The Shimmering Spires of Jade Mountain

St. Lucia’s Jade Mountain is one of the world’s most unusual and luxurious resorts, a renowned masterwork in the organic architecture tradition opened since 2006. One of its unique finishing touches involved creating sculptural glass-tile spires atop the building, an artistic task David Knox enthusiastically embraced in the spirit of the place, and the man who created this entirely unique resort.

By David Knox

Nick Troubetzkoy, architect, hotelier, and creator of Jade Mountain, passed away on November 25, 2024, in London. He was a creative visionary and a masterful purveyor of the good life, and one of the most enjoyable and fascinating people I’ve ever met.

His visionary spirit and fearless approach to architecture first took shape in a resort named Anse Chastanet on the island nation of St. Lucia in the southern Caribbean, a place that embodied his commitment to harmony with nature.

His work developing the resort, which he created from almost nothing, laid the groundwork for what would become his crowning achievement: Jade Mountain, located on a rugged hillside on the Anse Chastanet property, a resort within a resort. It’s a monumental architectural achievement that stands as a testament to his love for Saint Lucia and its people, and his commitment to turning luxury accommodations into an art form.

With Nick’s passing still fresh in my mind, the following is very much a tribute to his creative spirit and process. In this case, it was a sculptural glass-art installation on the structure of Jade Mountain that was in many ways a finishing and defining aesthetic element.

MADE OF JADE

The construction of Jade Mountain spanned over three years, employing more than 500 Saint Lucians during its creation. For Nick, one of the greatest rewards of the project was showcasing the incredible craftsmanship of the local workforce. Today, having worked on Jade Mountain is a badge of honor mark of excellence for local artisans and builders alike.

The resort’s legendary success speaks for itself. It has been celebrated in media worldwide, garnering rave reviews and the highest ratings. The unique design and almost unparalleled natural beauty of the setting conspire to create a vacation experience unlike any other, and it all emerged from Nick’s creative vision and dogged determination to make it real.

He had been an avid collector of antique carved jade mountains for over 35 years. His collection, which he had already begun before arriving in Saint Lucia, eerily mirrored the island’s breathtaking landscapes, including its most famous landmark, the Pitons, two dramatic peaks that rise above the island, presiding like ancient jungle-covered masters of the landscape. His deep affinity for these ancient carved stones may have, in part, inspired his lifelong devotion to the island and its people.

A big part of Jade Mountain’s unusual beauty is its use of native materials. For example, the living areas of the rooms, aka. sanctuaries, are finished with more than 20 different species of tropical hardwood flooring and trims, all harvested in an environmentally correct way on St. Lucia, neighboring islands and the country of Guyana. A multitude of hardwoods were used including Purpleheart, Greenheart, Locust, Kabukali, Snakewood, Bloodwood, Etikburabali, Futukbali, Taurino, Mora and Cabbage Wood.

The interior walls are finished in a crushed blush toned coral plaster quarried in Barbados. The exterior is in massive rough concrete and imbued with locally quarried stone, with all the window openings framed with 3-by-18-inch tropical wood mullions and muntins, in-filled with movable jalousie louvres. The flooring exposed to the weather is finished in quarried coral tile from neighboring islands.

WAVES OF EXPERIENCE

I first became involved in Jade Mountain as the creator and supplier of the glass tile used in the sanctuaries and their famously luxurious private vanishing edge swimming pools. In essence, my role was to interject and create color via glass tile as an important design element. And, as described below, I would make glass panels that now adorn the structures numerous concrete and steel spires.

To experience Jade Mountain is like stepping into another world. There’s a palpable energy that emerges from the interplay of elements; the light, the air, the architecture, and the seamless connection to the ocean and mountains. You don’t just stay at Jade Mountain, you become a part of it, and it, in turn, becomes a part of you. At least that’s the way I’ve always felt about spending time there.

Nick once described Jade Mountain’s design as improvisational jazz, working with the same set of notes but arranging them differently each time, in response to the natural environment. He believed this approach would not only shape the architecture but influence the guest experience.

“What I really want to do with Jade Mountain is re-evaluate and redesign the basic concept of a holiday/hotel experience,” he once told me. “I want to create individualized spatial environments that enable guests to forget about the furniture or the fact that they’re in a hotel room – in essence, to forget about everything but experiencing the psychology of the space on an intuitive level.”

There is no question he succeeded. I remember sitting by one of the pools, watching the light shift across the unique glass tile I had created, and realizing that this was art in motion. Nowhere else had I seen such a harmonious interplay between a built environment and nature.

Nick’s vision extended beyond simply constructing a luxury resort, he wanted Jade Mountain to be reclaimed by the jungle, for nature to gradually blend with the structure over time. Unlike most architects who strive for pristine, polished perfection, he embraced organic entropy, much like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

TRANSLUSCENT VISION

As Jade Mountain neared completion, Nick approached me with a challenge: to create glass-tile artwork for the concrete spires that support the structure. In true Nick fashion, he didn’t dictate what to do but instead simply pushed me to explore.

One morning, he called me. “I’ve got something important to send you,” he said. I was expecting detailed architectural plans, instead I received a diagram that looked more like a crossword puzzle with three words saying, “Less is more.”

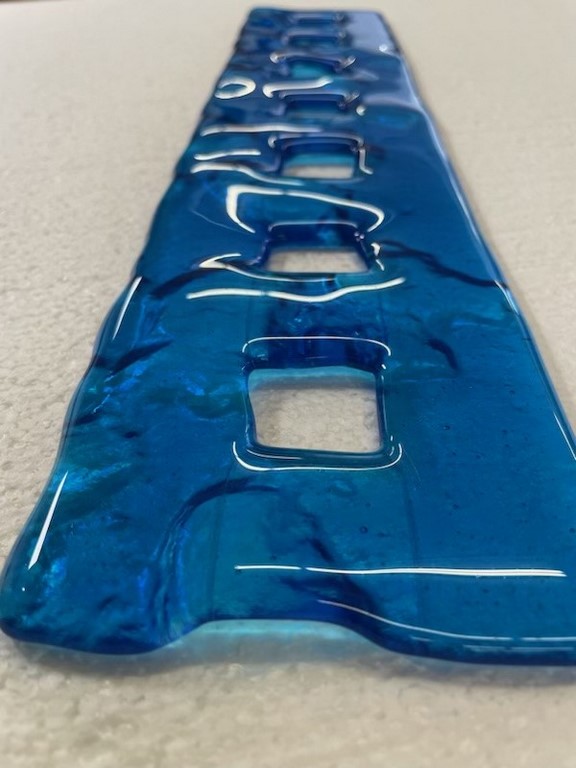

It was just the prompt I needed. At that moment, I realized Nick wasn’t giving me instructions, but offering me a way forward. I had been lost in the details, and his simple guidance pulled me out. That was the moment I conceived the ladder concept, an intricate mosaic of 285,600 pieces in total, all hand cut (by my son Brian) on a special jig we made.

Nick saw the unfinished rebar at the top of the spires as an homage to the unfinished dreams of the Caribbean. He wanted to transform that raw imperfection into beauty, making each spire a work of original art. (Jade is known in China as the “stone of heaven”. At Jade Mountain, our columns reaching out to heaven became an important part of the design.)

I traveled to Saint Lucia with my daughter in 2008, experimenting with how the glass elements would be incorporated. What began as an abstract vision turned into something unexpectedly organic as the spires became bird’s nests, literally. Birds began nesting inside them, perching on the colorful glass as light passed through the tiles. It took almost no time at all before nature had claimed the artwork as its own.

Glass tile presents a unique challenge. It’s transparent, but not in the way a stained-glass window is. I had to consider reflections, refractions, and viewing angles to maximize the interaction of light and color.

I began to see the project as a rare opportunity, to push the limits of color and texture, using shades and materials that would be impossible to mass-produce. I worked with at least 42 different colors, incorporating wild oranges, deep blues, shimmering greens, and a kaleidoscope of hues that shift throughout the day.

And as always, Nick embraced imperfection. He told me: “If you can see a pattern, it’s wrong.” He wanted the final product to feel as if it had emerged organically, just like the rest of Jade Mountain.

MAKING GLASS ART

At the heart of the manufacturing process was a methodical layering technique, akin to double-welding, ensuring that each bridge point in the glass structure was reinforced. Cross-hatching the layers provided additional strength, creating a system that could withstand both environmental stressors, and the test of time.

The importance of annealing, the controlled cooling process that prevents internal stress, was paramount, as was maintaining the purity of the glass’s structural compatibility. This level of control and testing underscored the commitment to both safety and durability, essential in a material so susceptible to thermal expansion and shock.

Despite the precision behind the glasswork, the installation process itself evolved organically. With no predefined specifications, the project became an exercise in problem-solving, almost like assembling a massive puzzle. The comparison to Lincoln Logs (a childhood construction toy) is fitting, as each piece had to interlock securely while allowing for necessary movement.

The use of stainless-steel wiring, carefully chosen and tied to prevent over-tightening against the rebar, provided a solution that accounted for expansion and contraction due to temperature fluctuations. Testing for thermal shock, a crucial step given the sometimes-extreme shifts in temperature, further ensured that the glass would remain intact through blazing hot afternoons and sudden tropical downpours.

The scale of craftsmanship involved in this project is staggering. The sheer volume of labor— the miles of glass cutting, thousands of square feet of material—evokes the image of artisans in Italy creating elaborate mosaics, where patience, skill, and endurance are essential.

The installation process became an improvisational dance, with Rastafarian artisans assembling the glass pieces on scaffolding, responding to the ever-changing light and landscape. Once installed, the compositions of glass, color and light came alive like natural beacons, shimmering in the ever-shifting light. Like the place itself, the spires are works of environmental art that can only be truly appreciated by being there.

The fact that the installation has remained in pristine condition for years, prompting additional orders, speaks to the triumph of its design.

UNIQUE LUXURY

Jade Mountain is not for everyone. Those expecting a traditional five-star resort experience may be surprised by its open-air design, its raw natural beauty, and its deliberate rejection of conventional luxury. Some guests even struggled with the lack of enclosed bathrooms, something Nick found fascinating.

For those who embrace it, however, a visit can be transformational. It’s an experience rooted not in opulence, but in connection to the earth, to the sky, and to oneself. It is a place made for lovers, seekers, and those who appreciate the beauty of interconnection with nature and tranquility.

Nick saw it as a modern-day Roman temple, a place where guests could be transported beyond their daily existence. Some people compared it to a cave dwelling, a place to stand at the edge of the world, looking out over the horizon, waiting for something extraordinary to happen.

But Jade Mountain doesn’t ask you to wait.

It opens you up to color, to light, to space, and to an expansion of the senses. The experience removes the filters we rely on to navigate the world, allowing the full spectrum of sight, sound, and sensation to flood in like a tidal wave. That is why, to this day, I remain proud of the work we did at Jade Mountain. From the pools to the sanctuaries to the spires, every element was an act of artistic discovery.

We didn’t just create a resort. We created a place that has never existed before, and in all likelihood will never exist again.

David Knox is the inventor of Lightstreams Glass Tile and tile sales manager for Pebble Technology International/Lightstreams Tile Division.

All photos courtesy of Jade Mountain.