Revealing Our Past

As someone who has spent years digging into the history of landscape and watershape design, it comes as something of a surprise to me that, alongside the luminaries who dominate discussions of the origins of familiar design approaches, motifs and styles, stands at least one practitioner who is not nearly as well known as he should be.

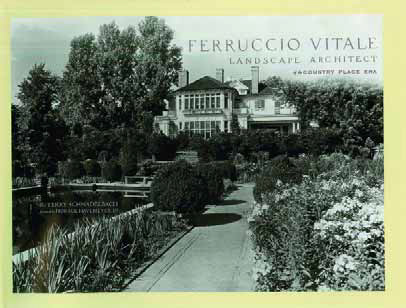

That man is the subject of Terry Schnadelbach’s Ferruccio Vitale: Landscape Architect of the Country Place Era (Princeton Architectural Press, 2001). I had never heard of Vitale, which, after reading this fascinating 320-page account of his life and work, truly startled me. I studied landscape architecture in college and have been an avid reader of books on wide range of design-oriented subjects ever since, and it actually bothers me that this is my first contact with such a great landscape artist.

As Schnadelbach explains, you need to delve deep to pull up Vitale’s name. He worked early in the 20th Century in the “second generation” of landscape architects who succeeded eminences including Frederick Law Olmstead. Indeed, Vitale first hung out his shingle while Olmstead was designing and overseeing installation of New York’s Central Park.

Through those years, the most prominent (and still celebrated) American designers pursued distinctly naturalistic designs in response to the formalism that defined European garden traditions. Vitale, by contrast, was an advocate of more structured forms and plied his trade mostly on Long Island (and then elsewhere) for an array of wealthy residential clients.

According to Schnadelbach, Vitale never sought publicity and tended to work in collaboration with architects who took the lion’s share of the attention and most of the credit. But he was no slouch, designing the gardens adjacent to the Washington Monument (one of his few public works) as well as the fountains at Longwood Gardens, where he collaborated with Pierre DuPont. It also bears mentioning that Vitale was one of the 11 founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Not only was he one of the first designers to focus substantially on residential work, but he also broke new ground by breaking down the barriers between designers and installers and, in doing so, defining that professional option for generations to come. He founded numerous firms and brought in constant streams of other designers as colleagues and partners.

Most amazing of all to me, Vitale was the one who originated the practice of digging up mature trees and wrapping their root balls in burlap – a means by which, he said, he could create “instant” gardens populated by mature trees and various other full-sized plant materials. Finally, and perhaps most significant to readers of this magazine, Vitale is credited as the very first landscape architect in America to incorporate swimming pools and tennis courts in his designs.

Unhappily, the vast majority of Vitale’s works (dated mostly to a span from 1910 to 1935) have been altered beyond recognition or simply no longer exist. Indeed, the pages of Schnadelbach’s thoroughly researched book stand as the primary record of his multiple achievements. He comes through as a bit of a renegade, with a body of work that reveals a restless, tirelessly creative spirit and engine of compelling design ideas.

In many respects, he was a man well ahead of his time and, as a source of inspiration, strikes me as being second to none. Here’s hoping this book helps elevate this remarkable man’s reputation and earns him his rightful place as a pioneer of landscape architecture and as one of our most cherished historical influences.

Mike Farley is a landscape architect with more than 20 years of experience and is currently a designer/project manager for Claffey Pools in Southlake, Texas. A graduate of Genesis 3’s Level I Design School, he holds a degree in landscape architecture from Texas Tech University and has worked as a watershaper in both California and Texas.