Shimmer and Shine

Looking for a surface material as unique as the resort itself, the designers of Jade Mountain turned to David Knox of Lightstreams to create completely original tile products for use in the structure’s 25 vanishing-edge pools, with each one to have its own unique colors and optical qualities. Here, Knox describes the process of deploying glass tiles throughout one of the world’s most unique and extensive watershape environments.

For me, Jade Mountain is not simply a resort in St Lucia: It’s more of a spiritual and artistic achievement – and one I helped fashion through a period of 15 months.

I felt that sense of operating on a higher plane during my first visit to the parent resort, Anse Chastanet, in March 2005. There was something different about the project, just as there was

something unique and fascinating about the owner/architect, Nick Troubetzkoy, and his design team: I could see it their eyes, I could see it in the building, and I could hear it in the stories they told me about the project.

I listened to tales of the ten-year project and the endless evolution of its design; I also heard about the self-sufficiency and improvisational necessities forced upon their efforts by the island’s isolation and limited resources. To a person and through it all, they believed in Jade Mountain even though they did not know exactly what it would look like when complete or how exactly they would get it done.

When I first became involved, in fact, the project didn’t even have a name. As recently as two years ago, Karyn Allard, the project coordinator, was still referring to it as Silver Cloud, which had been Troubetzkoy’s code name for the emerging concept. The only certainties were that it was happening and that they would somehow get it finished.

Once involved, I suddenly found myself in the same sort of personal voyage: I had produced a prototype glass tile and had been given the go-ahead, but at that point I had no clear idea how I was going to produce it in the mass quantities of tile that would be required and that I was now committed to making. All I had was a single piece of glass I had finished the day before I left for my first visit.

NO ILLUSIONS

If you read my article in the June 2006 issue of WaterShapes (“Light Dances,” page 50), you may recall that I have a background that includes 20 years of laser and optical-system design and development.

As a consequence, I see light in mechanical terms as a limitless sea of tiny, invisible balls of photonic energy that appear to us as color only when the balls decide to dance together in a wave. The cones and rods in our eyes are able to perceive those waves of light when they range in physical length from 400 nanometers (violet) to about 800 nanometers (red).

I’ve spent my professional life consciously manipulating these infinitesimally small balls of light so they dance together in waves to form specific colors. In the laser industry, our goal was to create very narrowly defined waves – what is known as single-mode operation – to produce only one exact “color” at any given time. (Imagine formal military brigades marching in lock step.)

| The tile for Jade Mountain is all made in a way that allows observers to see fascinating color changes across large sections or fields. It all depends on lighting and the observer’s angle of view, and even reflections of tile bands at the waterlines of various pools can be completely different from the source of those reflections when the timing is right. |

In making glass tiles, the goal is very different and is about making light dance in many waves to produce ever-changing colors.

My design vision for Jade Mountain was to create a tile that would be well balanced in reflecting and transmitting light while being randomly prismatic. In layman’s terms, I wanted a certain amount of light to pass through the glass and a certain amount to reflect back from its front, back and internal surfaces. I also wanted the glass to create different colors at different viewing angles (just as a prism creates a rainbow), but I wanted that phenomenon to operate in an unpredictable manner so it would always be surprising.

If I could achieve this optical design, I was reasonably certain the resulting fields of tiles would have what I call day and night moods: a colorful, shimmering bikini by day and an elegant, black cocktail dress by night. The pool water would also act to optically amplify and synthesize the effects, the result being a living floor of watery, moving color.

While I metaphorically thought of the new glass as a radiant, transparent stone, I did not realize until masses of it were assembled just how much it actually looked like transparent stone. The fundamental design assured not only achievement of the random prismatic effect I desired, but it also guaranteed that each and every tile would be unique in terms of texture and appearance, just like natural stone.

NATURE STUDY

Spending a week at Anse Chastanet gave me time to get a feel for the environment and a good sense of the light and native colors.

Our hosts aided in our assimilation of those details by having us stay in a couple of different guest rooms to get a feel for architectural style and the overall mood of the resort. This was important, because each room – every one of them huge with open showers, beautiful woodwork and private views – was entirely unique, a characteristic that would be crucial to the program for Jade Mountain.

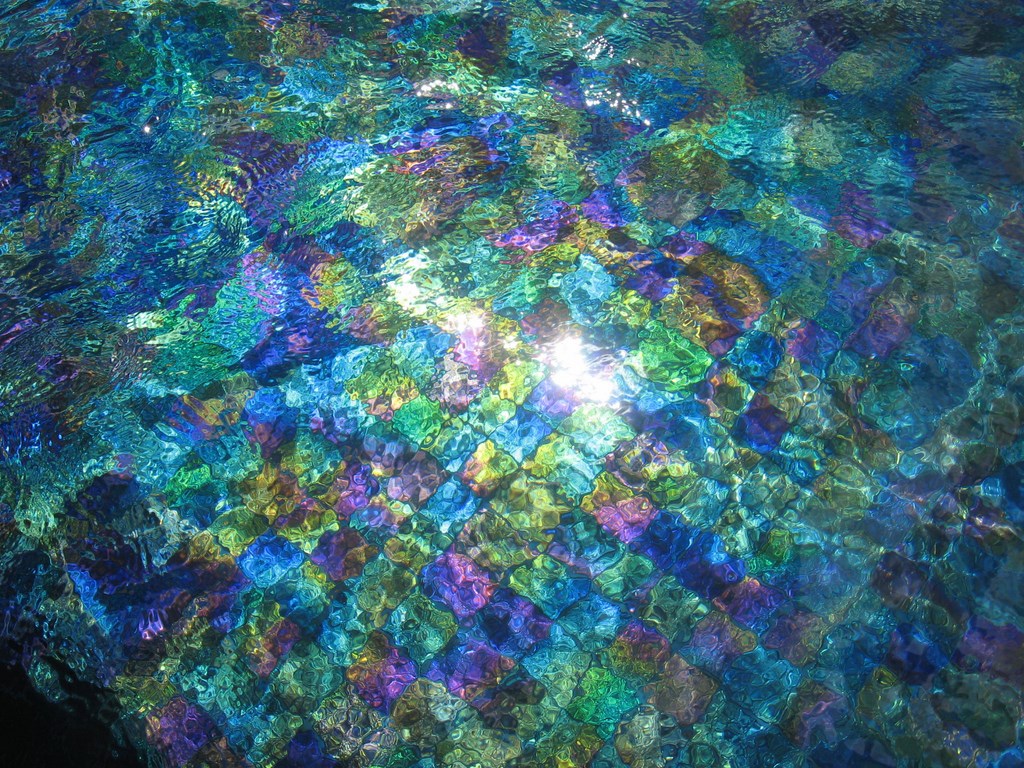

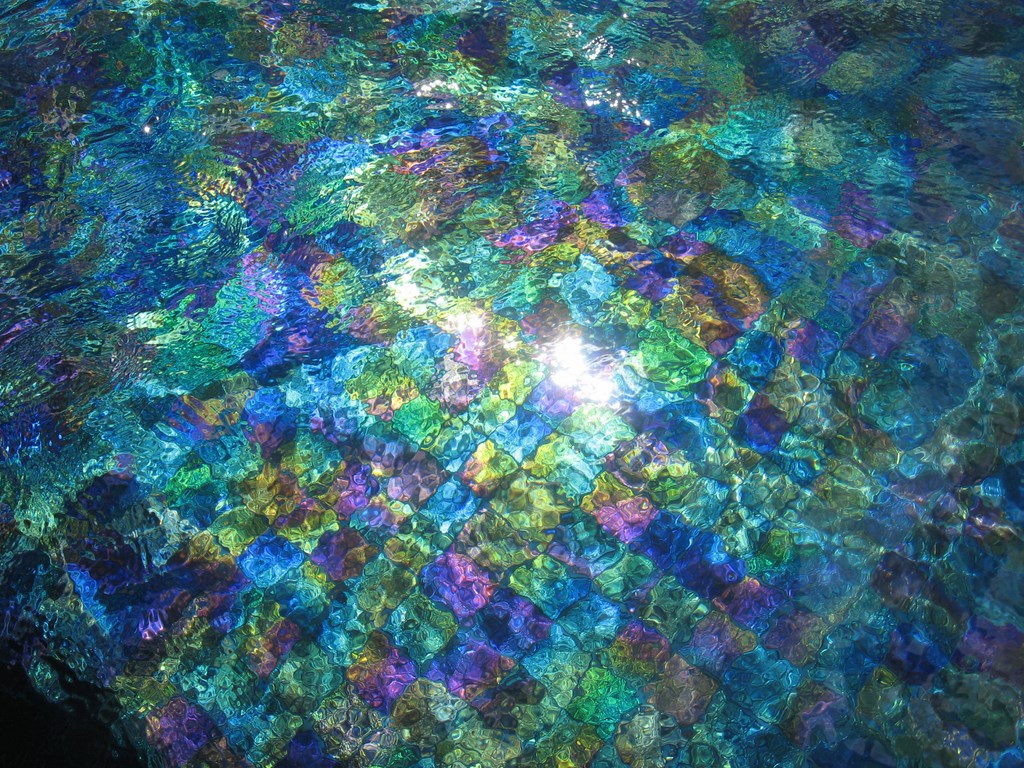

| The transformations in appearance can be quite impressive. Here, for example, the deep-purple tile of this pool becomes a patchwork of dozens of colors when the viewer looks on from the right angle at the right time of day. |

While there, we met daily with the staff of architects, designers and project managers in both formal meetings and casual social gatherings. In a project of this scope, we all shared the sense that it was important to know each other and, in my case, become comfortably familiar with the project’s goals. I devoured everyone’s stories and spent a good bit of time with Troubetzkoy, developing a sense of his artistic philosophy and observing what he had already created.

Quite frankly, I had never seen any project on this scale that was as organic in execution as this one. It was the antithesis of the staid architectural process of endless documentation and meetings, and I soon developed the sense that Jade Mountain was more a sculpture than a building to Troubetzkoy. It would, I felt, be his masterpiece, a vision that was hard to convey to others because it was based in feelings – more a primal utterance than a blueprint.

| In still water, you can actually see the internal and surface reflections within the glass as the light skips across the surface but also glows within the glass. When the water is rippled, the optical effects are magnified and synthesized by the water, producing spectacular (but momentary) shimmering fields. |

As we came to know one another, Troubetzkoy and I also discussed my optical designs and my aim of balancing transmission and reflectance of light in the glass. In the bright sunlight, we both saw as the deep blue-green color of the prototype tile became saturated and appeared very transparent, a trick of vision that changed the amount of reflection from the textured, iridescent surface.

I could see a light go off in his head: From that moment forward, he understood the nature of my work in glass, understood how and why each color would be affected differently by the light and had a keen eye for how he would design with it. Things moved fast, and we began to sort through the potential palette with a new understanding of what was to come.

We all began to see that the prototype – just an isolated, detached piece, after all – was in fact becoming more optically dynamic and radiant the more we studied it. It was truly exhilarating, and I proposed using the prototype formula to create a palette similar to the palette his watercolor renderings of the building had used. The goal was for each of the 25 rooms to have its own color.

FLYING CARPETS

With only that single prototype tile in existence, the project commenced.

Before we finished, it would encompass 27,000 square feet of custom glass tile in two dozen different colors, all to be delivered within six months of final color selection. I went right to work creating samples, made a few adjustments to the textures and, within six weeks, everything was settled. We named the final glass design for the project our “PNT formula,” the initials standing for Prince Nikolai Troubetzkoy to honor his heritage and official title.

My vision for the glass-tiled pools was that they should appear as watery, oriental carpets of light floating in space – surreal tapestries of color that would entertain the senses without competing with the magnificent, omnipresent views of the Pitons just beyond each room. The pools were to be subtly dynamic as a counterpoint to static presence of the awesome green mountains.

| The outcomes of these visual transitions can be spectacular. In this avocado-green pool, for example, you can see inklings of something beginning to happen in this view of the top step. With a simple turn of the head, the vanishing-edge wall becomes a blaze of dancing color against the visual solidity of the wooden coping and the stone deck. |

Individually, each glass tile is a complex optical element that manipulates light in a sophisticated manner to create colors. As laid out collectively at Jade Mountain, however, I created a field effect by having the tiles operate as a visual whole. On that level, Jade Mountain may be the world’s largest installation of optical, environmental art fully integrated into its surrounding architecture.

While utilitarian in purpose, each tile field is much more a statement of color than a simple surface finish. And again, it’s about counterpoint: The tiles are one of only five surface finishes used in the resort, the others being exotic hardwoods, coral-stone tile, natural rock and cast concrete. The colors of those materials operate in a limited range, opening the door to brilliantly colored juxtapositions with the glass tile.

The chameleon-like color changes we achieved throughout the building are unlike anything most people have experienced.

They have been described as both mesmerizing and elusive, like a beautiful fish moving through the water except that the beautiful fish can suddenly transform into an incredible school of fish amid a patchwork of colors. Moments before of after, the colors can also be simple and static in a state I call their “dormant phase.” The shifting back and forth from dormant to dynamic is constant and fleeting, an active dance of light in which the viewer participates by viewing the fields at different angles.

MOVING IN LIGHT

By design, each piece of glass tile we produced for this project is both completely unique and fully reversible. While each four-by-four piece of glass tile is beautiful and offers its own unique optical choreography, however, the art comes when the fields of tile work together. They are all transparent, but one side has a textured iridescence and the other a smooth finish with a mildly undulating surface.

The iridescent side of the glass was used exclusively on the pool’s surfaces, while the smooth side in the same color tiles was arrayed on the walls of the open bathrooms. Every piece was done in a four-by-four-inch format to give us large optical apertures for capturing light while reducing the presence of grout lines. Stylistically, we wanted the look to be far removed from that of conventional glass-mosaic tile.

At base, what we were after was about more than the tiles or even the apparent colors of the tiles. Instead, the work was about what the tiles would do to the light – about how they would manipulate the endless stream of invisible balls of primary, cosmic energy that constitute light. In doing so, we assembled a bold collection of colors, from avocado green and ruby red to purple, emerald, bronze, root beer and deep, deep blue – but the specific colors are more the spirit or mood of that color than a definition of it. The tiles change the light, randomly and constantly, and make it dance in waves of color.

| The pools and their tile also work into the overall design scheme for the rooms, with the tonalities of this ruby-red version picked up in the furnishings and even the plants. But there’s always another view available, another angle that changes the scene and puts everything in a new context. And sometimes those effects are both dazzling and mesmerizing. |

Each field is centered in the static, dormant color (Chinese red, lime green, medium blue and so on), but more accurately, the base color is a point of departure and return for a dance that spans a wide and highly detailed spectrum of colors. In creating them, I hoped to capture the sublime and elusive spirit of the island itself and create a subtle, mystical experience for Jade Mountain’s guests.

The mystical part of the composition is how the colors move and exactly when and where they really exist. In other words, unlike fish who swim through the water and thereby change reflected angles of light with their movement, the tiles are perfectly still, mortared firmly to each pool’s surface.

This is the instant-by-instant nexus at which the experience becomes magical.

The colorful movement one experiences with these pools is the result of the light that the glass gathers and manipulates as it reflects back to our eyes. No significant movement by the viewer is required for the field to operate visually: It just needs light and an eye to observe it. The clarity and complexity of the glass design permits even the slightest change in either light intensity or viewing angle to alter the composition, sometimes dramatically.

SIGHT SPECIFIC

To be sure, the shimmering fields of color produced by the tiles are beautiful, but just as important to the overall design is their ability not to shimmer – a visual dormancy that is indeed critical to the design.

The dormant phase – that is, moments when the pools just look like the basic color of the tile – is driven by the eye’s viewing angle and the angle and intensity of the ambient light. Had I designed the glass to be apparent and mind-blowing all the time, the pools might have become a visual distraction.

| The royal-blue pool is among the most remarkable of all the watershapes on site. You get a hint of what’s going on away from the pool, where the tile on the wall of the bathroom begins to reveal the dormant tile’s potential. When the light and angles are right, the view across the vanishing edge completes the picture for anyone and everyone to see. |

A sunrise is special because each is unique and momentarily beautiful. With that in mind, I designed the tiles so they would not overwhelm, but would instead fascinate – a subtle distinction that leaves most guests unaware of the intricacy of the experience but still filled with a sense that, for whatever subliminal reason, it feels good. That is precisely the effect for which I was hoping: a sense of well being, not a sense of distraction.

In going into some detail on the effects the tiles achieve, I may have gone too far and explained away their magic: After all, the show at Jade Mountain is not the tiles or the pools or even the amazing building. Rather, it’s about the environment as a whole, the tropical backdrop, the warm, fresh air and the perpetual visual wonder of the Pitons.

It would have been far easier to create conventional tiles that predictably reflected light the same way every time, but I was fully aware that Jade Mountain would have no televisions, no phones, no elevators, no windows and no fourth walls and that we were creating incredible, magical environments amid a timeless, indefinably organic architecture.

In that sense, the pools are like orchestra pits sunken a bit below a great stage, emitting symphonies of light in meditative homage to and in transient reflection of a compelling world beyond.

Just amazing.

David Knox is president and founder of Lightstreams, a manufacturer of specialized glass tile in Mountain View, Calif. He earned bachelor’s degrees in art history and American studies from Connecticut College in 1978. Following stints on Wall Street and beyond, he established Directed Light, a laser-systems development and manufacturing firm in San Jose, Calif., and pursued additional studies in mathematics and optics. During the 1980s and ’90s, the company made lasers for a veritable “who’s who” list of major technology firms, including Hewlett Packard, Motorola, Raytheon and Hughes Aircraft. He sold the firm in 1998 and continued to consult for the laser industry until 2002, when he changed career directions and began applying his knowledge of lasers and optics to the manufacture of glass tile.