Questionable Accolades

Most people I know enjoy being recognized for a job well done. From a simple pat on the back to the Nobel Prize, we get a sense of affirmation when our best efforts are seen and appreciated.

Yes, there are those who see the work as its own reward. For most of us, however, recognition is a good thing, whether you prefer the warm-and-fuzzy side of being singled out for public praise or see the business advantage that comes along with recognition. Whether you’re a film star brandishing an Oscar or a swimming pool contractor with an armload of design awards, there’s an enhanced marketability that accrues to those with trophies on shelves and plaques on walls.

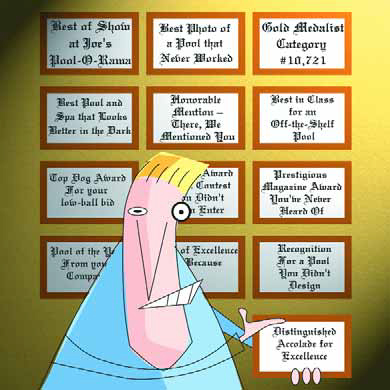

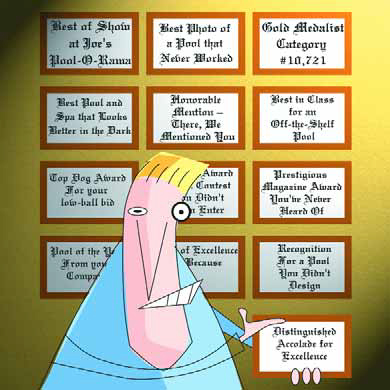

For years, the pool/spa industry has recognized the marketing function of recognition and has instituted numerous – and I do mean numerous – design-award programs. National association awards, regional or chapter awards, trade-magazine awards, trade-show awards: It’s a cavalcade of programs intended to honor performance across a broad spectrum of categories, and I must say that I myself have submitted many projects for consideration through the years.

Recently, however, I’ve developed serious reservations about the validity and relevancy of this plethora of design-awards programs and offer up the following as food for thought.

MORE, MORE, MORE

Before I detail my concerns, let me start by saying that there’s a good bit of sizzle that makes these programs tick.

By my count, there are now more than a dozen of these award venues in the United States alone, with literally hundreds of plaques and trophies being handed out each year. The ceremonies seem to be gaining in pomp and sophistication – nicer slide presentations, better settings, fancier dress and good times all around.

As one example, I recently attended the awards event staged by Region 3 of the Association of Pool & Spa Professionals (formerly the National Spa & Pool Institute). All was done with top-drawer aplomb, with most everyone dolled up in black-tie attire, several entries worthy of recognition, a beautifully decorated room and a dazzling audiovisual presentation.

In days gone by, I was a four-square supporter of these programs and have the hardware to prove it in the form of around 100 plaques. A handful of them adorn my office walls, but most are stashed away in a box in a closet. I derived the obvious marketing benefits from my participation and for most of my professional career was an advocate for the whole concept of using awards as a means of elevating the industry’s collective self-image.

Beyond the altruism, I also used my awards as they were intended: to impress my clients. Let’s face it, past clients love learning that their watershapes have been recognized for excellence, while prospective ones often cotton to the idea of having their projects installed by an award-winning firm. In a universe in which there are few ways to distinguish pool companies beyond price, peer recognition can indeed be a powerful marketing tool.

Given the upside, what on earth could make me see problems with this form of recognition? Well, when you step back and analyze the true nature of these programs, you begin to see cracks not only in the overall concept, but also in how they are administered. And these are misgivings that have been growing in my mind for years – especially spurred on by the fact that I now have the unusual distinction of having been given an award in a design competition I never even entered.

DOWN A NOTCH

First let’s consider the judging process and what’s actually being evaluated.

Each year amid some level of promotional fanfare, organizers announce the program to some targeted group – members of a given association or association chapter, for example, or readers of a specific magazine. There are typically lots of categories covering inground concrete pools of various sizes and/or shapes, commercial pools of varying functions, vinyl-liner and fiberglass pools, inground and portable spas, pool/spa combinations – the lists go on and on and seem to be in constant states of expansion.

The entry requirements typically involve payment of some kind of fee, a brief description of the project and, of course, photographs. Long before I or anyone else began offering critical views of awards programs, it was widely acknowledged that these programs are, to a large extent, photo contests.

There’s no question that firms paying top-notch photographers to shoot their work have the inside track on bringing home the gold. Because swimming pools (and most other bodies of still water) can be beautiful simply by virtue of their reflective surfaces, a good photographer can often make a fairly unimpressive design magical by capturing the reflection of a sunset, clouds or surrounding greenery. These professionals know how to manipulate exposures and work with filters and lenses and are smart enough to wet down rockwork and decks, artfully arrange furniture or plantings around the water and find the absolute best angle for the shot.

I know this is a factor because I’ve seen beautiful designs that suffered in judges’ eyes because they were represented by lackluster photos. There’s also the fact that the two dimensions of still photography cannot capture the essence of a watershape: the depth of the scene, the light dancing on the water, the sights and sounds of moving water. Given these limitations, winning a design competition can come down to something as simple as the time of day a body of water was photographed.

An even bigger problem with basing awards primarily on photographs is what they don’t show. A true “design award” should be based on the design in full, not just on aesthetic elements. How often have we heard of beautiful-seeming watershapes that are, in truth, technical nightmares? The photos don’t show the structural design or the plumbing, and none of the current design competitions has ever asked to see views of the equipment set.

With water-in-transit systems, for example, this lack of information on the hidden details is critical. Without properly sized or configured troughs, gutters, plumbing loops or surge tanks, these systems can experience catastrophic failures. No matter how good it might look, recognizing such a system without proof of the adequacy of its hydraulic design is, at the very least, problematic.

Should the awarding process require submission of plans, specifications, construction photos, or even involve on-site visits by judges? In a perfect world, the answers would all be yes, but I’m certain that organizers of existing programs would argue that such an elevated process would be unwieldy and expensive and would drastically reduce participation. I’d counter, however, that until such a rigorous program exists, we will never truly be recognizing the best we have to offer.

OFF THE SHELF

As mentioned above, another defining characteristic of most award programs is their phenomenal ability to invent new award categories.

I can see why they do it – basically because it multiplies their capacity to recognize members or subscribers – but I confess to having a problem with awards for things like the installation of portable spas, vinyl pools or prefabricated fiberglass pools. These products are designed, engineered and manufactured in a factory, and it seems rather absurd to give someone an award for simply placing one of these items on a redwood deck or in a smartly contoured hole in the ground.

|

Big and Brassy For anyone concerned about the legitimacy of awards competitions, here’s one guaranteed to fire you up. I’ve just heard about a large company that invented its own in-house design-award program. The entries were drawn entirely from the company’s own project log, and the contest organizers actually had the nerve to declare one of theirs to be “Pool of the Year.” More amazing yet, they’ve been promoting the fact that one of their projects was granted this prestigious award, making their own internal contest seem on par with the best of the national competitions. — B.V.B. |

I do think it would be wonderful if there were awards given to manufacturers for a particularly outstanding or innovative product – in the way, for example, Motor Trend recognizes top car models each year. Such a program does not currently exist in our industry, but I can’t help thinking it might have great value and could be a spur to product development, innovation and increased competition. That’s not a bad bunch of outcomes, but it’s a concept that isn’t likely to come to fruition anytime soon.

What happens instead in our industry is that a contractor who literally pulls a manufactured item off the shelf and puts it in place can walk away with the prize. It’s easy to understand why this happens: Trade associations and trade magazines (with the exception of WaterShapes, which has no awards program or any affiliation with one) are broadly based, and it would be a violation of the egalitarian spirits with which they operate to recognize the builders of custom-concrete watershapes while ignoring the work of others.

The fact remains, however, that this desire to be inclusive dilutes the significance of these programs and leads many designers and contractors to opt out because they want their projects to be recognized in a process that really means something to them, their peers and their clients.

(Speaking of clients, I’ve always thought that, in some form or other, the voices of those who pay for projects should be included in design-award submissions. After all, making the client happy is a huge point, and it’d be great if customer satisfaction could be part of the formula.)

The underlying point here is that the sheer number of awards and categories dilutes the impact of the programs. It would be more exciting to have truly national awards where one and only one recipient received an award and the number of categories was strictly limited rather than expansive. Think of an award given to the designer who created, for instance, the best inground concrete residential pool in all of the United States: That would be a prize with real meaning and prestige.

DUE CREDIT

The final problem I have with design awards is a big one, and it has to do with who enters in the first place.

For starters, there’s the simple fact that participation is generally limited to members of a given association or readers of particular trade publications. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, except for the fact that many of the finest projects are executed by people who are essentially out of the collective loop and feel no hunger for recognition of the sort provided by award programs.

At the same time, many of those who do enter really have no business doing so because they didn’t actually design the project. Fact is, design awards in the pool and spa industry are generally given to swimming pool contractors, and while I’m sure some of them do their own design work, it’s a known fact that a great many do not.

My friend and fellow Genesis 3 co-founder Skip Phillips often comments that the key to winning design awards all too often is a matter of being the low bidder on construction of someone else’s design.

Frankly, this is an outrageous state of affairs: To me, it is unconscionable to bestow design awards on those who do little more than build a vessel and circulation system. And in so many spaces, landscape architects or designers are involved and it’s the presence of the plantings, hardscape and overall arrangement of the space that really wins the admiration of uncritical judges.

In the awards programs run by associations in the fields of architecture or landscape architecture, it is entirely unacceptable (and perhaps even legally actionable) to claim credit for someone else’s design. In the pool/spa industry, however, a firm that does little more than put a low price on construction and hires subcontractors gets to take home a medal and use it to promote their “design capabilities” to unwitting clients.

The solution to this particular issue is simply to require contractors who enter awards programs to cite the designers if they themselves did not actually put pen to page to create the original plan. As it stands, however, this is not the way these programs operate.

It’s unreasonable to think that the industry is going to make a sea change in the way it hands out accolades. After all, these shortcomings are nothing new and for whatever reason the problems I’ve described don’t seem to bother too many people. Yet, I can’t help thinking that if our aim is truly to recognize excellence in design, then we should do more to ensure the process itself is worthy of a prize.

Brian Van Bower runs Aquatic Consultants, a design firm based in Miami, Fla., and is a co-founder of Genesis 3, A Design Group; dedicated to top-of-the-line performance in aquatic design and construction, this organization conducts schools for like-minded pool designers and builders. He can be reached at bvanbower@aol.com.