The Life of Streams

Streams are about movement, journeys and experience. They create connections within the landscape and they even tell stories. As Anthony Archer Wills explains, designing and building streams is a form of watershaping that is best realized when based on keen understandings of nature, narrative and motion.

By Anthony Archer Wills

Sometimes rushing and turbulent, sometimes placid and meandering, at times scarcely audible, at others gurgling in deep hollows, rivers and streams can be apposite metaphors for life itself. Relentlessly propelled downhill by gravity to empty themselves at their destinations, in a lake or the ocean, they all have their own course and tell their own stories.

We may speak of our own journey from birth to death with all its twists and turns, successes and failures, as the “River of Life”. Some may try to go against the flow, while others are content to allow life to simply follow its course and let the current take them as it will.

In a more literal context, we know that rivers and streams can be immensely powerful, sculpting the land itself, carving channels and gorges, creating ridges, and carrying rocks and sediment to create new lands; and, often transforming the human experience along the way. Watershapers who build water courses, from significant streams to the most delicate of runnels, are in effect harnessing the power and, indeed, the meaning of rivers and streams.

As designers creating the spectacle of flowing water, we are tapping into its power and fascination and bending it to our own purposes on behalf of our clients.

NATURAL FLOW

The character of a stream or river always depends on the local geology and topography through which it flows. In gentle rolling grassland, water may run over a bed of gravel in the form of a tranquil stream, often flanked by lush vegetation. Mounds of underwater plants wave gently in the current, whilst drifts of moisture loving, and aquatic plants attract butterflies, dragonflies and birds.

By contrast, the deep shade and heavy leaf fall in a woodland or forest entirely changes the character of a stream. The banks are brown with leaf mold following the spring flush of forest ephemerals, as the vibrant green of moss carpets the steeper banks and clings to the rocks. Splashes of bright green emerge where ferns put forth their fronds, highlighting the shade.

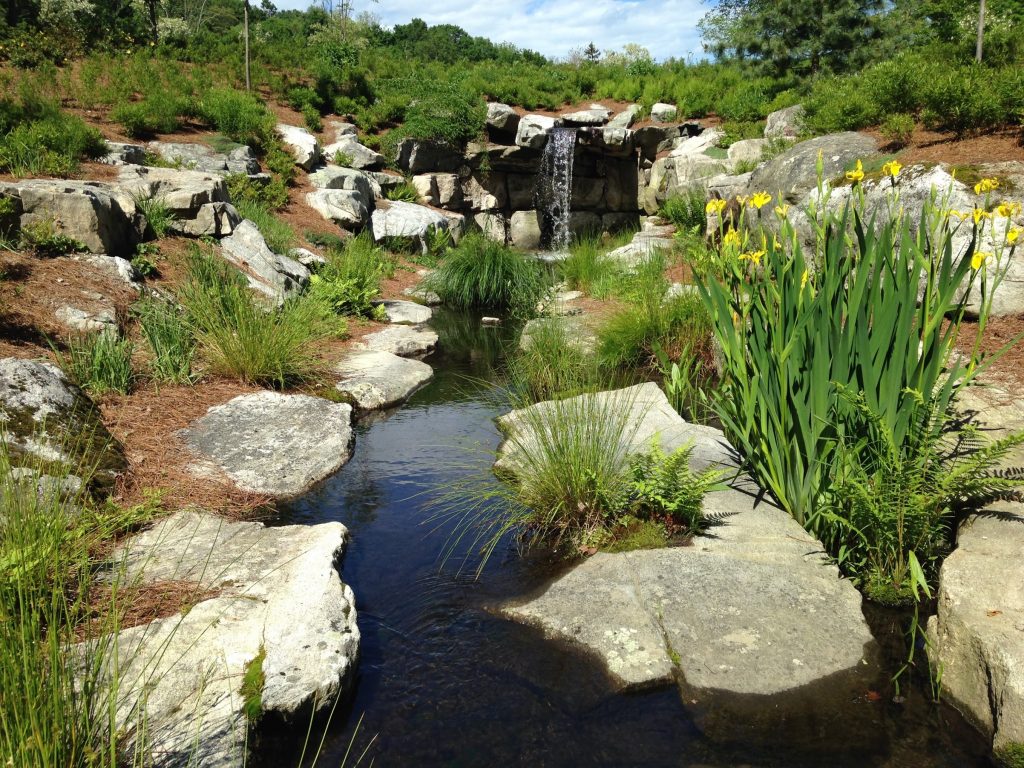

Different still, streams in rocky areas leap and tumble, boiling snowy white, sculpting whirlpools and gullies into rock, sometimes forming a series of rock-lined pools linked by waterfalls. Plant life is sparser on rocky streams where the beauty lies in the mossy, lichen-cover rock formations.

The moving water carves stone in truly remarkable yet logical ways, slowly and inexorably as the water patiently consumes the hard rock through which it flows. This is one of Nature’s lessons – the soft and yielding gradually overcomes the hard and inflexible. Streams cut downwards, making their own valley and channels. The water arms itself with stones and boulders which it carries helping the rock carving process. The water winds down mountain and hillsides, nudged to and fro by the harder rock outcropping, but always transforming the landforms over which it travels.

Indeed, studying different stream types in nature will provide insights into the design a man-made course might have in a particular setting. Considering first the water’s source, the watershaper must decide whether the source should emerge naturalistically, be it bosky or stony, perhaps from a small bog garden or seeping subtlety from a crack in mossy rocks. Conversely, the site might be better suited for it to appear constructed by human hands, emerging from a stone or brick culvert, or contrived with pebbles and a millstone, perhaps from a wall mask, or stone trough.

The wonderful thing about naturalistic streams is they can gracefully harmonize with any style or period of architecture because it will be perceived as though it existed long before the people came along and altered the landscape with buildings, roads, walls, bridges gardens and hardscape. As with ponds and lakes, it will seem as though the water was there first with the house site chosen to enjoy its proximity.

Nature owes nothing to any sort of stylistic modality and will appear at home in all places. In nature, water is often a common factor linking many diverse features within the landscape, particularly in complex systems with subsidiary channels or pools. Similarly, water can be used to provide a link between the different styles within a garden, because it is the one element that appears to belong everywhere.

For example, water flowing close to a house then moving out into the garden will forge a strong visual connection between the two entirely different localities. Consider a country house with an authentic water source close by, perhaps disguised by an arched springhead or a wall mask; the water might proceed in a formal canal, passing between flagstones, topiary trees and knot gardens, but then flow out into a wild landscape beyond. The eye is drawn in both directions, back toward the house and outwards into the wild.

It is in this journey that you can mine stylistic purpose. In the more architectural confines near the house, you keep the edging constant, using materials that might be in harmony with, or drawn directly from the house; but, then when you move into the more natural-looking landscape, the edges transform as it moves through wild turf, over outcroppings of rock, waterfalls, or through scented swathes of shrubs and undulating meadow.

BENEATH THE SKIN

Before painting a nude, an artist must understand bone structure, sinew and muscle. Similarly, in order to create an accurate reproduction of a natural stream, it is essential to develop a good understanding of its underlying geology.

From the source, which might be the tiniest trickle or a mire of peat and grass, the stream begins to take shape as a definite water course. At this stage, the geological narratives emerge and become apparent, as the formation breaks free of accumulating silt and plant material in the form of beautiful mossy rocks, around which the water sinuously winds.

This interplay between the contemporaneous water, and the relative permanence of the earth it sculpts, reveals itself throughout the stream course. In some places it will spurt energetically, forced between large boulders, while in other locations the water will split to pass on either side. A cluster of smaller boulders might create a waterfall or rapid, passing over pebbles and boulders, its broken water sparkling brightly and filling the air with its babbling music.

In other places still, eddies form behind larger stones, where drifts of sand and gravel are deposited as the stream makes its way down the hillside. Here you might be taking your design cues from the local geology where rounded rocks indicate ancient water flows that smooth the rocks and deposit them as alluvium.

In some streams, the underlying bedrock forms the dominant feature. Where water flows across it, you can create a wonderful field of visual complexity and movement, as if the water is scrimmaging with earth below. Broken pieces of rock lodged at precarious angles create a range of water patterns, from fans and converging shuts to whirlpools, plumes and aerial fans. Infinite complexity is forged by the water being in constant conflict with rock. In construction I use large, preferably mossy or lichen encrusted rocks to ensure bank retainment and try to be as faithful as possible to the local geology.

This is all very different from meadow streams, which are also defined by geology, but a very different affect. These gentle streams are not jagged and rocky, but have soft banks with vegetation running right down to the water. Whenever I create one of these streams, I follow nature as closely as possible, taking soil right down to the water along the margins, covering any hard edging or liner that might be visible, and always allowing the stream course to softly oscillate as it meanders through the space. Here, stones and small boulders can be placed at the turns to thrust the water in the desired direction and prevent erosion.

In the wild, the sides of streams may not always manage to contain the flow: blockages or sudden spates may cause the stream to overflow for a while. I’ve found it helps to bear this in mind when placing rocks.

It always helps towards the goal of naturalism by building in the factor of time in one’s compositions. I set the ledges back into the land, as though the water had exposed them for a time and then receded.. Where you have boulders, allow some of them to protrude from the drier ground a little way back from the stream’s edge, thus disrupting the unnatural “string of pearls” look with the suggestion of an ongoing epochal narrative of struggle, advancement and retreat.

CONNECTIVE TISSUE

Both in nature and in our built environments, streams forge connections. In nature, a stream will encounter rapids and waterfalls as it descends a slope. These are what I call the “predictables”. This same course will likely contain rock pools, which themselves can be varied and highly individualized.

Some may be like cauldrons, scoured by trapped stones whirled incessantly around by the current. Others might be unexpectedly large, allowing water to idle and spread, playing host to a variety of plants and fish.

The stream may encounter an area of uncertainty in which it opens out into a bog where there is no apparent water channel. Here the water will seep through the thick vegetation or sphagnum moss, and then gather itself to continue the downward journey.

Natural patterns can supply us with a great deal of inspiration. Pools can vary in size, shape and depth. Streams will branch into spidery fingers and rivulets, running at different levels, parting for large rock formations, or seeping into areas of bog plantings. You could use this method to create a small island, which can be reached by small steppingstones or even a bridge.

There are infinite ways you can infuse the space with interest and variety, and yet have it all seem comfortable and at home. A small grotto, brick culvert, or emerging underground channel, can be deployed to create unusual and attractive features that contribute to the story the landscape and its stream are waiting to reveal.

One should also remember the purifying benefits of a stream. It acts as a vast, elongated biofilter. Running through stones and gravel each piece will be coated in a rich biofilm of microscopic creatures all working on extracting nutrients and impurities from the waterflow. The plants form a natural wetland filter removing nitrates, phosphates and other impurities, allowing the water to become pure and clear as gin.

MYSTERY OF THE JOURNEY

Tennyson in his Lady of Shalott describes the river running down to Camelot as “the road that runs forever.” A river might encounter many surprises on its journey, and what lies beyond the next bend is a mystery.

In building streams, we can create this constant sense of anticipation, a skill at which the designers of Japanese gardens were particularly adept. They used the physical and visual movement of water, plant and rock forms to excite curiosity, prompting visitors to explore further.

A well-designed water course will exploit this curiosity and provide surprises for both the outward and return journey. A stream could lead you on a path around the garden and through many moods, styles and individual delights. Perhaps we are led through a bright, sunny and open expanse, and then into a dappled shade among a stand of birch, elm or maple trees.

The stream may unexpectedly widen out into a sunlight pool where fish bask beneath lily pads; or, the stream may disappear behind a group of scented shrubs, only to reveal around the bend an expanse of water iris. In another place — as the eye is drawn along a shimmering strip of water — a piece of sculpture becomes a focal point. If you choose to follow a path along the water’s edge to enjoy a closer look at the artwork, then you are unexpectedly rewarded with yet another expansive or intimate view or vignette.

In both the literal and figurative sense, streams are the embodiment of movement and journey. They are constantly responding to the setting and at the same time changing it forever. As we observe a stream, and linger by its edge, we join that process, if only for a time, along a path that is both eternal and ever-changing.

Anthony Archer Wills is a landscape artist, master water gardener and author living near Austerlitz, N.Y. Growing up close to a lake on his parents’ farm in southern England, he was raised with a deep appreciation for water and nature – a respect he developed further at Summerfield’s boarding school, a campus abundant in springs, streams and ponds. He began his own aquatic nursery and pond-construction business in the early 1960s; work that resulted in the development of new approaches to the construction of ponds and streams using concrete and flexible liners. Archer-Wills tackles projects worldwide and has taught regularly at Chelsea Physic Garden, Inchbald School of Design, Plumpton College and Kew Gardens. He has also lectured at the New York Botanical Garden and at the universities of Miami, Cambridge, York and Durham as well as for the Association of Professional Landscape Designers, from which he received the 2013 Award of Distinction. He is also a 2008 recipient of The Joseph McCloskey Prize for Outstanding Achievement in the Art & Craft of Watershaping.