The Unfolding Garden

As adults, we too often forget one of the great joys of childhood – the sense of wonder and discovery we experienced when we first saw the ocean or flew in an airplane and the world opened and unfolded before our very eyes.

As designers, I believe we similarly forget about the excitement that comes with discovery. Too often, we lay out beautiful lines and incorporate interesting and unusual plant and hardscape material for everyone to see all at once. The work may be beautiful, but it leaves little or nothing to the imagination and offers no surprises.

I can’t help thinking how much more our landscapes, public and private, would be savored if they were to be explored and discovered bit by bit. This is especially true for spaces containing watershapes, which by themselves lend interest and drama to almost any space: The magic of water can (and I believe should) be exploited by concealing it at first and then revealing it in a way that gives the viewer a brief moment of visual revelation.

To see what I mean with respect to watershapes and waterscapes, let’s explore an approach that makes seeing everything immediately an impossibility. Instead, this approach offers glimpses that tantalize and intrigue – and can be seen in the work of thoughtful garden designers who’ve manipulated sights and sounds around the water’s edge to lend these spaces a transcendent sense of discovery.

AURAL INVITATIONS

Consider the experience of being drawn to a watershape not because you can see it, but because you can’t. Ever heard a sound that so entranced you that you felt compelled to discover its source? When you work with moving water, you have the opportunity to set up that experience for clients.

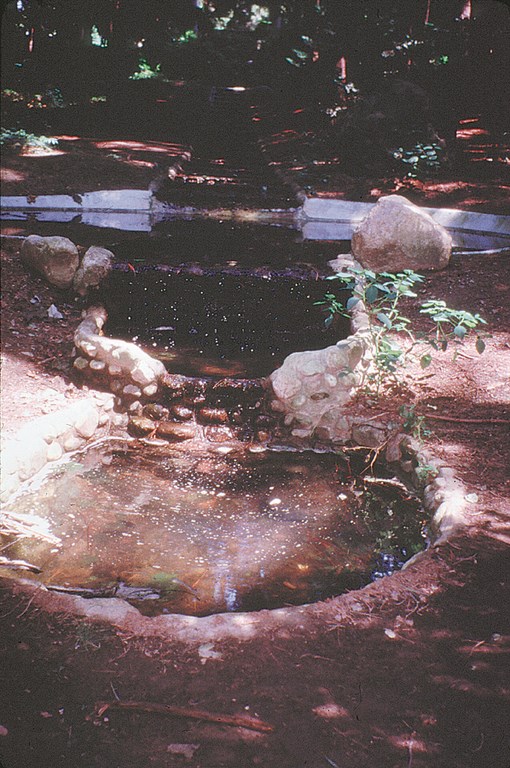

Here’s a striking example: Near the education building at Strybing Arboretum in San Francisco is a relatively narrow tropical garden that backs up to a wall and has a very narrow path through it. As you walk along the path, you hear a faint bubbling sound. Not until you come to the end of the path do you discover a tiny pool with a bubbler in the middle.

Even though you have been listening to this subtle sound, however, you might easily miss the pool because it is almost completely surrounded with rocks and verdant plantings (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 |

Or sometimes the sound itself is the surprise at the end of a quiet path. At Cranbrook Gardens in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., an old estate has been converted into a public garden with many wonderful elements. One of them, the Greek Theatre, is approached by way of a long woodland path. The attractive force here is not sound; rather, it is the tall Greek columns that surround a becalmed, rectangular pool.

|

Swimmin’ Holes The designing and placement of swimming pools in landscapes can be problematic. First of all, they tend to be big. Second, some municipal codes require that they be fenced for safety reasons. But neither of those factors means that one of them has to be seen the instant you look out of the back of the house – at least not from the first floor, anyway. When swimming pools are fenced, there is normally one gated entrance. If you think about it, even the entrance does not have to be apparent as long as the path leading to it is obvious. So consider surrounding the pool with a garden full of tall plants including trees, large shrubs, grasses and perennials. World famous designer Wolfgang Oehme has a swimming pool in his own backyard that is totally hidden from the patio by his “jungle.” It seems to me that, not only do we contribute to the thrill of discovery by designing this way, we also enhance the swimming experience by adding a sense of immersing ourselves in nature. After all, the very first swimming pool was a natural body of water surrounded by trees, shrubs and grasses as well as birds and butterflies. Who says the main thing you have to see when floating in the water is the back of the house? In Rotterdam, I visited a private city garden that is essentially a long, relatively narrow rectangle (left). About halfway toward the back of the property, you catch sight of the rest of the garden through a frame of two large trees sited at the edges. What you see to the rear and center right is a horizontal row of four-foot-high evergreens that intersect a shrub border on the far right. Parallel to the shrub border (but at a 90-degree angle to the evergreens) are some blue spruce. In the neighboring space is a chair, which implies that you might find a patio in the space bordered by the Spruce and the evergreens. What a surprise, then, to find not a patio, but a full-size swimming pool! In addition, the right side of the pool is bordered not by paving, but by a planting bed full of conifers and deciduous shrubs that comes right up to the edge of the pool (right). Swimming pools can be hidden by grading as well as plants. A client of mine has a pool that cannot be seen from the street because it sits below a four-foot wall that has landscaped beds on top of it and then a sloping lawn above those beds up to the street. The pool cannot be seen from the drive down to the garage either, because that area has a trellis wall covered with vines. The pool can only be glimpsed from the kitchen window through the canopies of trees that mostly screen it from plain view. Another way to make a pool or pond become a revelation is through manipulation of the land. If the client has a property with hills and valleys, all to the good. If not, however, the land can be graded to create a depression or a streambed. Then, with careful selection of plant material, you can create a short or long expedition leading to the hidden watershape. I don’t know if the University of California’s Asian Garden in Berkeley was created on natural terrain or constructed terrain, but the end result is a great joy, with a pool at the bottom of several slopes that can be viewed from several vantage points. When you see it from the top of the highest path, you’re drawn closer and closer until you reach the pool itself. But to get there, you must travel along a path and through a plethora of incredible rhododendrons while catching brief glimpses of the pond along the way. To be sure, we’re generally not given that much space to work with, but principles of screening and grading can certainly be applied on a smaller scale to bring a sense of discovery to just about any swimming pool in almost any client’s backyard. – B.S. |

Once the visitor comes to the end of the path and stands in this area of the columns and the pool, he or she picks up the sound of water but has no immediate idea as to its source. Moreover, that sound will vary, depending upon the amount of rainfall at the time, from faint drips to a rushing cascade.

With further exploration, the observer finds, on a wooded slope behind the theatre, a series of perhaps 30 wide steps over which rainwater descends until it reaches two small pools, one below the other (Figure 2). This cascade was built before the era of re-circulating pumps, but if the idea were to be copied by a contemporary designer, the sound could remain a constant (and equally variable) invitation to further exploration of the garden space.

| Figure 2 |

In my view, we designers don’t make sufficient use of this element of surprise. Frequently, our clients will tell us they want to see the ornamental pool or pond from the house. But must it be seen immediately from the paths that visitors take from the front entrance around the house to the back where the pool is?

Why can’t we lead these visitors on a journey through interesting plant material on the way? And then, as they near the pool or pond, why can’t we screen it in some way so that the watershape comes as an unexpected marvel? Why do we feel that we have to have visual accessibility from every angle?

PATHS TO BEAUTY

The development of a sense of discovery begins to take flight when you think about questions like the ones I just posed and begin to understand the value of things like screening.

An excellent example of screening is a garden in Baltimore – a collaboration between the client and the firm of Oehme & Van Sweden. Here, a small ornamental pool, contiguous with a patio just off the back of the house (Figure 3), may be approached in one of two ways, neither of them direct: You can walk around the house past a hedge of tall conifers to a path that cuts through two of them and then discover the pool. Or you can come from the opposite direction on a path that meanders beside a Lagerstroemia (Crape Myrtle) and be enticed to look through its foliage and exfoliating limbs as through a veil. This is an adventure rather than a mere sighting.

| Figure 3 |

Back at Strybing Arboretum, there is a rather large pond mostly surrounded by conifers and a wide walking path. At one end of the pond, however, you can duck under and through branches of two enormous conifers onto a path of sand and stone steps and almost imagine yourself on a small beach (Figure 4). If you were to approach the water from that end first, the pond would come as a complete and delightful surprise.

| Figure 4 |

In both of these cases, it’s about the designers thinking through and controlling access to the watershape at the end of the path. Yes, a direct approach might have worked well in either case, but the profound impression and experience that comes with the unfolding of the scene would be entirely lost.

|

Traveling for Inspiration It takes an investment of time and money, but from my perspective, there’s no better way to learn about styles and principles of design than by breaking away from your usual environment and seeing a bit of the world. For my part, the inspiration to create a sense of discovery has come in large measure from visiting and studying English and Continental gardens. These journeys have had a profound impact on my designs: Without the stimulation of seeing other designers’ solutions and creativity, it’s all too easy to forget that the obvious approach may not be the best. In my travels, I have learned to use the concept of the large plant by the curving path to hide some of the garden in many of my designs. I have also designed some diagonal gardens on barren rectangular properties, using large plants on the points to disguise part of the landscape. I use the concept of the see-through plant to gradually reveal a vista or vignette as well. The best of it is that none of these ideas are expensive: It’s all about how you perceive and use the space and add value to a design without bankrupting the client! – B.S. |

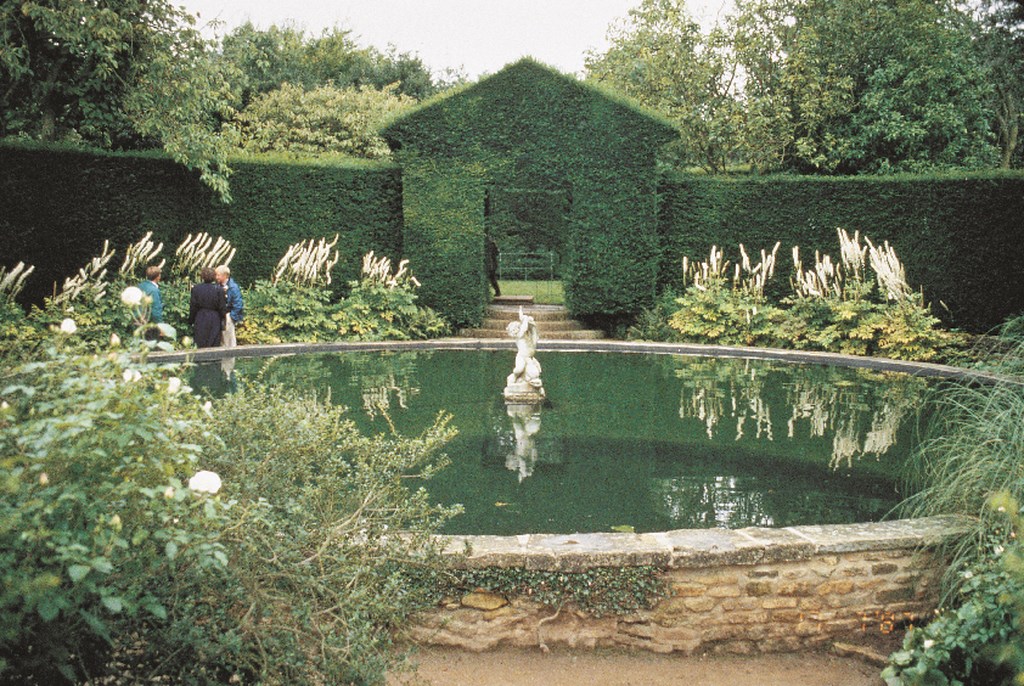

English designers have been attuned to the importance of this principle of surprise for many years. At Hidcote, now a National Trust Garden, owner Lawrence Johnston converted a piece of farmland into a series of garden “rooms” early in the 1900s. As one treads a brick path and enters the fuchsia garden, part of a pool and a statue in it can be perceived just beyond in another space that is mostly screened by sheared conifers (Figure 5A).

This glimpse tantalizes the observer, who then proceeds down the path to the Bathing Pool. Even then, as one enters this room, the view of the pool is partially obscured by the ring of Cimicifuga racemosa (Black Snakeroot) on the outer edge of the path around the pool (Figure 5B).

| Figure 5A (left) and Figure 5B (right) |

Another English designer, Rosemary Verey, is a firm believer in vistas and has used that concept very cleverly at Barnsley House to tempt the visitor to discover the pool in front of the Greek temple that she and her husband rescued from demolition. Standing at the end of a grass path, flanked on both sides by long mixed borders, you see the temple with tall iron gates on either side and tall tropical looking plants just within (Figure 6A).

| Figure 6A (left) and Figure 6B (right) |

At that point, it’s not clear whether there is a small pool in front of the temple or whether you’re looking at a bed of groundcover. Only as you approach the vessel can you distinguish the water and the water lilies therein (Figure 6B).

SUNKEN TREASURE

Naturally, there’s more than one way to build surprises into landscapes.

At Great Dixter, England, home of the noted plantsman and garden designer Christopher Lloyd, the “bones” of the garden were designed by Edwin Luytens and Christopher’s father, Nathaniel. A tall evergreen hedge serves as one of the walls of the Sunken Garden; an arch, carved into the hedge as a doorway, provides a partial view of this “room” (Figure 7A).

Simply passing through the arch does not allow you to see the pool within: It merely allows you to see that there is a lawn surrounded by mixed borders and that within the lawn are three levels. Not until you are fully inside this garden room can the sunken pool be seen in all its beauty, because it is edged on the entrance level with a three- to four-foot-tall mixed planting of perennials and ornamental grasses.

As you come closer to the pool and then descend to the lower levels, you’re better able to appreciate the design of the pool itself, the planting of the stone paving around it, and the planting of the stone wall surrounding the paving (Figure 7B). The complexity of this design can provide multiple levels of inspiration for a watershape so long as the designer remembers that sunken gardens should not be fully appreciated until seen at close hand.

| Figure 7A (left) and Figure 7B (right) |

England, of course, has the luxury of old estates and relatively mild temperatures. In many parts of this country, designers need to be a bit more innovative to make the elements of surprise work year ’round – and sooner rather than later. If our clients cannot afford to buy mature evergreens for hedges or build walls of stone or brick, we can use ornamental grasses or shrub roses or prolific vines on trellises as walls.

At The Land of Nod, a small private estate near Kiftsgate, England, the present owner’s father established an English version of a Japanese garden. Here, one enters through a torii arch covered with vines and follows a curving path composed of stepping stones set into the grass (Figure 8A). This path leads to an open expanse of lawn into which is set a pond surrounded by Japanese Maples and several other kinds of vegetation that mostly obscure the edges of the pond and also hide it from the other side (Figure 8B).

| Figure 8A (left) and Figure 8B (right) |

Again, full appreciation comes only when you are up close to the watershape. The beauty of the design has many levels, not the least of which is the way the designer has controlled the observer’s pathway to that closer view with screens and plantings.

DISCOVERY ON GRADE

We can also work with the land itself by creating terraces and paths that take the viewer from one level to the next – and by placing watershapes on one or more of the terraces. With judicious selection of plant material, the watershapes themselves would not be apparent until the viewer was quite near.

|

Designed for Drama Observation of the world through which we travel, near and far, stimulates our minds and helps us think creatively. Once, for example, while riding on a cog railway in Switzerland from Interlaken up to the Schynige Platte, an alpine botanical garden, I occasionally caught glimpses of one of the lakes below. The view was frequently hidden by tall conifers and other shrubs and trees as well as by perennials and grasses that grew along the tracks. When the view was unimpeded, the sight of the lake was a gift. Such should be our intent when designing watershapes into landscapes: Let them be gifts rather than givens. Frequently, ornamental pools are either set into an obvious patch of lawn or made part of a patio. Why not border these pools on one, two or three sides with perennials and ornamental grasses that are at least as tall as eye level (or even a seated eye level) so that the pools cannot be seen immediately? Instead, let the viewer be pleased initially by the beauty of the plants, later to enhance that pleasure by the discovery of the pool! – B.S. |

There’s a private garden in the Boston area that employs this strategy. The house sits on the lowest level of the terraced property. Outside the back of the house is a simple formal garden; at the far end, you are drawn forward by lawn and steps.

These steps ascend between a woodland garden on the outer edge of the property and a meandering stream on the inner side. This stream, which can only be glimpsed from time to time through closely planted, water-loving perennials and shrubs, also flows under the steps to the other side and then seemingly drains into the woodland garden.

As the viewer nears the top of the steps, a new world is seen through a delicate iron arch. This new world features an undulating swimming pool with planting pockets that come right up to the water’s edge – with more beds just on the other side of the unevenly spaced width of the surrounding paving (Figure 9). As you wander around the pool, in other words, you are also strolling through a garden.

| Figure 9 |

This strategy of terraces and steps to pull the gardener or the visitor through a sloping landscape has also been used in Atlanta at Hosta Hill. Here, a hosta lover and collector built a zigzag series of brick steps with landings interspersed. Beside one of the landings is a small pool that can be seen neither from the bottom nor top of the steps but only from a close observation point (Figure 10). The element of surprise increases our appreciation of this unexpected watershape.

| Figure 10 |

Of course, how you achieve a sense of discovery depends on many, many factors including size of the space, the desires and tastes of the client, the nature of the watershape and the plantings you are using. The key is to be ever on the lookout for opportunities to conceal and reveal the beauty you’re so painstakingly working to create.

When you do, you may be surprised by the profound effect it has on the work and all of those who enjoy it for years to come.

Bobbie Schwartz is a landscape designer, consultant, lecturer and writer – professions that have made her well traveled in pursuit of excellence in garden and watershape design. She founded her full-service design business, Bobbie’s Green Thumb, in 1977, and her residential, institutional and commercial designs have been recognized by awards from the Perennial Plant Association, the Ohio Nursery & Landscape Association, the Ohio Landscapers Association and the Cleveland Botanical Garden/ASLA. Schwartz participates in several trade associations on the national, state and local levels and currently chairs the Certification Committee for the Association of Professional Landscape Designers.