ceramic tile

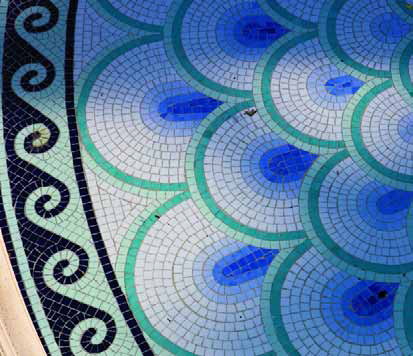

Artistry In Mosaics (Fort Pierce, FL) has published Mosaic Tile Master Catalog No. 28 in…

It’s often hard to tell exactly when you begin a career as an artist. As children, both of us loved to play with clay – but that’s been true of countless other children the world over for untold generations. And it really was just fun for us, but now when we look back on those days, we also see that, even then, we’d started on the road to our current calling. It helped, of course, that we were raised in a family of artists. Both of our parents drew and painted, and our father, James Doolin, was respected in the art world. But it was our mother, Leslie Doolin, who started it all for us professionally when she decided to paint on tile: Eventually we joined her in what was to become

It all started in 2002, when I was contacted by an architect who’d been retained to design a recreational complex for a huge estate in a wealthy Chicago suburb. I knew at the time that this would be big, but in those early days I had no clear idea exactly what it would ultimately entail. It’s a familiar story: Before the call came in, the homeowner had spoken with a number of pool-contracting firms in the area and had visited a number of projects that failed to impress her. The unusual thing is, at the time she called I was focused exclusively on pursuing large-scale commercial projects and waterparks and didn’t see anything even approaching a

Not long ago, I was asked by a reporter from The New York Times to define the main difference between swimming pools now compared to what they were 20 years ago. As we talked, it became clear that she was mostly thinking about technological breakthroughs in pumps and chemical treatments and the like. I confirmed for her that, yes, those products had come a long way. But I wouldn't let her stop there, suggesting that there was much more than a run of technical advancements behind the explosion of interest in watershapes in the recent decades. What we've also been seeing, I said, is a latter-day Renaissance of interest in classical notions of

Not long ago, I was asked by a reporter from The New York Times to define the main difference between swimming pools now compared to what they were 20 years ago. As we talked, it became clear that she was mostly thinking about technological breakthroughs in pumps and chemical treatments and the like. I confirmed for her that, yes, those products had come a long way. But I wouldn't let her stop there, suggesting that there was much more than a run of technical advancements behind the explosion of interest in watershapes in the recent decades. What we've also been seeing, I said, is a latter-day Renaissance of interest in classical notions of

When I was a kid, the conventional part of my education in environmental design came in helping my father, Jay Stang, plant parkways and blocks of Pinus Pinea across the city. The unconventional part - the part that apparently took firmer root as I grew up - had me admiring the plate he'd made from hardwood with the dozen split avocado pits he'd carved and mounted on the surface; it also had me listening to my mother, Judy Campbell, tell me that the earth was here first, that the garden already exists and that pathways, watershapes and structures are best built around what we find there. Those unconventional lessons - one about creativity and vision, the other about respect for nature and a method for approaching it - have stayed with me through the years and have given me access to a number of incredible projects. As is the case with most intriguing and fascinating designs, the one seen here flowed from a client with whom I developed a close creative connection that resulted in a free exchange of ideas¬ - a synchronized spontaneity that became a pattern for the entire design process. She always had strong thoughts about what she wanted, but she allowed me to interpret and express her ideas based on our conversations and the nature of the site. As designers, it's not unusual for us to be called on to use our skills and figure out what a client such as this one really wants and then suggest ideas we think will work. I call this process "environmental psychiatry" because, while so many clients have a sense of what they want and a laundry list of general ideas, few have a

When I was a kid, the conventional part of my education in environmental design came in helping my father, Jay Stang, plant parkways and blocks of Pinus Pinea across the city. The unconventional part - the part that apparently took firmer root as I grew up - had me admiring the plate he'd made from hardwood with the dozen split avocado pits he'd carved and mounted on the surface; it also had me listening to my mother, Judy Campbell, tell me that the earth was here first, that the garden already exists and that pathways, watershapes and structures are best built around what we find there. Those unconventional lessons - one about creativity and vision, the other about respect for nature and a method for approaching it - have stayed with me through the years and have given me access to a number of incredible projects. As is the case with most intriguing and fascinating designs, the one seen here flowed from a client with whom I developed a close creative connection that resulted in a free exchange of ideas¬ - a synchronized spontaneity that became a pattern for the entire design process. She always had strong thoughts about what she wanted, but she allowed me to interpret and express her ideas based on our conversations and the nature of the site. As designers, it's not unusual for us to be called on to use our skills and figure out what a client such as this one really wants and then suggest ideas we think will work. I call this process "environmental psychiatry" because, while so many clients have a sense of what they want and a laundry list of general ideas, few have a

We've always based our work as tile artists on refusing to allow existing rules and conventions to get in the way: We push at all boundaries and always seek something more exciting to create. That undaunted spirit of breaking new ground started with my parents, who established Craig Bragdy Design Ltd. in Wales just after World War II. Jean and Rhys "Taffy" Powell met in art school, had four rowdy boys and started the business by producing decorative ceramic products - coffee and tea cups, dishes, salt and pepper sets and a host of other smallish daily items. Even then, they were swimming against the tide: In the postwar United Kingdom, most people were interested in purely practical products and certainly

Most people I know have a favorite vacation spot, a favorite leisure-time activity and a favorite form of self-indulgence. In creating backyard environments for these folks, we as watershapers and landscape designers often find ourselves able to roll elements of one, two or all three of those "favorite things" up in a single package in ways that closely reflect our clients' passions and personalities. At my company, we strive to make a direct connection with those preferences by letting our prospective clients know that we want to enable them to vacation in their own backyards and come home to outdoor environments that epitomize the good life. In some cases, that means

It's a little too easy to lose sight of what holds the most meaning our work as watershapers - even when it's out there in plain view. In fact, if we're to be honest in assessing the palette of finish materials we use, I think most of us would have to concede that these products can become so familiar that thinking creatively about the full spectrum of their possibilities is something that often falls by the wayside. I believe we should be on guard against