The Uncommon Garden

For more than two decades, watershape designer and builder Ryan Oakes has leant his talents to the ongoing creation of a place known as “The Uncommon Garden” located in Chapel Hill, N.C. Here he takes us on walk through the history of a space so unique, whimsical and imaginative that it defies convenient description – and, yes, it does feature dragons.

By Ryan Oakes

The words “unique” and “awesome” are badly over used these days, but when describing a place in Chapel Hill, N.C known simply as “The Uncommon Garden,” both fit perfectly. It is literally one of a kind and does inspire awe — along with whimsy, imagination, curiosity and I dare say, happiness. Some have called it a “surrealistic Zen Garden.”

I just know it’s one of the most amazing works of personal expression in a landscape that I’ve ever experienced. There truly is nowhere else quite like it.

I became involved early in the garden’s development in 2001, back when I was building fountains, ponds and water features of all types. I was contacted by a couple who needed help with a broken waterfeature. The wife, a hedge-fund manager had found me through mutual friends from my college days, her husband is well-known local artist, Rick Hermanson.

I repaired their waterfeature, and we really hit it off in the process. Hermanson mentioned that he was working on an unusual project nearby and asked me if I’d meet him at the site to have a look at what they were doing.

Little did I know it was the start of a journey that would become an ongoing part of my life, and one of the most liberating undertakings as a designer and builder.

AN UNEXPECTED JOURNEY

The client had hired Hermanson to help him build what was loosely being called a Zen Garden. Hermanson had little masonry or landscape experience – that’s where we would come in – but he knew what a garden should feel like. It was clear from the start that these two guys were taking an extremely open-minded approach to developing the space.

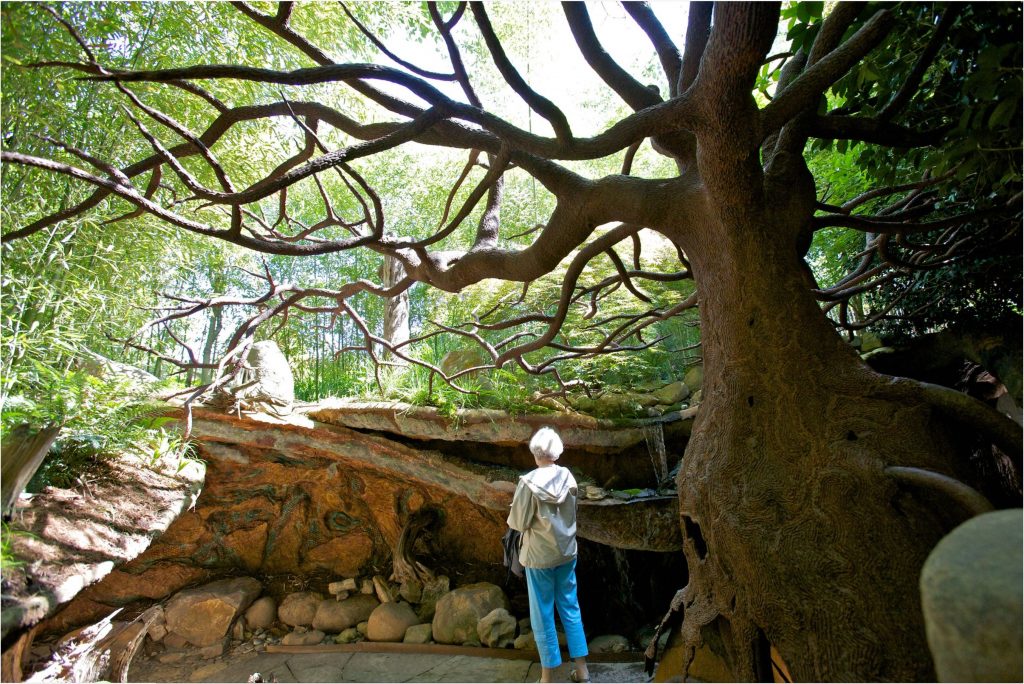

Even though it’s only a half-acre, the property feels much, much bigger. That’s largely because the garden is designed as an unfolding journey where you discover landscape in vignettes and ever-shifting views. Hermanson was creating garden rooms and niches, with no open expanse, yet with raised vantage points where you can see the whole thing like you were hovering over it in a mothership.

In the true Japanese Gardening ethos, it’s about the journey not a single destination. It’s an unfolding experience, which was the guiding principle from those earliest discussions through the entire process.

And, did we ever get creative in populating the journey you take. There are almost countless details, big and small, literal and abstract, and often fascinating sculptural and landscape ideas, brought to fruition by the many artists and artisans who have contributed their own creativity and skills over the many years.

In each area, there’s an almost infinite level of detail featuring a broad spectrum of blended materials, sculpture, waterfeatures and seemingly countless creative ideas. You’re always discovering something new in every nook and cranny, rewarded by something unexpected at every turn.

While the concept is largely that of a Zen Garden based on Japanese Garden design principles, there’s also an element of whimsy and use of thematic elements drawn from a universe of influences. Many of the features hold a strong appeal for children and probably more accurately to the child that lives on in each of us. Above all else, the place is uncommonly fun.

AROUND THE WATER

Consistent with our guiding design principles, water is at the heart of the garden; and, in this case, it’s a big heart, indeed. Hermanson initially asked me to build a water garden that would work as the spatial hub of the garden.

I had been studying Japanese gardening since I was a kid, traveled to Japan and, in college, started studying it formally. One of the guiding principles is that your orchestrating movement through the garden. It’s also involves playing with planes and sight lines. We see that nowadays in some swimming pool designs where you bring water up to the highest reflecting point, with perimeter overflows and vanishing edges.

That overall approach informs how I consider the ways in which water influences your experience in the environment and perceive the space. For example, rocks around a water garden should not appear to be floating on the water’s surface, because that’s distracting. Instead they should be embedded in the edges and landscape surrounding the water, as you would find in nature.

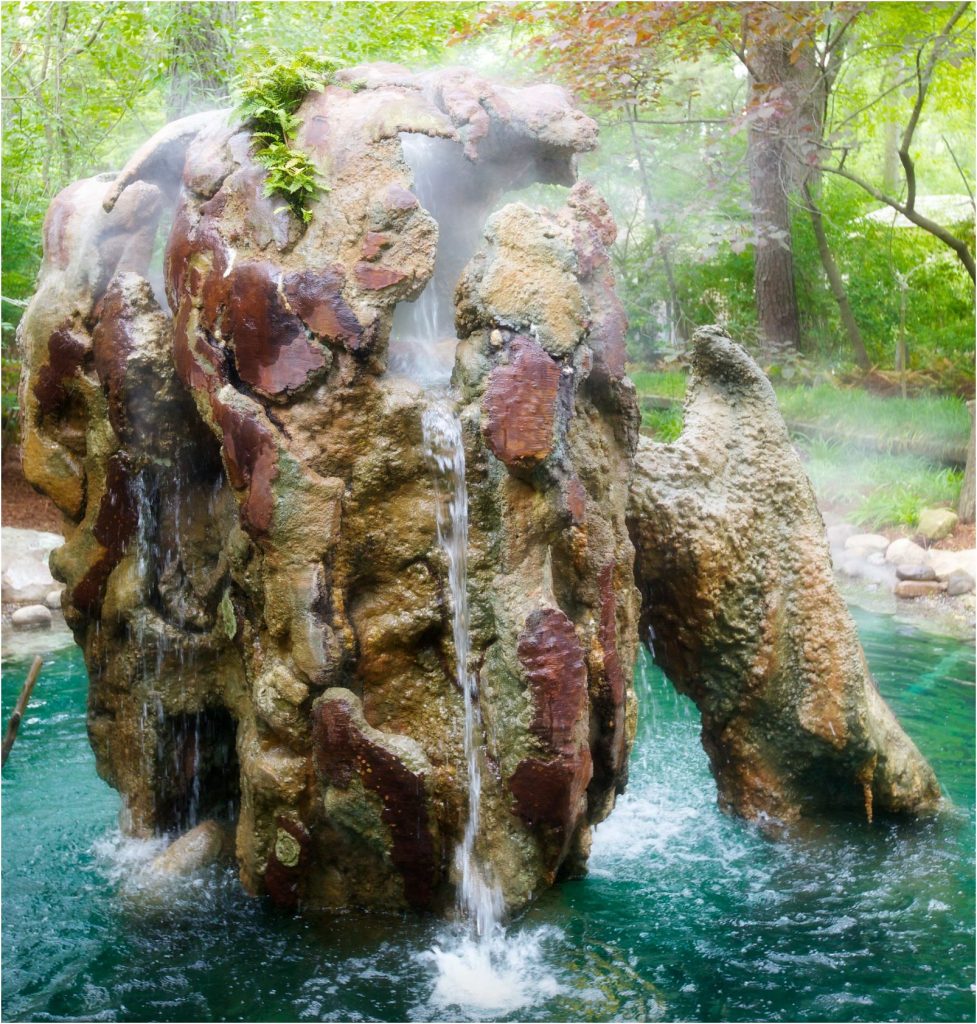

This first watershape was a perfect setting for that approach to design. It’s freeform with complex contours, about 80-feet long and 25-feet wide at the widest, down to roughly eight feet at the narrowest point. It works as a kind of hub for the property and as you follow the path around it, seeing different views with layers of plant material, stonework and art.

The idea was to ease the water into the landscape. Back in those days, we were using EPDM liners for the primary containment structure, rather than concrete. We built some sharp walls to define the boundaries of the water. But then we visually fused it into the landscape. It has a large shelf around the edges that we used to compose the edge treatments with plants and boulders.

We built an under-gravel biofilter system around the entire perimeter of the pool. Based on my background studying water gardens and how aquatic ecosystems work, I knew the system would support water clarity over the years, and it has.

It also involved this unusual sculptural element mounted in the center of the water’s surface, which is what separates this body of water from a typical pond. It’s very abstract and strange, and extremely difficult to describe. It looks like a place where the villain from a James Bond movie would live. It’s unlike most any rock formation you’ll see, with the exception of a very few places.

BEYOND THE WATER

In terms of project scope, there was a real mushroom effect when Hermanson recognized my ability to understand his ideas and to communicate those ideas to my staff. He could see his vision coming alive.

They were so impressed with our stone/masonry work and they asked us to stay on to work on all the stone and hardscape elements, so deeper into the process we went.

Hermanson wanted to make a garden that transcends time – a place with living trees and dead trees, where it appears the earth is collapsing upon itself and reclaiming the space. Stone walls are bending over, nothing was set in a straight line. In masonry work, we’re taught to think in terms of everything as being square and plumb. We threw all that out. Hermanson wanted the whole place to look like a giant picked the property up like a huge carpet and shook it.

At the same time, because the idea was for these things to last forever, everything needed to stand up structurally. It may look like it’s all in a state of advancing natural entropy, but from a technical and structural standpoint, it’s as solid and thought-out as a Frank Lloyd Wright cantilever, while at the same time taking organic design to a whole different place.

FLOWING STONES

Hermanson had already started doing his own stonework but was rightfully concerned about how it would hold up over time. My staff and I did have a great deal of experience in dry-stone masonry, so we came in and started either replacing or shoring up his work using different techniques, while still honoring the original design concepts.

One of the things he created was a massive 100-foot-long dragon, which was a gorgeous work of art and imagination, but it was beginning to show some signs of failure. Not only is the dragon massive in length, its head and neck rear up about 30 feet in the air. The sides, belly and legs are stone. The spine is actually plant material — a spikey type of holly – and, yes, the dragon does breathe fire.

This is where it really became fun. Hermanson made the dragon scales, thousands of them in all sorts of sizes, from stone material he harvested near his home. The stone would break apart into fragments that peeled off in layers – perfect for making dragon scales.

We started reworking the whole thing by removing the sides and belly of the dragon. We drilled small holes on the inside surface of the stones, and then installed an anchor system, similar in some respects to what you might use in rock climbing.

We mounted the bolts into the rock in such a way that the entire piece would have to break apart for it to fail.

We poured a massive concrete footing that takes up the entire belly of the dragon, end to end. Then we developed a network of aircraft cables mounted in a variety of brackets, fittings, nuts and bolts — many custom crafted — creating a massive, suspended rigging in the shape of the dragon. Finally, we suspended the scales on the framework of cables.

When the dragon’s scales were all hung in place, we locked them in with a layer of interior concrete so they would never move. We had to take large pieces of rock and essentially hang them out in space in such a way that it looks as if they should fall over, but never will.

It worked. Now it looks like the only way these stones could be where they are, and not fall over, is if they were actually part of a giant dragon. It’s a compelling visual effect. It took us just about year for that part of the work. And, the dragon does breathe fire.

CONSTRUCTING NARRATIVES

The dragon is only one of the many highly unusual features of The Uncommon Garden. In one of the waterfeatures, there’s a structure rising out of the middle that’s comprised of two almost identical stone “towers”. Hermanson had found a beautiful blown-glass globe, originally made as a bobber for fishing nets in Japan. He wanted it mounted at the top of a structure between two towering boulders.

Although not the specific intent, I couldn’t help thinking of the iconic Eye of Sauron from “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy.

The first step was to find the right stones. We were lucky to have a great stone-yard nearby where I found two “sister” stones that were perfect, almost like mirror images of each other. Interestingly, they didn’t come from the same quarry at all, or even from the same region; but they couldn’t have been more identical. They looked like someone had split them in half for this exact purpose — same height, same shape and same color and texture.

The question was how do we embed the glass globe between these twin monoliths and then move and install it, without breaking the glass? First, we made a mock-up globe out of Styrofoam and then started using that as a guide to create a spherical internal relief between the tops of the two pieces.

Hermanson wanted it to fit very tightly, like the stone had grown up around the globe. We created a very tight eight-inch space around the stone, which allowed us to neatly mount the globe between the stones.

The problem then became how do we get in place? I knew we would have to set in place during the steel phase of the waterfeature’s construction, which in this case, was made of shotcrete.

We built an extremely rigid steel cage, doweled the stone into place, and essentially created a safety armature that would protect and hold the boulders in place. The trickiest part was picking this thing up, moving it to the site and then lowering it into place, without breaking the globe.

When we mounted the structure in the armature, we used what is known as a “Lewis Pin” technique where you dowel into the stone material at an angle, using gravity and leverage to hold the stone in place. Then we shaved, shaped and colored the base of the pedestal supporting the boulder to look like an extension of the boulders.

In the end, we didn’t crack the glass, and the whole thing is sturdily in place years later – as though the Great Eye of Sauron endures, at least in Chapel Hill.

MYTHICAL WHIMSEY

Those types of thematic features are present throughout the garden. Inspired by our successes, Hermanson started thinking in even bigger terms. For example, he decided he wanted to place full-size dead trees.

So, we harvested a 30-foot cedar tree, which we installed with a crane; and, using a system of large knurled dowels drilled deep into the heart of it. The tree was mounted in a concrete footing, keeping the footing high enough that it wasn’t exposed to moisture in the ground.

We wound up with three cedar trees and two hollow walnut trees using the same technique. There’s also a massive metal “dead” tree, created by metal artist, Ray Toland, whose work is on full display throughout the garden.

While the use of plant material is thematic in that it supports the idea of natural entropy, there are a number of other elements that are more literal. The use of cultural iconography shows up in a number of places, including a number of large animal totems, symbols from various world religions, a troll, and a replica of a Moai from Easter Island, among many other notable works.

One of my favorite creations is the “Wave Room,” a truly unusual watershape that features a cantilevered concrete structure with a sheeting wave you walk under and behind. Again, we were challenged, this time to create a structure that appears to be suspended in space.

When we started, I was already working with poured-in-place concrete but not shotcrete, at least not in terms of using shotcrete to create vessels that contain water. The way we were working here, we were able to grow into shotcrete work over time, without much risk. Today, with my business partner we run an expansive dry-mix shotcrete company as part of our overall operation.

Getting me into concrete applications is just one of the many things I owe to this project. It gave me an opportunity to use my background in the arts and garden design in a way that few ever do, and ultimately I grew as a professional. I can’t think of very many situations that can do that for you.

That kind of opportunity to learn, grow and create is truly uncommon.

Ryan Oakes is a professional watershape designer and president of Clearwater Construction Group, Inc., Waterforge, Revolution Gunite and Revolution Pool Finishes, all award-winning firms in their respective trade.