Survey Savvy

Whether it’s done using only a tape measure and a pair of experienced eyeballs or requires the help of satellites orbiting the planet, every construction project is surveyed before the work begins. In fact, surveyors have been plying their trade for thousands of years, and their services have been valued for one simple reason: It’s really a good idea to measure the size and shape of the ground before you try to build on it.

In today’s terms, surveying is defined as the process of taking accurate measurements of the land on the X-, Y- and Z axes (that is, in three dimensions) and then translating that data into a usable (usually printed) format. There are several different surveying methods used to measure, process and communicate this critical information, and choosing the right one is essential to getting any watershaping project off to a sound start.

So how do you determine the level of detail required and communicate your need to the surveyor so he or she can give you the appropriate level of information? Let’s take a look at the different types of surveys in common use and review what those options mean in terms of creating a truly useful array of site-specific data for any given piece of property.

A MANAGEMENT TOOL

As watershapers, we use surveys as a tool not only to initiate a design, but also to foresee possible difficulties in the construction process.

Up front, architects and designers will use survey information to inspire and shape special designs, contours and physical relationships among structures. A bit later on, project managers, builders and subcontractors will pay close attention to survey information to set up access, avoid utilities, understand the limits of cranes and other large equipment and establish site storage and work-flow patterns.

Long before the first shovel of dirt is lifted from the ground, surveys set the stage: They can reveal serious challenges and limitations of a site that relate to the watershape, its design and the overall feasibility of the project; they also carry with them serious implications for the dollars that will be required to make anything happen.

In other words, only with a survey in hand you can provide up-front criteria to a client and/or the project architect so that adjustments in designs and budgets can be made well ahead of any on-site crisis or misunderstanding.

This need for information starts with a basic site survey that indicates site contours and boundaries in detail. Once this basic map has been generated, it guides the soils engineers and geologists and tells them where they need to dig investigation pits or bore into the earth to find the depth of competent bedding material. If there are any questions about anything related to the site, beginning the design process without the information these surveys have to offer would be risky at best.

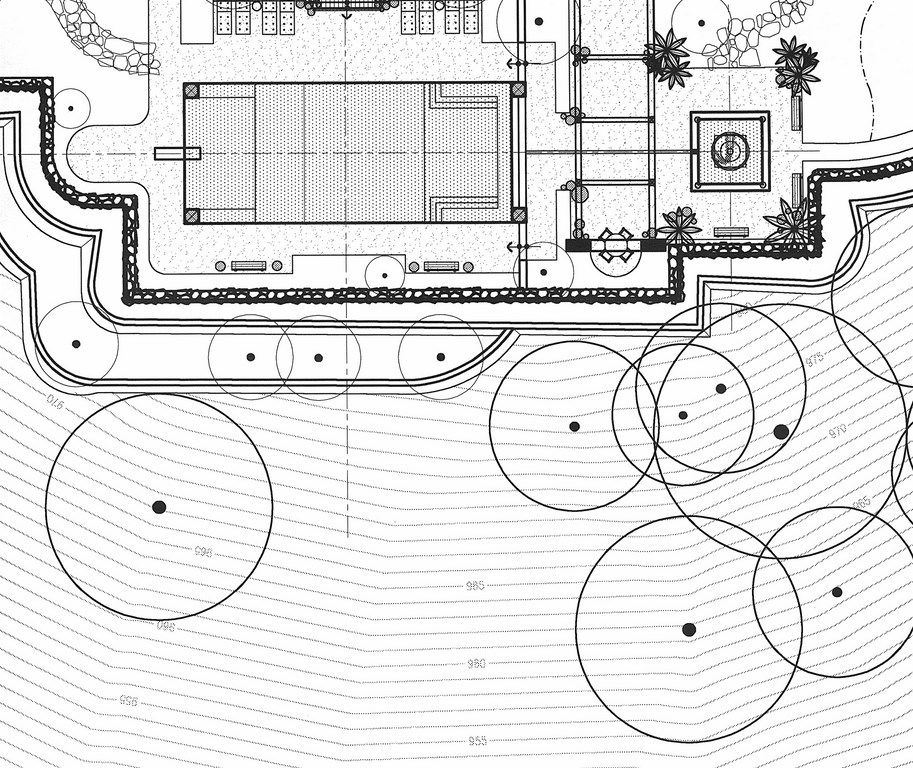

| This pair of drawings shows in clearest possible terms why you need a full set of surveys – topographical, soils and geological – before you can even think seriously about design or construction on a dramatically sloped site. The topographical survey (left) clearly shows the positioning of the proposed pool on a severely sloping hillside. The soils and geological reports showed us what was going on beneath the surface and led us to specify a substructure for the pool with ten piles reaching down as far as 75 feet to competent bearing soil (right). The dashed line seen just beneath the shell in the structural plan is particularly important: It indicates the contours of bedding planes beneath the pool, as indicated in the soils report. Originally, we had thought to have the deep end of the pool oriented the other way. With all of the survey information in hand, we were able to turn the pool 180 degrees at the design stage and saved ourselves lots of trouble by working with the bedding planes rather than against them. |

After all, without these surveys, how can you know for certain where to place any necessary retaining walls, caissons or footings? How can you know whether the watershape requires an extensive substructure – or none at all? How can you accurately determine how strong the structure should be and how much steel a shell needs to withstand pressure from the soil that surrounds it? Basic surveys key the answers to all of these questions.

Bottom line: This is all critical information, and common sense dictates that the more challenging the site and the more ambitious the design, the greater will be your need for detailed base information. That’s where knowing how to match the survey method to your needs comes into play.

WHAT FLAVOR?

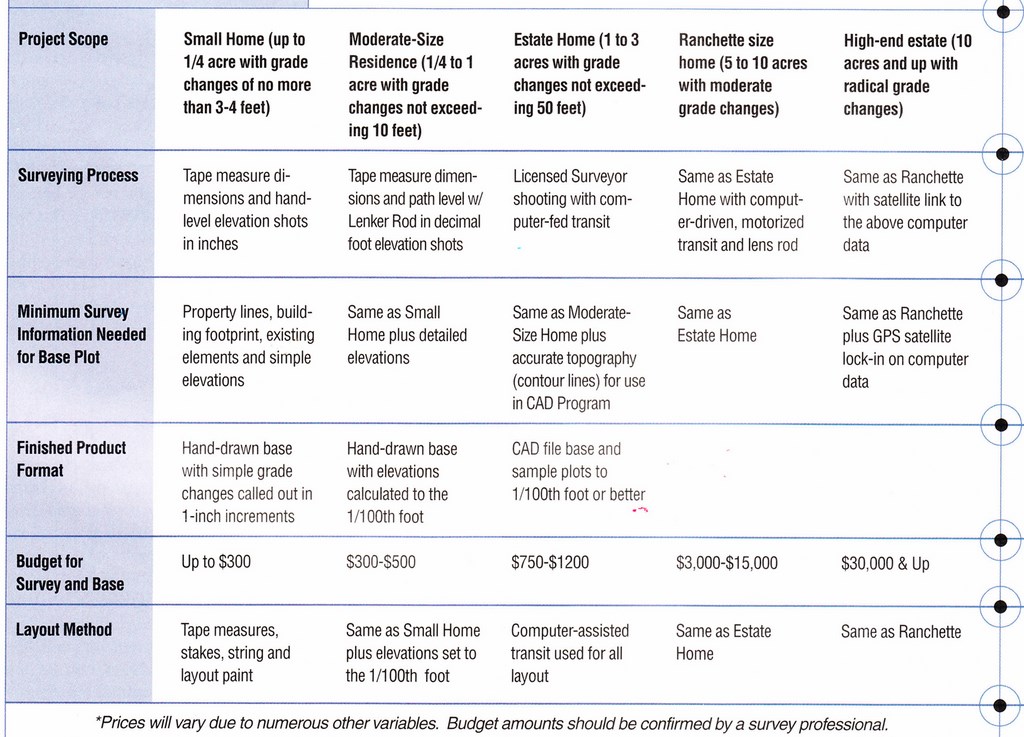

Surveys come in many forms, ranging from simple hand-drawn sketches to computer technologies that are sophisticated enough to guide missiles. The latter is obviously much more costly than the former, so the trick for the watershaper is not to go way beyond what is necessary to get the job done. More important, however, it’s critical to make certain you go far enough.

Among the first questions a surveyor will ask you is: What type of survey do you need? To answer confidently and competently, you have to know a bit about the four basic survey types:

[ ] Hand Measurements: This type of survey usually takes the form of a sketch and can be done by a designer or contractor armed with a tape measure and a sight or path level. Hand-measured surveys are typically recorded in ink or pencil on vellum or paper, and the accuracy is usually to the inch. For the most part, this survey method is suitable only for smaller lots with flat yards and projects with simple designs.

[ ] Formal Surveys: Using an array of complex instruments such as transits, these surveys offer information on dimensions and elevations to within 1/100th of a foot. The finished layout can be either a hand-drafted image or a computer-drafted file, and reliability is greatly enhanced if a professional surveyor is involved.

[ ] Fly-over Surveys: These surveys use photographs shot from airplanes or helicopters. On a simple level, these images allow for highly accurate information on X- and Y-axis data. More advanced surveys also allow for generating Z-axis data through triangulation with existing or known landmarks. A more reliable (and more expensive) fly-over variant is a radar-based aerial survey in which readings are converted to drawings by a computer.

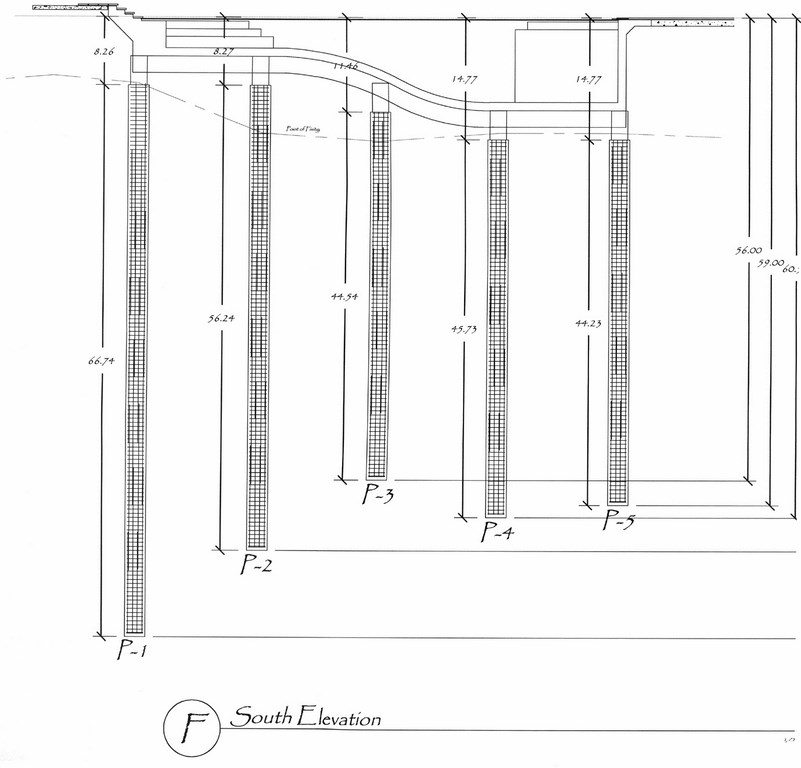

| A good topographical survey makes it relatively easy to configure construction details such as retaining-wall systems – and communicate important information to the crews you call on to install them. |

[ ] Sophisticated Surveys: Through computers, computer-driven data collection devices and synchronized satellite uplinks, it’s possible for a surveyor to provide an extremely detailed layout of any parcel. The cost of all this technology is great and the fees charged by these surveyors can take your breath away, but when it comes to detailed information for very large or unusually complicated projects, these sophisticated surveys can’t be beat.

The computer files generated by these systems start with standard plan views of a project, but you can also tilt the point of perspective, which allows you to fly through a site on a computer while looking at a 3-D model of its topography. The multiple spot elevations shot during the survey process are also translated into a “wire-frame” form that can be rendered into graphic contour lines that accurately denote elevation grade changes in units of one foot, five feet, ten feet or sometimes more – remarkable stuff in amazing detail.

Once you integrate this information into most computer-assisted drawing (CAD) programs, the survey data forms an unalterable base upon which designs are imposed – a most useful feature. And if further surveys are conducted, base data can be updated independently and then transferred into the design file.

RETAINED SERVICES

A professional surveyor also will ask a number of other questions about the job at hand – details that will help him or her plan the survey and estimate fees. In some cases, your answers will suffice. In others, the surveyor may need to visit the site.

Here’s what he or she will need to know:

|

Knowing the Lingo Understanding the basic language of surveyors is useful in discussing your information needs with these professionals. Here are some key terms: [ ] Assessor’s Parcel Number (APN): A code given to a piece of property and recorded with the County Clerk’s office. This information is required for issuance of most building permits. [ ] Benchmark: A beginning or starting point used to set data in a project. [ ] Contour Lines: A line within a survey that encompasses all common points of an identical elevation.[ ] Elevation: The vertical distance relative to a given data point (usually sea level) of a point or object. [ ] Global Positioning Systems (GPS): A navigational and surveying system based on observation of signals transmitted from satellites. Elapsed times for these signals are measured from transmitter to receiver, enabling receiver positions to be computed. [ ] Interpolation: The process of calculating potential contour lines by the use of two or more perimeter points of elevation. This can be used to “guesstimate” topography of an area that is hard to access by working with known top and bottom elevations. [ ] Lath: Thin wooden stakes that surveyors set on a point to communicate a location, signify a boundary or demarcate monuments. [ ] Lenker Rod: A self-reading rod used by an instrument operator. [ ] Path or Site Level: A simple surveying device used to view a measuring stick while maintaining a level field of view. [ ] Transit: A complex device used to measure distance and change in elevation by comparing markers within the instrument to objects in the field. [ ] Topography: The configuration or relief of the earth’s surface, including both natural and cultural features. Natural features include hills, valleys and other irregularities; cultural features include the products of civilization, such as roads, buildings and other structures. — M.H. |

[ ] Lines of sight: The surveyor needs to know if the site can be shot from one location, or if multiple set-ups will be required to cover all of the property.

[ ] Degree of accuracy: How many shots will be taken to adequately cover your needs? Can five or ten shots of the area be used to compute the topography, or will it take hundreds?

[ ] Base detail: How much graphic work is required to generate the base documents? What information will be included in the report? What kind of computer file will be needed?

[ ] Degree of difficulty: Are there any site factors that may affect the surveyor’s ability to shoot the job easily? Is access a problem? Are parts of the property overgrown or filled with debris? Is there any risk of animal attack? Is the soil unstable, or are there any hazardous conditions?

From your end of the conversation, it’s important to know the basis on which the surveyor will be calculating charges. It’s also important to know what rates apply to additional services: Once on site, for example, you may find that you need to survey areas you hadn’t previously considered to get a complete and accurate report. You also need to determine a fee schedule for possible downstream needs such as document reproduction and/or computer time.

Another factor to consider is the fees that will be charged for surveys taken later – that is, as planning and design work continues or once actual construction has begun. After all, once the initial architectural plan has been developed, the design may need to be laid out with the same degree of precision on the site itself.

IN THE FIELD

Before you break ground, the survey information is transferred to the site itself in the process of laying out the watershape.

The simplest form of layout involves tape measures, stakes and string lines to locate “objects” for construction. In some cases, however, and especially when greater control is required for more complicated projects, computer-driven equipment is often used to transcribe the design data into real-world points in space.

Some surveyors use tripod-mounted computer guns that take information downloaded from the CAD system, pre-designated with X, Y and Z data. These instruments alert the surveyor when the lens-mounted rod is in the correct spatial point on the site. The surveyor then marks this location with a pin or a piece of lath. With this type of system, the survey professionals can find any point during the construction process by simply re-accessing the numeric code for that particular location.

| The existence of competent surveys simplify tasks such as excavation by giving the excavator’s crew precise guidelines, but real performance on site requires steady supervision of the dig and regular reshooting with surveying instruments to make certain all significant dimensional details end up hitting their marks. |

Such a system provides a mechanism for steady checking of base survey information to ensure that important construction dimensions have been observed at their precise locations within the site. This is especially important when changes are made in the course of construction: It makes it possible to determine whether any alterations have affected areas that were not to be changed.

In essence, surveys are a tool with which every watershaper should be familiar. They offer assurance up front that a design will work in the context of a specific site. In the course of a project, they give the watershaper assurance that work is moving forward accurately and within specifications. From the simple to the sophisticated, they have a primary role in any and every successful watershape installation.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at mark@waterarchitecture.com.