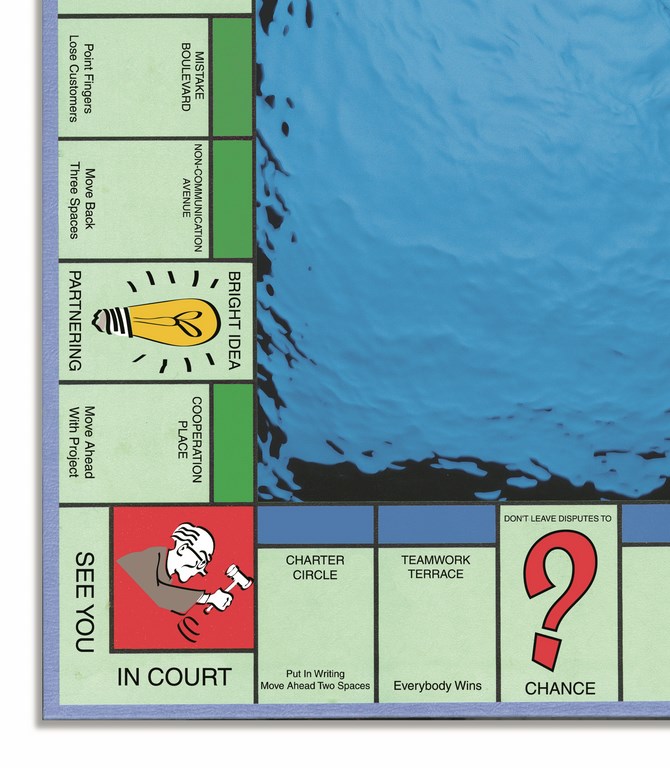

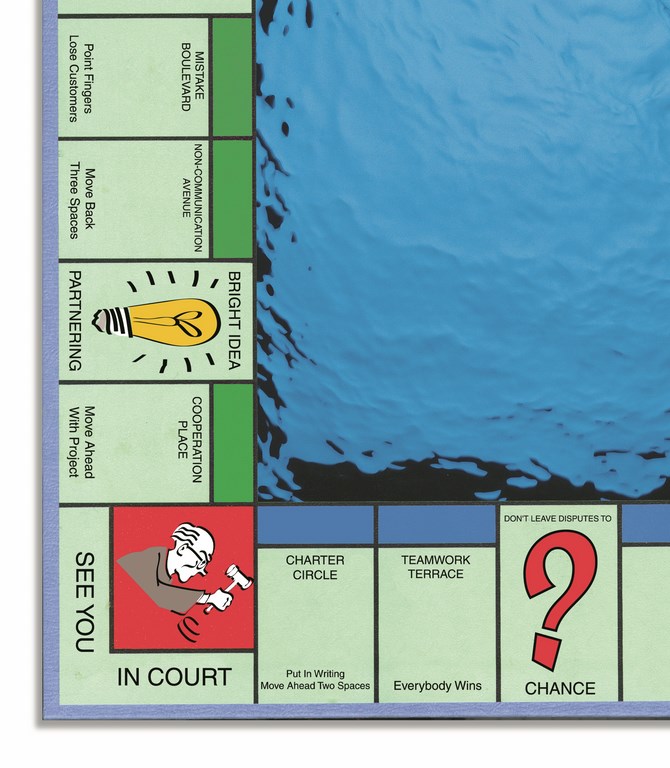

The Power in Partnering

Construction can be a tough business: Even minor conflicts or disputes often lead to courtroom battles, and you can hardly blame people in the trades for thinking ‘potential lawsuit’ every time they sign a contract. One way to avoid these lose/lose scenarios, says aquatic consultant Curt Straub, is to implement a simple, up-front agreement designed to foster cooperation among designers, engineers, contractors and clients.

When you work with someone in a cooperative effort to achieve a common goal, the odds are greatly reduced that you will wind up one day facing that person in a courtroom.

The neat thing about this form of cooperation, also known in business circles as partnering, is that it can do much more than keep you off your lawyer’s time clock. In fact, partnering is something that all of us in the industry can use to our advantage – and to the advantage of our customers.

Better yet, partnering is a simple, practical concept that can be implemented with relative ease, even by people new to the idea. It’s already being used in large commercial projects, where the needs and activities of many trades and interests must be coordinated, scheduled and accommodated – and there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be applied in all cases where multiple disciplines have roles in a project, be it residential or commercial.

DEFINING PARAMETERS

What does it take to launch a partnering program? For starters, it requires a distinct mindset – and a commitment based on that mindset – of everyone involved in the project. No exceptions!

To be effective, the partnership depends on an atmosphere of mutual respect, understanding and teamwork. All parties to the agreement must assume responsibility for their performance and participation, and cooperation and communication must occur at all levels. Finally, all parties must accept the fact that problems will arise and that solving them (rather than defending one’s turf) is the common desire of all partners.

Partnering is, in fact, both simple and idealistic – but it is also very much down to earth by virtue of its main objective: successful completion of the project.

To be sure, that goal should apply to everything we do in business. In the real world, however, we are all susceptible to error – and as more people get involved, the opportunities for those errors as well as conflicts, disputes and lawsuits all tend to multiply. This is where the rubber meets the road with partnering: that is, in the resolution of occasional mistakes and misunderstandings.

Consider the status quo: Historically, if a mistake is made on a job, the attitude of anyone affected by the problem is that someone, somewhere, somehow, is going to pay. We might call this the “I’ll see you in court” reflex. This reflex gets good workouts poolside, for example, in arguments over why the finish failed or how the tile didn’t match the sample or why the extra main drain wasn’t in the original plans and specs. These debates can get ugly in a hurry – definitely bad for business and very poor professional form.

Many of us with some years behind us in the watershaping trades have been subjected to this adversary tradition for far too long. In fact, it almost seems like a requirement, a necessary part of doing business. So let me ask a key question: Why do mistakes on a job so often mean a visit to a judge?

It all boils down to a fundamental lack of communication, to a lack of a sense of shared responsibility. Let’s face it: Mistakes are going to happen, and on almost every job that goes in. Knowing that, it becomes incumbent upon us to handle those mistakes in a way that fosters success rather than litigation.

That’s what partnering is all about.

PARTNERING PARTS

My dictionary defines a partner as “one of two or more persons engaged in the same business enterprise and sharing its profits and risks.” In this sense, watershape designers, engineers, general contractors and subcontractors are already “partners,” whether they recognize it or not. The difference comes in making effective use of those ties – or in squandering the opportunity to work as a team.

That said, there are four major components of effective partnering:

• a total commitment to success at all levels

• upper-level management support

• open communication and trust

• having the right people in place to implement the partnering method.

Acceptance of responsibility as a group is also a factor: If one partner makes a mistake, the entire group is responsible for solving it, not just the individual partner. In that sense, partnering takes the principles of responsibility you probably apply within your own business and applies them to a group activity.

So who’s in this “group”? The short answer is that it includes everyone involved at all levels. Expanding a bit, the list of those involved should include:

• owners

• aquatic directors/pool operators/service technicians

• consultants

• designers/architects/engineers

• project facilitators

• general contractors/subcontractors

• materials and equipment suppliers

• financiers

• insurers

• mediators/arbitrators/lawyers.

That’s a diverse group of interests, and getting them all into alignment takes effort. Yes, it’s easy to say, “Let’s all just get along,” but without something formal, it’s also easy to fall back into the same old patterns of blame and defend. To be effective, in other words, partnering has some real requirements and is not always easy to arrange.

MAKING IT WORK

Let’s get down to cases here and define the sorts of interactions at work in partnering agreements. (Note: These projections apply primarily to commercial and institutional rather than residential projects in terms of scope and scale, but the same principles of cooperation and communication apply to all watershaping projects.)

[ ] The owner and aquatics director work together to determine the use of a given facility and associated requirements. [ ] The aquatics director in turn receives input from the manager, pool operator and service technician. [ ] The consultant handling the project reviews these expectations and requirements with the owner and aquatics director, assisting in development of the project. [ ] The owner, aquatics director and consultant work together to select a design/engineering team, a project facilitator and the financier. [ ] The design team prepares the project documents, receiving input from the owner, aquatics director and consultant throughout the process – and, in turn, works with the entire team through the bidding process and ultimately in selecting a general contractor.This ladder of interactions informs the attitudes and disposition of the team from top to bottom, side to side and beginning to end. In other words, everyone is empowered to play their parts, knowing that they have been selected deliberately, with full support of the parties at the various other levels of the project.

This summary obviously simplifies what can be a complex set of relationships and processes – and certainly does not define everything involved in the construction of a commercial pool. Nor does a structured “teaming” of these professionals eliminate the inherent problems that develop with construction. In other words, partnering does not preclude the need for a written contract.

What it does do, however, is clarify expectations for performance and areas of responsibility, thus eliminating a great many potential problems along the way and, more important perhaps, providing a mechanism for solving problems in which everyone involved assumes some level of shared responsibility.

What I’ve found in projects that have been installed using this sort of partnering model is that problems are usually handled quickly and at the lowest level possible, most often by workers in the field. Some projects formalize things by prescribing a problem-solving time frame (usually 48 hours). It’s remarkable how often that target is met, even with seemingly severe problems.

Finally, it’s important to note that while partnering probably works best if implemented long before construction begins, it can still work even if it is applied long after the project is under way.

PARTNERSHIP IN PRACTICE

Typically, partnering begins with an orientation session or conference conducted with representatives of all parties on hand. As important as defining the partnering process, the meeting must include instruction in the art of improving communications within the team.

For larger projects (such as those run by the government), this initial gathering is conducted by a facilitator who assists the team in developing the terms (or charter) that all participants agree to sign. This agreement elaborates on the project’s scope, outlining shared goals and the methods necessary for success. (See the sample partnering agreement below.)

Beyond this initial meeting and the signing of the partnering agreement, the process should also include a team-evaluation component to track progress and/or shortcomings in the overall project. These follow-up meetings are conducted for the specific purpose of identifying areas that need improvement and for devising plans for implementing corrections in the most expedient way possible.

This problem-solving function is where the critical work of partnering really takes place. When conflicts arise (as they do almost inevitably in any project, let alone a large commercial one), it can be tough to overcome the tendency to fall back into adversary postures.

One pre-emptive approach is “alternative dispute resolution,” or ADR. With this mechanism, the owner and contractor each designate individuals within the affected organizations to work out any problems. This group includes people from the field through to upper management, matching individuals of similar station from both sides.

In this sense, partnering does not assume trickle-down power and control. Rather, it embodies an effort of equals to accomplish the task of resolving problems. This sense of equal footing fosters a shared level of respect. It also works to place the focus on the problems at hand, enabling those involved to isolate the issues and come up with a solution that is free of pecking-order constraints and pressures.

MAINTENANCE SCHEDULE

When a dispute does arise, an immediate attempt is made to resolve it. This initial effort should involve mainly those at the lowest level possible. If they are unable to come up with a plan, the issue moves on to the next level, where the two parties have a similarly restricted time frame to reach a resolution. The process continues up the ladder until the process is resolved.

The aforementioned progress and evaluation meetings afford all parties a wonderful opportunity to stave off conflicts that may result from potential or pending problems. In fact, proponents of partnering often comment on the effectiveness of dealing with a problem ahead of time, well before unnecessary costs are incurred or emotions have a chance to flare. As these pitfalls are avoided, the goals and principles of partnering are refined and reinforced.

In other words, the process of partnering and the reinforcement of teamwork become the overriding focus – a one-two combination with the capacity to knock down just about any individual problem.

The traditional adversary relationships are explicitly rejected here. Under the partnering agreement, there is a clear recognition that all parties are working toward the same goals and acting in the interest of shared success. The importance of moving effectively through a project’s phases thus replaces the fear and animosity that can arise almost naturally out of the contracting process. Under partnering, cost overruns and change orders are minimized as well.

Clearly, owners and contractors need to recognize that partnering cannot eliminate all disputes on the job site. Even in the best relationships, differences of opinion can arise. But these disputes need not destroy the partnering relationship if the partners approach their responsibilities with trust and a spirit of cooperation.

In other words, partnering is not a panacea for all problems and cannot be used to bail out a partner with, say, serious financial or management problems. When ability and integrity are coupled with a commitment from the partners, however, partnering becomes a tremendously positive force that stands to revolutionize watershaping at all levels. After all, it makes good business sense!

Curt Straub has been active in the pool industry since 1962, when he joined his family’s construction company as a laborer working on backyard installations in the greater Kansas City, Kan., area. In 1970, Straub moved into the front office and headed up the company’s design and sales teams, a position he held until 1990, when he founded Aquatic Consultants. A specialist in pool and spa design, he offers mediation and conflict-resolution services along with his emphasis on structural evaluation. Straub is a long-time member of the American Concrete Institute’s Kansas Chapter and is past chairman of ACI’s swimming pool committee. He is also a past board member of the Master Pools Guild