Constrained Expanse

In the course of my career as a landscape architect, I’ve had the good fortune to work on the full range of possible projects, from residences to commercial and institutional properties and in spaces ranging from the compact to the vast. Through all of this experience, I have to say that working on botanical gardens, in whole or in part, has been about as satisfying as it gets.

The first two articles in this three-part series have demonstrated some of the potential these facilities have to engage a designer in special ways: First, the projects are very public and focus the mind on working with the diverse constituencies these projects must please, from boards of directors to first-time guests. Second, they give the designer an opportunity to learn more about specific (and often amazing) plants through association with experts who may have forgotten more than the average landscape architect will ever know about certain species.

Third, and I won’t belabor it here, the work is personal and soul-satisfying in unmatched ways. To me so far, these projects have signified an acknowledgement that I’m good at what I do; they’ve given me opportunities to participate, learn and teach garden visitors about plants I’ve come to love; and, finally, they’ve let me express myself, my design philosophy and my artistry in ways few other projects do.

The Miami Beach Botanical Garden is an embodiment of all of these virtues, values and qualities and in many ways offers the perfect means of bringing this trio of articles to a close. And I haven’t yet mentioned the challenge: This particular garden space is tiny, with nowhere and no way to grow.

ODD ORIGINS

Founded in 1962, what was eventually to become the Miami Beach Botanical Garden was plunked down on a stray, oddly shaped parcel that stood across the road from what was then the recently completed Miami Beach Convention Center.

Originally designated as “The Garden Center,” the facility had been built on the site of an old golf course and rode along through the 1960s and ’70s with the city’s growth as a tourist mecca. But it was never much of a focus and deteriorated through the 1980s, bypassed by the city’s Art Deco renaissance and then slammed by Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

The turning point came in 1996, when the Miami Beach Garden Conservancy approached the city with a restoration proposal – and the city accepted. The program slowly gathered resources, and we at Raymond Jungles Studio (Miami, Fla.) came aboard in 2011 to help create what the garden’s board defined as a dynamic venue for the arts and cultural programming as well as for environmental education and cultural tourism.

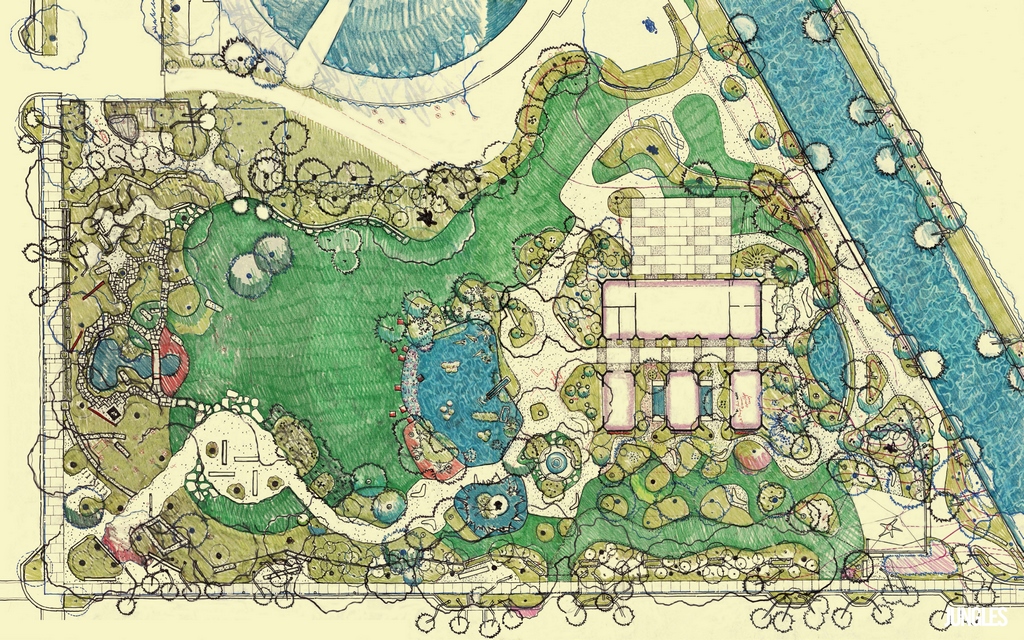

| The garden space we were asked to revitalize was truly small, shoehorned into a rough triangle across from Miami Beach’s convention center and offering no room at all for growth. It had been in decline for years by the time we arrived, but we recognized that it had good bones and a great plant collection. |

The main limitation the garden has always faced is that it’s hemmed in on all sides and has no means of growing beyond its current 2.6 acres or its thin budget. What we proposed was quite straightforward: We wanted to narrow the focus to native Florida plants and trees and become excellent within a limited scope rather than stretching thematically beyond what the property’s physical limitations would allow.

At the same time – and as was discussed in detail in the second article in this series – we know that botanical gardens are businesses, pure and simple. So, based on past experience, we included special, dedicated areas meant to draw crowds on their own or to create venues for activities that would bring more patrons (and event-space renters) through the turnstiles.

| To expand the visitor’s perspective on the available spaces, we used turns in pathways and changes in paving materials to introduce illusions of distance, sensations of variety and an abundant air of adventure. We also set up special destinations, including a diminutive Japanese garden, large lawns and seating areas that served the needs of small groups as well as couples and solitary visitors. (Photos by Steven Brooke, Steven Brooke Studios, Coral Gables, Fla., and by Stephen Dunn, Stephen Dunn Photography, Santa Fe, N.M.) |

In other words, while we included bromeliads, palms, cycads and orchids to appeal to lovers of Florida’s native plants, we also mapped out a small Japanese garden as well as a number of waterfeatures – ponds, fountains and a wetland filled with mangroves and pond apples – while expanding the lawn area for corporate and social events and adding lighting systems so the gardens would be safe, accessible and usable after dark.

In accepting the commission, we adopted the garden’s full mission: to promote environmental enjoyment, stewardship and sustainability through education, the arts and interaction with the natural world through a subtropical oasis of beauty and tranquility within an urban setting. Along the way, we intended in every way possible to develop a community resource meant to refresh, inspire and engage all comers.

NATURE’S BOUNTY

The renovation was funded and managed by a public/private partnership between the Miami Beach Garden Conservancy and the City of Miami Beach, and our initial focus was on compensating for the facility’s limited size by accentuating its tremendous botanical diversity.

We pursued that goal while defining distinct functional areas – gathering spaces, spaces for contemplation, intimate spaces and public spaces – and making the most of what was already there. This included repurposing certain elements of the existing garden to give them more visual punch while also setting up a variety of garden “rooms,” each with its own character and energy.

We began our work at the entry, turning it into a procession through spaces that preview multiple possible experiences garden visitors might have. As was the case with the Naples Botanical Garden, we also opened a long sight line for those passing through the gates, suggesting a boundless space beyond.

| The larger gathering spaces serve the garden’s commercial interests by enabling groups of different sizes celebrate weddings or corporate events. The spaces are also structured to host school groups, garden tours, and visitors who come for no other purpose than to stroll through the plants, sit on benches or experience the garden’s multiple bodies of water. |

And as with almost all of my gardens public or private, water is a key element here, as it has been in my other botanical-garden projects. In these environments, start with the fact that water plants substantially expand opportunities to express diversity. Then move on to consider water’s value in providing essential open space – places, for example, to interact with and appreciate water’s reflective qualities.

In that context, water welcomes the sky into the composition, animating the space and – very important in this compact context – mirroring and thereby expanding the visitor’s perception of the scale and scope of the landscape. And in South Florida, it’s impossible to overlook the benefits of water’s ability to cool its surroundings, especially when the water moves.

| In setting up access to the garden’s ponds, fountains and waterfeatures, we considered the paths by which visitors would approach them and made certain that these scenes unfolded gradually as people followed paths that ultimately brought them to the water’s edge. Once visitors reached these destinations, we made just as certain that views at their feet as well as across the water were just as varied and visually rewarding. |

Water’s openness also aids in the process of setting up clear links and visual transference across garden spaces, thereby helping us blur the sense that any one area is dedicated to this sort of plant while the ones next to it are about other plants. That sense is further broken down by reflections and long views across the water that broaden visual fields and embrace multiple planted areas and their varied colors, textures and degrees of physical presence.

But this is also quintessentially an instructive urban environment in which the garden offers a sanctuary for native fauna as well. By layering plants together in key areas, we offer visitors spaces where they can look out for birds, insects and other creatures drawn to both water and plants.

And, happily, the palette the garden’s growers and plant specialists presented me with was huge, so I was able to draw on flowering trees, palms, cycads and other subtropical species that had what it took to fill the garden with great beauty and utterly amazing diversity.

THE DRIVE TO THRIVE

Building on my past experience with botanical gardens, I also involved myself in the overall physical layout for the Miami Beach Botanical Garden and weighed an array of functions that have been parts of other public-garden spaces I’ve come to know intimately.

In this case, for example, I recommended some upgrades for the facility’s buildings to make them part of the revised space with respect to color, texture and style and suggested several changes to the entry area that promoted more active circulation of visitors and staff through the common area just past the gates, thereby suggesting activity and making the promise of moving out to quieter spaces beyond a key part of the program.

We also moved the plant nursery/propagation area away from the entry to a remote corner of the garden, reducing visitors’ immediate contact with spaces most botanical gardens prominently label as being “off limits.” With improved circulation – both artful and practical – the garden is now able to schedule multiple and simultaneous events on its grand lawn and peripheral terraces while also still offering spaces for meditation or quiet conversation.

| Using the water’s reflective potential was in many ways the key to making the Miami Beach Botanical Garden seem far larger than it actually was. From every angle and no matter whether the visitor is looking across a large body of water or is close up to one small area, we brought plants close to the water to ensure an impression of approaching infinity. |

These changes have increased the potential for generating revenues through rental of meeting spaces and have also set the stage for garden-centered events, including an annual “Taste of the Garden” gala as well as weekly green markets, in-garden yoga sessions, theatrical performances and private wedding receptions.

My pathway to appreciating this potential with botanical gardens has been shaped through decades of experience in communicating and negotiating with garden administrators and staff and by spending a substantial amount of time observing the way visitors – both garden regulars and occasional guests – move through and use these spaces. I have learned how to meet all these diverse needs and at the same time have continuously built my own knowledge base with terrestrial and aquatic plants from a range of subtropical sources.

It’s been a great ride and always has me on the lookout for new opportunities to dig in and get involved in what I consider to be the crowning achievements in any landscape architect’s career.

To see the first article in this series – on my work at the Fairchild Tropical Botanical Gardens and the Key West Botanical Garden – click here. For Part 2, on the Naples Botanical Garden, click here.

Raymond Jungles is founder and principal of Studio Jungles, a landscape architecture firm based in Miami, Fla. His prime inspiration and the key to his passion for landscape architecture stems from his longtime relationship with Brazilian artist and environmental designer Roberto Burle Marx, and his current practice is firmly rooted in Florida and the Caribbean basin with a focus on residential, resort and community design. For more information, visit raymondjungles.com.