridor Urban Gateway Task Force, the PWD Water Quality Education Committee and the Fairmount Park Commission Fund for the Water Works. He is also president of the Oliver Evans Chapter of the Society for Industrial Archeology and a Trustee of the Abraham Lincoln Foundation of the Union League of Philadelphia and serves on the Strategic Planning Committee for the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary.