Seeking Perfection

Through the past two years, a handful of voices in this magazine and elsewhere have called for building pools without drains as a means of virtually eliminating suction-entrapment incidents. The response to this suggestion has been strong, both for and against.

In sifting through some of these discussions – including a key interview with Dr. William N. Rowley that appeared online last fall on the WaterShapes Web site – one item caught my eye: It came from a watershaper who clearly didn’t have a horse in the race but simply wanted to know how to go about building an efficient pool without a suction outlet at the deepest point of the floor.

Good question, I thought, which prompted me in taking my turn at writing “Currents” this time to offer a drainless design that meets the needs for proper circulation while making pools and spas as safe as possible.

TIMELY IDEA

For my own part here, I don’t mean to be argumentative. Instead, I’m just offering suggestions based on my long experience with the issue, and I do so because I sympathize with those watershapers who are less interested in debating and would rather focus on finding and implementing a reliable solution to the problem.

In conducting countless safety inspections, I have personally seen that every single entrapment-protection system ever devised can be (and quite frequently are) damaged, disengaged, altered or removed by a service technician, a pool operator or a homeowner. Likewise, drain grates seem to become old or cracked or lose their screws and for whatever reason seem to be subject to frequent removal. For their parts and despite the good intentions or designers, specifiers and builders, pumps are too frequently sized improperly.

And all of this – all of it – is aggravated by the fact the pool/spa industry has an amazing capacity to resist change, no matter how crucial the issue might be to its ongoing prosperity. Then there’s the fact that the design community (meaning landscape architects and architects) have the ignoble habit of ignoring water-related specifications. Topping things off, there’s also the fact that, in residential situations, even the regulators themselves have a pronounced tendency to ignore codes and seemingly make things up as they go along.

Making real change in this context is, I think, all about coming up with a model – an example toward which we should all be striving – and then tailoring the regulations to fit that ideal.

I am enough of a realist to know this will not happen overnight, but I am also one who feels an obligation to lead by example. As a result, I have started designing and building in such a way that the risks to bathers are demonstrably and dramatically reduced – to such an extent, in fact, that these watershapes go well beyond what any health department has ever required to date. And I apply the same principles in residential pools as I do in commercial and institutional projects.

Here’s hoping that this approach, which I’ll describe here, helps some of you handle these issues in safe, sensible ways.

My aim here is to fuse the most advantageous products and techniques available into a comprehensive program that never lets the viability of any single object or measure within the system determine whether a pool or spa is safe. As I see it, my approach is analogous to the use of seat belts: On their own, they do not make driving entirely safe, but when used in combination with airbags, crumple zones and good driving habits, they can work wonders.

This is why, as many others have suggested, I start by eliminating the drains themselves: They are beyond doubt the most dangerous of all the pool/spa components involved in entrapment incidents – and there’s no need for them to be there at all!

WALKING A NEW LINE

Indeed, the only argument in favor of continuing the use of drains is that they are needed to ensure proper water circulation. Although some argue strenuously that this is simply not true, let’s assume for the sake of this discussion that it is. I, for one, recognize that if you leave the water in the bottom of a pool stratified and basically uncirculated, you’re inviting all sorts of problems with bacteria and algae – not to mention a distressing appearance.

In that light, it seems the key in removing the drain is to make certain we alter the way we circulate water in a pool. The obvious thought here is to return water through the pool’s floor – a common approach in competition and public pools that should be used in all residential pools. Not only does this positioning of inlets improve circulation, but it also improves heating efficiency and ensures better distribution of sanitizing agents.

If drains are deleted from our watershapes, skimmers will by default become the primary suction devices for all pools and spas. There’s a problem here, of course, because most builders run too much water through them and don’t do a good job of handing equalization. Happily, there are easy solutions on both fronts.

Most skimmers are rated by the National Sanitation Foundation (NSF) for a maximum flow of 55 to 75 gallons per minute, so I would suggest that the code writers need to develop a firm rule that all watershapes designed for human immersion should have a minimum of two skimmers. That would be the rule for pools with capacities up to 30,000 gallons (with maximum six-hour turnovers), after which another skimmer should be required for each additional 18,000 gallons.

As for the equalizer lines that are activated when low-water conditions render skimmers inoperative, they all need to be split and set up in walls with grates a minimum of 48 inches apart. In addition, they should be rated with minimum 100-gallon-per-minute flow capacities at each grate. That way, in normal low-water situations, there will be a theoretical maximum of 25 gallons per minute running through each grate when it is not covered in an entrapment situation.

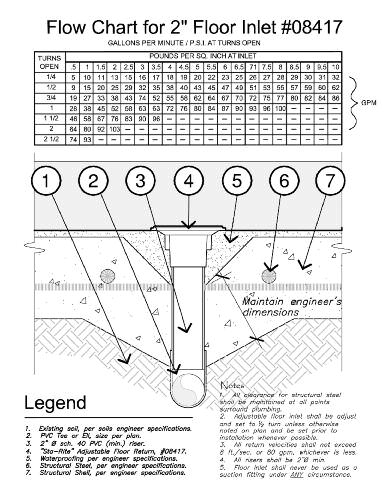

Floor returns (also NSF-rated) must be at least four in number for the first 400 square feet of surface area, with another return added for each additional 100 square feet of surface area. These units should be rated with minimum flows of 25 gallons per minute. And I would suggest that simple flush-cut pipes should not be used, as toes might be ensnared by them.

THINKING DIFFERENT

This fresh approach in no way relieves the designer or installer of the responsibility of observing sound hydraulic practices. For a variety of reasons, I believe velocities should be lowered in all watershapes meant for human immersion. In fact, I would set the upper limit at suction points (that is, at the skimmer and equalizer lines) at a maximum of five feet per second and at discharge lines of no more than seven feet per second. Not only will these levels minimize any opportunities for hair or limb entrapment, but they will also substantially improve equipment efficiency.

In this context, the use of variable-frequency-drive pumps is much to be desired. Many of them now include integrated SVRS devices, thereby further limiting entrapment hazards while also minimizing energy consumption. Frankly, the use of these pumps simply makes sense in a marketplace in which hydraulic systems are rarely designed with accurate assessments of horsepower needs in hand. Once these new pumps are set and locked, both safety and energy efficiency are improved.

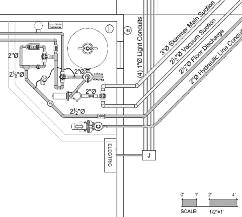

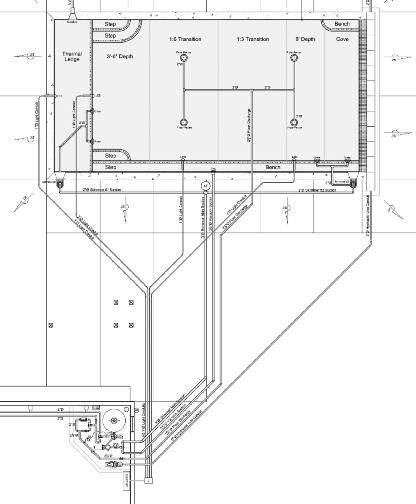

The accompanying illustrations (just below) offer an overview of how such a system might look. As has always been the case, there are numerous possible ways to achieve similar results. The idea here is to focus on the desired outcomes and then back up to define the systems needed to support those outcomes without hesitation or compromise.

Have no doubt that these systems are real: I’ve been using these concepts myself in recent projects; all of the components are readily available; and I have never been surprised by the fact that this new angle on what I do is producing watershapes that are more efficient as well as safer.

Have no doubt that these systems are real: I’ve been using these concepts myself in recent projects; all of the components are readily available; and I have never been surprised by the fact that this new angle on what I do is producing watershapes that are more efficient as well as safer.

| Here’s a plumbing plan for a pool without a main drain, including a detail for the equipment room. I’ve used this approach in recent projects, and it has the advantage of using readily available components – although perhaps in unconventional ways. |

The whole principal of this new breed of watershape – this thing I call “The Perfect Beast” – has to do with designing and building the best pool possible rather than the easiest or cheapest. As I see it in these difficult times, improving and indeed completely altering the reputation of our industry to everyone’s benefit calls upon all of us to rise above minimums and start striving toward maximums.

If I had my way, every single residential pool and spa built henceforth would represent the pursuit of the ideal and compliance with a stringent new set of rules that leaves none of us with more than a few shreds of wiggle room. I know the very thought of more regulation offends the sensibilities of a great many watershapers, but my assertion is that doing things in accordance with this new model makes the process simpler to follow and dramatically increases the safety of our products.

Swimming back to my automotive analogy, driving in traffic at high speeds without the protection afforded by seat belts, air bags, crumple zones, antilock brakes and any other available car-safety feature now seems unwise. Driving a short way over to pools and spas, it seems similarly unwise to swim in a pool or lounge in a spa that lacks any of the safety features I’ve mentioned.

FORGING AHEAD

It’s true that people don’t like change, but what does that matter if our clients can be safer when they bathe or swim? What’s so appealing about angry threats, regulations and lawsuits that make people cling to the past? It may be true that there’s easier money to be made by working in familiar ways, but experience tells me there’s even more to be made by doing things differently and facing the fact that substandard work will chase you well beyond the day you finally leave (or are driven from) the business.

| This chart shows the effects of tuning floor returns to provide the flow characteristics needed to maintain balanced circulation. Again, these aren’t unfamiliar components: It’s just that we need to look at them in new ways in a drainless context. |

I’ve said many times in this space that it’s time to move forward, and I’ve asked those who disagree with me to register their reactions by writing letters to the editor. As yet, nobody has told me why this approach to safer watershaping should not be law. Now that I’ve spelled out my position on this concept of a drainless pool in even greater detail, I’d be happy to engage in a discussion of the merits or deficits of what I propose and keep this dialogue going.

I am convinced, based on conversations I’ve had as well as work I’ve examined, that lots of you out there agree with me. As I see it, those of us who’ve adopted these approaches and techniques, even if only in part, also have an obligation to stand up and be counted, just as surely as those who disagree with me need to stand up and defend their positions.

And if there is no opposition and everyone agrees with me, why is anyone still talking and why isn’t everyone eliminating drains from their designs?

These days, I don’t think we have the luxury to stand still and wait for things to unfold around us: The future of what we do is literally at stake, and if we want to prove ourselves worthy of the role we’d like to have in bringing physical fitness, physical well-being and joy to those who own and use our products, I can’t think of a better time to settle this discussion.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect and a landscape and pool contractor specializing in watershapes and their environments. He has been designing and building watershapes for more than two decades, and his firm, Holdenwater of Fullerton, Calif., assists other professionals with their projects. He is also an instructor for the Genesis 3 schools and serves on the faculty at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona. He can be contacted at mark@waterarchitecture.com.