Searching for Style

Among the most complicated tasks you’ll encounter in designing a watershape is determining your clients’ style and how it applies to the project.

How important is it to know what style they want? That’s a complicated question, because style is highly subjective. It’s also an important one and can, in fact, make or break your design and your relationship with your clients.

How do you determine what they want? You can always start by asking them, but very few clients will tell you, “I want this style watershape with this style landscape, and I want you to use these plants” – and conclude by handing you a plant list. So let’s take a look at what style means, then explore how it can affect your work as both designer and contractor.

WHAT IS STYLE?

Webster’s dictionary defines style as “a manner of expressing thought in writing, speaking, acting, painting, etc.” What this means in the case of watershapes is that your creation should be an expression of your clients and their own manner.

Do you have to identify a specific style? No, but you do need to identify your clients’ tastes and desires very clearly. No two people have exactly the same tastes, so any two people living in the same house are likely to see things differently – and it’s your job, not theirs, to find the right blend.

Determining tastes and desires can seem like psychoanalyzing your clients, but it’s well worth the exercise: Your final product will be better, your clients will be happier, and you’ll make more money because you planned well and get more referrals because they are so happy. All you need are some tools – and that’s what this article’s about.

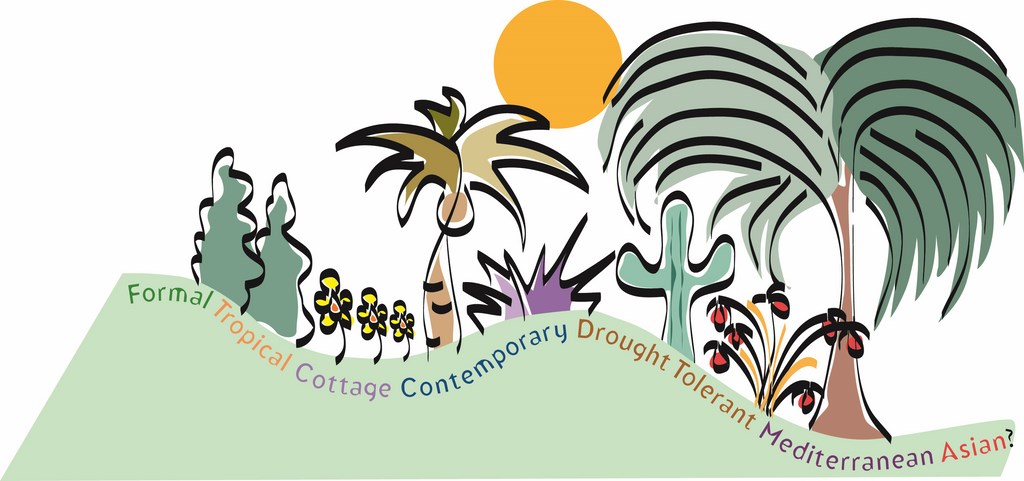

Let’s look at some general examples of the way people usually refer to landscape styles:

• Formal: If your clients say they want a formal garden, they may be leaning toward manicured hedges, large lawn areas and more structurally designed plantings. A good example of a formal style would be a boxwood hedge surrounding a rose garden.

• Tropical: Typically, when clients tell me they want a tropical look, they want palms and larger-leaf plants. Hibiscus and ferns are also popular tropical selections.

• Cottage: Also known as the “English Garden” look, this usually means lots of perennials, roses and flowering plants. Within this category, however, you need to determine whether your clients are thinking about a “wild” look, a more manicured look or something in between. In other words, saying “I want an English garden” doesn’t necessarily mean they want chaos.

• Contemporary: By contemporary, your clients might be telling you they want strong vertical lines using bamboo, horse’s tail or other “strappy leaf” plants including agapanthus, but there are other possibilities here. You need to ask more questions and get a better picture of what they’re thinking of when they say “contemporary” – and find out whether they’re after a sparse look featuring only a few varieties or want a fuller look.

• Drought Tolerant: Here’s another style where you should ask more questions to get a clear definition. To some, “drought-tolerant” means cacti and succulents; to others, it’s lavender and rosemary. What’s happening in the latter case is that these clients are using the terms drought-tolerant and Mediterranean interchangeably – and that’s something you need to sort out.

• Mediterranean: A Mediterranean look generally has an arid cast to it – one that often includes gray foliage or plants that look a little rangy or leggy, such as verbena. This style might also include use of lavender or rosemary.

• Asian: In landscape terms, Asian style can be many different things. Most of us think of maples, azaleas, camellias and deliberately placed plantings worked in with gravel paths or large areas of a single ground cover or planting. Often, this look has features designed to simulate mountains or other natural textures within a landscape.

For instance, gravel is sometimes used to simulate water in a dry river or waterway.

While it’s true that no two people like exactly the same things, it’s important to recognize that they may like elements of two or three or more of these categories and that it’s possible to mix styles if you know what you’re doing. It may take some digging to find out that what they really want is agapanthus around the edges of their formal garden, but this may be just the touch they’re after.

All seven of these styles are popular where I work in California, and I suspect you might add a few regional styles that feature favorite local species to the list. It’s also the case that your clients may refer to these style groups by some other name. As a result, it’s a good idea to ask some questions to narrow the range of possibilities and put yourself in a position of sounding like the expert even if you have no idea what style they are talking about.

STYLE AND DESIGN

In my last column (WaterShapes, June 1999, page 20), we determined that the size of the plant dictates space needs and that size may be determined by the style of the plant.

Existing plantings or other features may be your guide here. If the yard has established palms and philodendrons that the client wants to keep, you can work with and around them to create a “tropical paradise.” But keep in mind that you don’t need to be limited by these existing plantings or anything else as you design. Your clients, for instance, may want to mix roses or a perennial border in with the existing tropical look.

Can you do that? Absolutely – and if you’re uncertain about how to do it, find someone who can help you. There are no hard and fast rules about designing with different plants. You can mix anything – so long as you know how to do it!

Let’s say you have a mature tree in a very prominent location. The size and style of that tree may dictate a certain style for the rest of the landscape; it may even lead you to change the contours of the watershape. Say, for example, that your clients want a contemporary look and a rectangular pool – despite the fact there’s a mature sycamore or oak right in the middle of the yard. What do you do?

Short of convincing the clients to remove the tree, you might suggest a different geometric shape for the pool that still keeps its linear, contemporary flavor. You might also shift gears and suggest a style change, because the sycamore or oak would fit nicely in a cottage-style, Asian or formal yard. You might also mix styles, creating a new one that incorporates a number of different themes and ideas.

As you think things through and work with the clients, remember that different styles may also dictate different irrigation requirements. Let’s take drought-tolerant plants or succulents as an obvious example: They certainly need less water than would a perennial border.

This issue may be addressed simply by adjusting a sprinkler clock, but sometimes that’s not the case. What happens, for instance, when you put a regular irrigation system into an area in which the clients want only roses? Roses should be watered at the roots either by a flat spray, a soaker hose, a drip system or some other method that keeps the leaves dry. Drip systems require different installation than do regular sprinklers.

This may seem inconsequential, but poor planning will cost you time and money later as you struggle to adapt systems to plants. That can be particularly discouraging when it’s something you could easily have determined before the sprinkler system was installed! We’ll discuss the different irrigation needs of various plants in a future column; for now, it’s enough to say that planning is preferable to going back and changing all the sprinkler heads.

DETERMINING CLIENTS’ DESIRES

Assuming you have lots of resources at your disposal about plants, styles, irrigation and how they all go together, that still leaves you with the challenge of figuring out what your customers want. Here’s a list of questions to help you:

[ ] Do you have any pictures that show the styles of plantings you like? [ ] Do you have the addresses of any houses with planting styles you like? [ ] What types of plants appeal to you? Do you prefer tropical plants, roses, something else? [ ] Do you want to see things in your yard that you don’t see in anyone else’s yard – or would you prefer to have more common plants? [ ] Do you know the names of any plants you like? [ ] What colors do you like? Which ones don’t you like? (Many people hate orange; they don’t know what they’re missing!) [ ] Do you want a wild look, a natural look or a manicured look? [ ] Is there a dominant plant you would like to see everywhere in your landscape? [ ] Do you like symmetry, or is asymmetry your preference? [ ] What is the planting budget? (Uncommon plants typically cost more, so steer them in the right direction. This may in fact determine the style of planting they choose regardless of what they want.)If none of these questions (or not enough of them) can be answered to give you an understanding of what style they are looking to achieve, you may need other resources.

HITTING THE BOOKS

My favorite resource? The Sunset Western Garden Book (Sunset Publishing Corp., latest edition 1995). For information on plants, this book is basically the Bible of landscape designers and architects in the West. It’s probably the best resource for details on plants commonly available at wholesale nurseries. It’s also good for ideas, particularly if you use the sections on plants for specific situations (such as shade-tolerant, drought-tolerant or deer-resistant plantings). Better still, the folks at Sunset have recently released a national edition, so we’re all covered wherever we go.

While The Sunset Western Garden Book is definitely tops, there are several other publications I recommend:

• Taylor’s Master Guide to Gardening (Houghton-Mifflin Co., 1994): Organized by types of plants (including trees, annuals and perennials), this is a good overall guide with lots of pictures and plant descriptions.

• Taylor’s Guide to Garden Design (Houghton-Mifflin Co., 1988): This is a great resource to hand to your clients and ask them to tell you what they like and don’t like – and why. I use it frequently because of its great pictures and ideas.

• Taylor’s Master Guides (Houghton Mifflin Co., 1988): This is a whole series of books, each one on a separate topic from trees and shade plants to water plants, perennials and more. As with all the other Taylor guides, these give good descriptions of plants and feature lots of great photography.

• The American Garden Guides (Pantheon Books/Knopf Publishing Group, 1996): This series is similar to Taylor’s Master Guides, but it features different plants in many cases, so I recommend having both series on hand.

There are also several books I like that specialize in perennials and color gardens, including Best Borders by Tony Lord (Viking/Penguin, 1995), The Cutting Garden by Sarah Raven (Reader’s Digest, 1996) and Color Garden by Malcolm Hillier (Dorling Kindersley, 1995).

Another great way to determine your clients’ tastes (if books like these aren’t sufficient) is to take them to a nursery that stocks good-quality plants – and a good selection of those plants. Have them wander through the nursery and show you what they like – and what they don’t like. Remember: It’s just as important (and sometimes more important) to know what they don’t like.

If you go through all of this and are still truly stumped when it comes to deciphering your clients’ style, it’s time to consult a landscape professional – or e-mail me at [email protected].

Stephanie Rose wrote her Natural Companions column for WaterShapes for eight years and also served as editor of LandShapes magazine. She may be reached at [email protected].