Practicing Nature’s Balance

It all begins with the water.

The first thing anyone approaching the world of ponds needs to understand is that life-supporting water is quite unlike the sterile water found in swimming pools or spas or many other watershapes. A second and related point is that clear water is not necessarily healthy water when it comes to the needs of the inhabitants of the pond.

For a pond to be healthy, its water must meet the chemical requirements of plants and fish by having an abundance of some things (such as nutrients) and a near-total lack of other things (such as pollutants). Sanitized water may be beautifully clear, but the fact that sterile systems are designed to knock out nutrients and work chemically because they are “polluted” with chlorine and algaecides makes them completely unsuitable as life-supporting ecosystems.

The goal with ponds is to work with nature in balancing the life-sustaining features of the water – and to set things up in such a way that maintaining that balance will be something your clients can do long after you’ve moved along to another project.

To do so, you need to embrace the water-quality basics outlined in the last issue of WaterShapes (click here). You also need to know how to select a liner, size the equipment properly, install everything in good order and teach your clients what they need to know to meet their desire for a pond that functions well, looks nice and fulfills their quest for a source of relaxation, enjoyment and entertainment.

SHAPES AND SIZES

Let’s start by looking at the range of living water systems sold in today’s watergardening marketplace. Just as is the case with pools and spas, these ponds come in many sizes and shapes and from many sources, with size probably being the most important factor because it tells you what you need to know about liner and equipment selection and how much life a given body of water can reliably support.

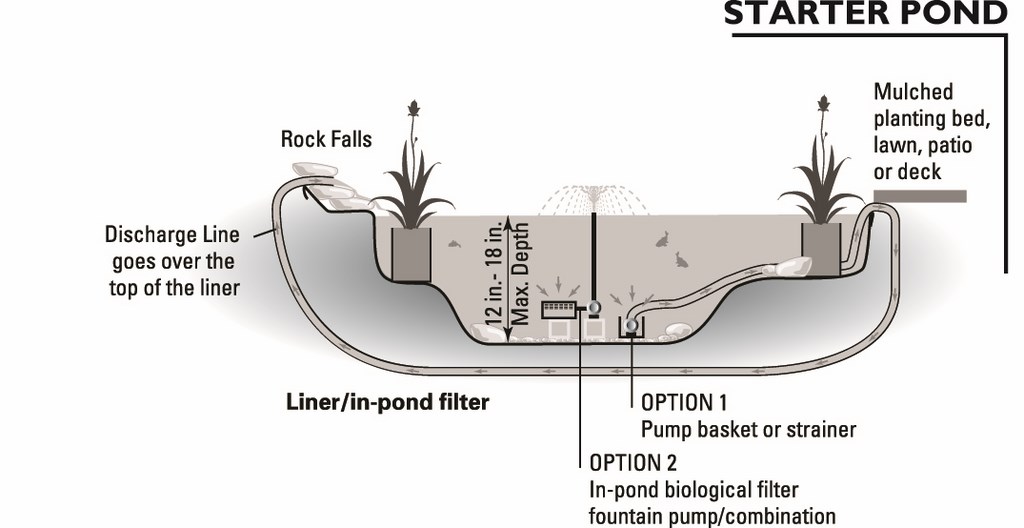

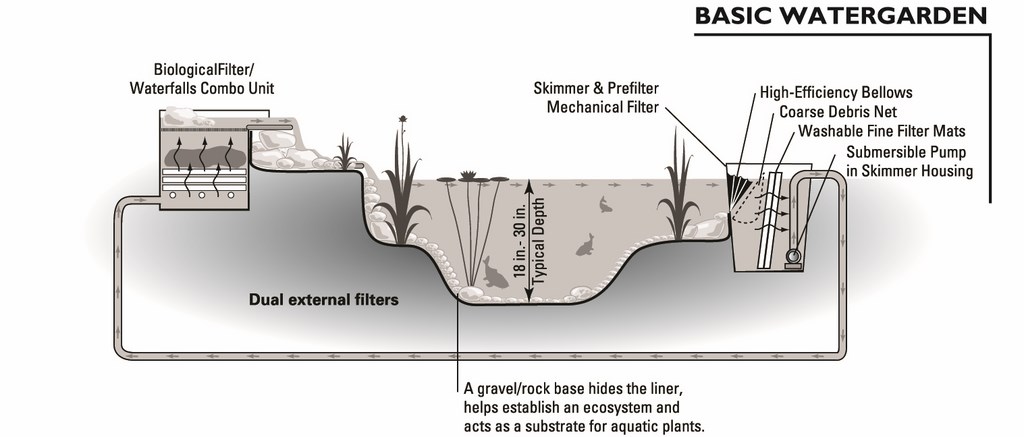

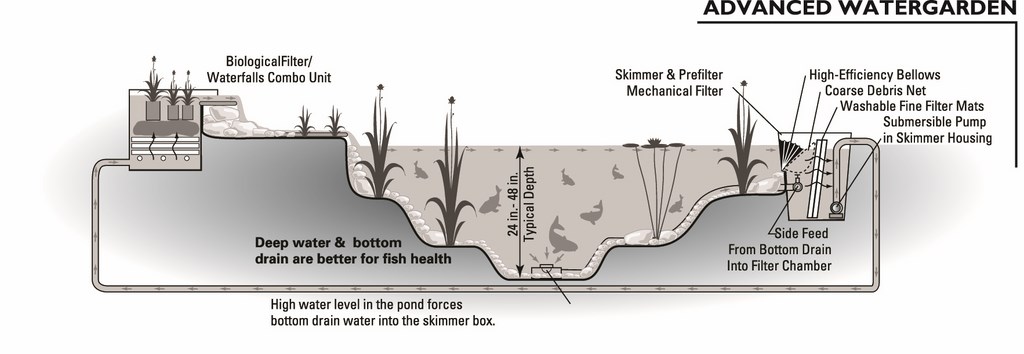

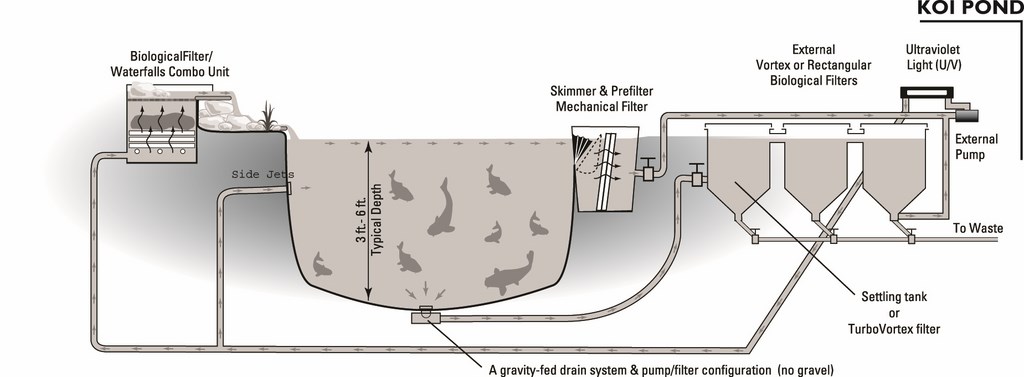

| These cross-sections give a general idea of the dimensional distinctions among ponds, starting with the small ‘starter ponds’ at the top and moving down to the large ‘koi ponds’ at the bottom. As a rule, the bigger a pond gets, the easier it is to maintain – and the more stable is its ecosystem. |

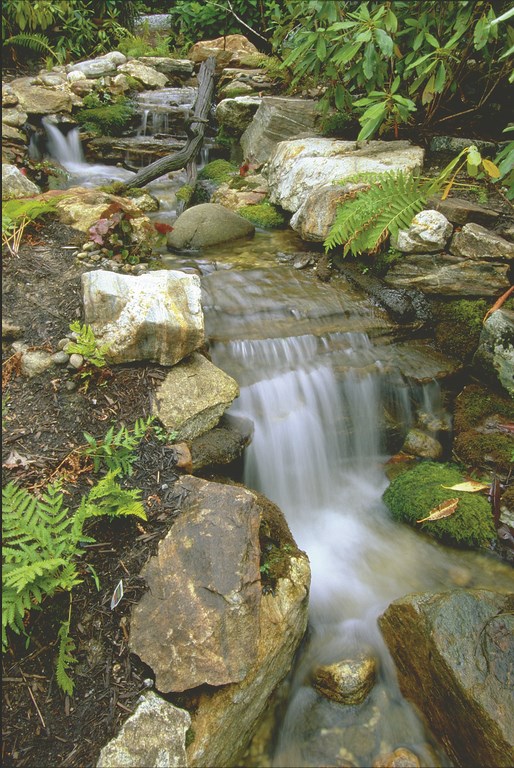

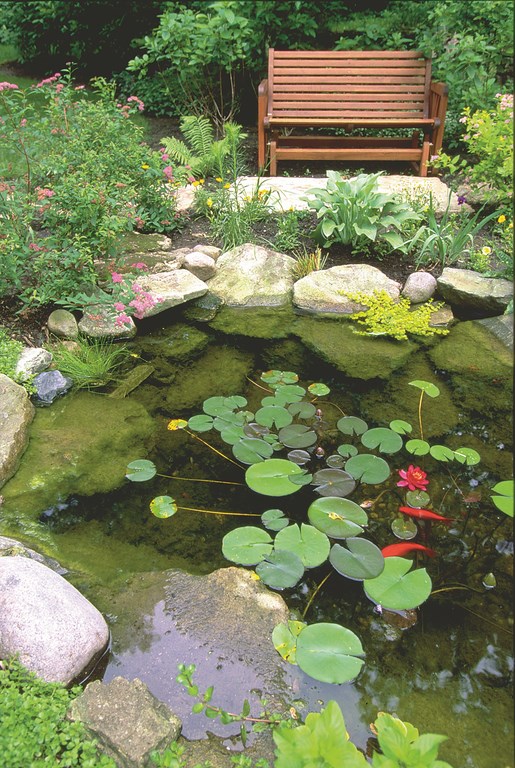

| Small starter ponds may be a maintenance challenge, but that doesn’t mean they lack aesthetic appeal, as can be seen here. (Photos by Gary Wittstock, courtesy Pond Supplies of America, Yorkville, Ill.) |

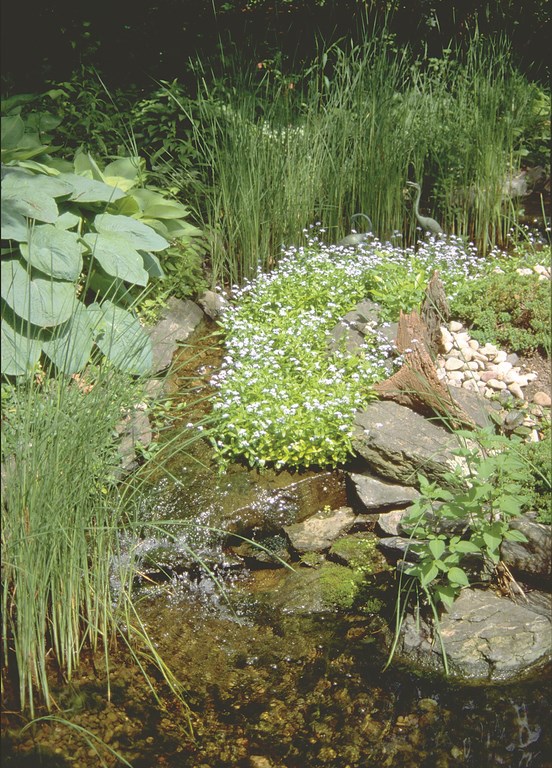

| Advanced watergardens give the installer and homeowner a chance to let their imaginations get fully involved in the design process to produce spectacular results. |

As a rule, ponds at all levels should be built as large as possible, basically because larger ponds are less costly per gallon, require much less maintenance and are, most important, more stable ecologically for fish and plants. At our company, we encourage new pond clients to “build their second pond first” and to avoid starter ponds. We do so because the biggest complaint from first-time pond owners is that they wish they had gone with something bigger and easier to maintain.

Absolutely, clients who opt for starter ponds can experience success, but in the long run, they’re going to get more enjoyment and increased success from a larger pond. The moral of the story for the designer is to think in terms of upsizing the pond whenever possible!

PROPER CONTAINERS

Whatever the size or type, the main thing a pond needs at the most practical level is some means of permanently containing its water.

Most of the time, flexible EPDM rubber liners are used in building watergardens. Unlike pool liners, these sheets are not embedded with any anti-mildew or bactericidal chemicals. Those chemicals inhibit the beneficial growth of the microbial portion of the ecosystem and may even kill the fish.

|

Care and Feeding When it comes to ponds, maintenance depends on size, type and location. Starter ponds are a challenge in this area. They’re harder to keep in balance because of their smaller water volumes. There’s also the fact that the filter is in the pond bottom, which means that the owner faces the unpleasant task of pulling it out for cleaning – sometimes daily, if not more often. Larger watergardens are filtered with a skimmer and a biological filter, so they stay cleaner. If such a pond is set up right, maintenance should take no more than ten minutes or so each week (except when starting up the pond in the spring or shutting it down for winter). As a rule, the bigger the pond, the less time the owner will spend maintaining it. And the light maintenance burden there is with larger ponds can be reduced even more by using larger or multiple skimmers – an option not generally pursuable with starter ponds. Any pond also requires some pre-maintenance. Once the pond is full, the owner must know that any municipal water must be de-chlorinated before it will be safe for fish. (Well water is generally fine without treatment, but it’s always a good idea to have it tested for fish-harming pollutants before fish are added.) Beyond that, a natural ecosystem requires very little by way of chemical treatments, although flocculants are sometimes used to clump algae cells or dirt after a heavy rain and products designed specifically to keep down long strands of algae are sometimes needed, especially through the pond’s first year or two. Then there the bacteria cultures and enzymes that must be added to jump-start the pond’s ecosystem and avoid green water. Once the ecosystem is up and running, however, all that’s usually required is addition of fresh bacteria once or twice a month to help keep the pond clean and safer for its fish. As for seasonal maintenance, even in the freezing climates found in the northern United States and Canada, fish and plants are best left outdoors to hibernate naturally. A two-foot-deep pond with a surface aerator or heater to keep a hole open is sufficient for most ponds up to Planting Zone 4. Just clear the water of debris before the first freeze hits so debris won’t sit on the bottom. Finally, in colder climates and with larger fish, deeper is better as the warmest water (around 40 degrees F) forms a “warm puddle” on the pond bottom. Do not disturb that bottom layer of warm water with pumps, and remember to turn off any bottom drains! — J.R. |

Pre-formed pond liners also are available and come in a variety of sizes, depths and contours for shelves. The pre-fabricated shelves allow for some choices in placement of plant material and habitats, but flexible liners are less expensive than their pre-formed cousins and place no limits on the designer. In fact, the process of digging the hole for a flexible liner pond is much more free form in a watergarden than it is with any swimming pool.

The main variable here is depth. Typical starter and pre-formed ponds range in depth from 18 to 24 inches, while advanced watergardens reach down three or four feet and koi ponds can reach depths of six feet or more. As a general principle, the deeper the water and the greater the volume, the better the pond will be for fish.

Greater depths, however, might raise building-code questions, so as an installer you need to check local agencies for depth allowances and any fencing requirements. (For their part, however, small ponds tend to fit into a landscaping category that does not require permits or fences.)

And because small ponds tend to be shallower, they are also safer, easier to clean and friendlier to plants that need sunlight at a level you just don’t get with projects of koi-pond depth and configuration. By the same token, very shallow ponds (with depths of 12 inches or less) tend to foster undesirably high levels of algae growth.

MECHANICAL FILTRATION

Once the pond container is selected, it’s time to focus on filtration. Just as with swimming pool or spas, you must install a system that effectively removes larger dirt and debris – and the basic selection principles are accordingly similar.

As with a pool, the first stage of pond filtration involves collecting as much debris as possible before it has the opportunity to sink to the bottom, so skimmers are a must. The second stage of filtration is designed to remove small particulate matter via some sort of filtration medium. In a pool, a third stage calls for adding chemicals to keep the water clear. In a pond, by contrast, the third stage has to do with adding bacteria and enzymes to remove invisible pollutants such as ammonia.

The point of the first-stage, mechanical filtration in a pond is to prevent the debris from breaking down into smaller components. The more debris that is left in a pond (especially through the winter), the more likely that fish will have health problems. This is so because organic material such as leaves and grass clippings release a variety of chemicals into the water as they decay. They also provide shelter and nutrients for fish parasites. Not only will this chemical soup harm fish, but it will also promote green algae growth or turn the water brown.

In a natural ecosystem, these decay compounds would be part of the total system, but the goal in man-made ecosystems is to control the growth of some of the organisms in the ecosystem. In a lake or natural pond, green algae and fish parasites are fine, but that’s just not the case in a backyard watergarden. As is true with pools, bigger filters last longer between cleanings and handle larger loads – but it is possible to go overboard, so you should always check the manufacturer’s recommendations.

| The mechanical filter on this pond is well hidden in the rocks and does an efficient job of removing floating debris before it has a chance to sink and decompose on the bottom of the pond. |

Skimmers are rated in terms of the pond’s surface area, while biological filters are rated by its volume. Some units are designed for installation inside the pond, but using external models keeps your options open: If a bigger filter is needed, change-outs are easier and you don’t end up using more of the pond’s valuable interior space. Maintenance of external filters is also easier to manage – and it’s easy to hide them in the landscaping as well.

Mechanical filters need cleaning when debris slows the flow of water to the pump. Helpfully, most pond filters have large debris nets that act as prefilters – similar to the skimmer baskets in pool systems, only larger. It only takes about five minutes to empty the pond filter’s net and clean the mats, so it’s not a very time-consuming job for the homeowner.

High-pressure sand filters used very effectively in pools clog almost immediately in ponds because of the larger burden of organic material in a pond. The tanks can be used in pond filtration, but only if the filter medium is replaced with larger material that offers much larger pore spaces.

Most mechanical filters used on ponds also serve another purpose: Although they aren’t designed specifically for biological filtration, they do trap some smaller particles. As a result, they require backwashing on a weekly basis.

BIOLOGICAL FILTRATION

As was just mentioned, the water-cleaning action of a pond system’s mechanical filters is supplemented by a process of biological filtration in which bacteria, fungi and other tiny creatures break down all of the big stuff that comes their way.

In a pond, these bacteria must be on hand to consume the waste products of the fish before those compounds build up to toxic levels. Bacteria also seem to have a limiting effect on the growth of algae. Although there’s some controversy about how they do it, there is no question that the addition of a variety of bacteria cultures and their enzymes serve to reduce algae populations to manageable levels.

Keeping these bacteria alive is therefore an important part of keeping the entire ecosystem running smoothly. As a result, biological filters should not be cleaned, except when they are so blocked that water flow is diminished. (Bacteria have short lives, so they need a constant source of nutrients being washed over them – a flow that cleaning interrupts.)

In the design of a pond, there must be consideration of how and where these biological filters will be placed. They are designed to serve as hosts to colonies of microorganisms – and the more the better, so increasing the filter material size or the gravel surface area within the pond will promote more bacteria and be more beneficial to both fish and plants.

| Biological filtration in this pond is aided by extensive use of aquatic plants. These plants harbor bacteria that break down decomposing debris and help keep the water clean. |

Some filter boxes are large and hard to hide, but others can be buried in the ground and a few even have waterfalls built in, so the box can serve a double purpose. In our own designs, we often find ourselves building up any excavated soil into a pond-backing berm behind which we hide the filters. We also use the elevation change to create waterfalls and streams that flow toward the house.

This maintaining of the biological filter is one of the main differences between ponds and pools or spas. Healthy ponds and fish are completely dependent on good bacteria doing their job, and the biological filter box and circulation system must be designed to ensure a continuous, 24-hour-a-day flow of oxygenated, nutrient-laden water to support as large a population of bacteria as can be sustained.

Although it is possible to go for months without adding fresh bacteria into the system, it is a good idea to add some to both pond and filter on a regular basis when the water temperature rises above 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

THE HEART OF THE SYSTEM

Keeping the water moving in a pond of any size or description means you need a pump as a system component.

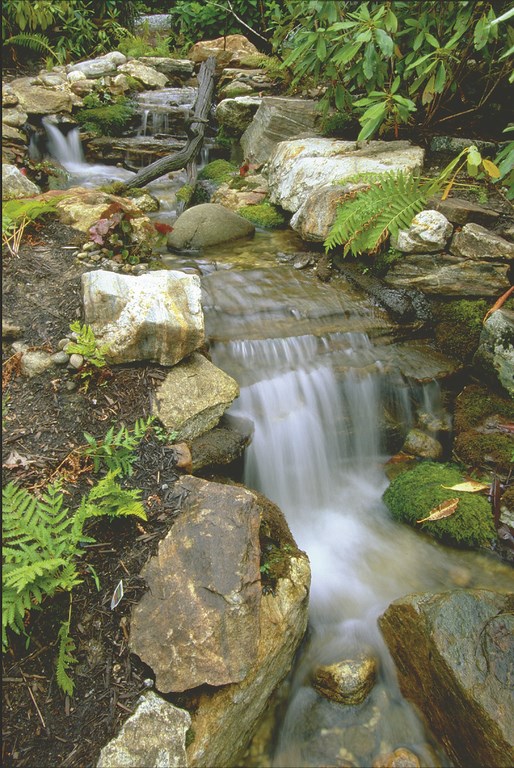

Pumps pull the water through filters and return it to fountains, waterfalls and streams – and the more splashing the better: It sounds and looks wonderful to your clients, and it also attracts birds like no other garden feature, which is why many homeowners are interested in installing ponds in the first place.

|

Struggling for Air Many people are aware that plants produce oxygen during photosynthesis, but few recognize the fact that plants also consume oxygen 24 hours a day through the process of respiration. So at night when there’s no sun and no photosynthesis, the plants and algae may actually remove so much oxygen from the water that the fish can be seen at the surface, gasping for air. This is a bigger problem when the algae that creates green water so overwhelms the pond volume that oxygen is depleted in just a few minutes after sunset. This algae needs to be controlled, and quickly, before other organisms die and eventually the algae dies, too, absolutely flooding the filter system with nutrients. At that point, even the bacteria in a biological filter suffer as well from a lack of oxygen. This is why pond systems need a skimmer to pull in oxygenated surface water. This is why also bottom drains are a good idea, because they circulate oxygen-depleted water from the bottom of the pond and give it a much-needed breather! — J. R. |

To accommodate the biological filter’s need for constant flow, most watergarden ponds are built with continuous-duty submersible pumps. These are installed most often in the rear chamber of a skimmer, where they silently pull debris across the water and out of the pond.

Some larger watergardens and most koi ponds have external pumps that are gravity-fed from the skimmer, flow through the filters and return the water to the pond directly or via a waterfall or stream. Here, having all of the pumps and pipes buried in the ground is important to achieving a natural look.

No matter where or how you install either style of pump, the device must run continuously for optimum performance of both the skimmer (otherwise, debris gets a chance to sink) and the biological filter (to sustain the bacteria). And if the pond has a waterfall, stream or aerating fountain, it also should run continuously to keep the water oxygenated.

This oxygenation via a stream, fountain or waterfall is important to a healthy ecosystem and is therefore an important design consideration. The water effects that pumps create (and that people and birds love) make up for the fact that there’s not much dissolved oxygen in the water available for fish – and that the situation gets worse in warm weather, with oxygen levels dropping as low as a fish-stressing two or three parts per million.

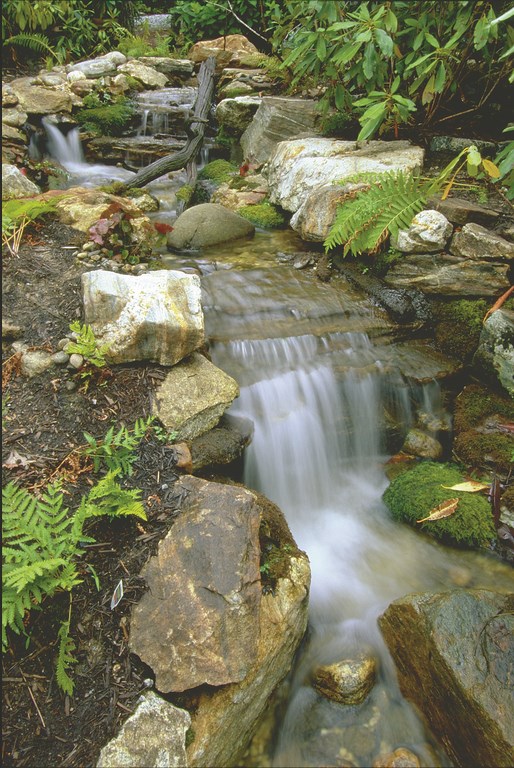

| Waterfalls can play a major role in keeping a pond’s ecosystem in balance. The aeration they impart to the water helps to keep the oxygen level up, and the agitation they lend to the system helps keep water circulating in all areas of the pond. |

The splash and movement any water effect provides at the pond’s surface helps life-sustaining oxygen and other gases to move in and out of the water – the perfect intersection of aesthetics and necessity.

In fact, the entire pond-design process might start and end with aesthetics, but at some point, basic animal needs must be accommodated. Fish (and other animals) are a critical part of the total ecosystem, and their waste in turn becomes the life-sustaining food for microorganisms. They also eat mosquito larvae and other pesky insects – and some even eat algae.

CREATURE COMFORTS

Without a doubt, fish add color, character and personality to any pond – and a real and true sense that the watershape has always belonged where it has been placed.

Caring for most varieties of fish is easy, and they can even be trained to eat out of your hand. The only thing to remember is that it’s easy to go too far and that you need to be careful not to add too many or let them outgrow the size of the pond or the filter system. Fish grow, but filters don’t!

Typical watergardens with mechanical and biological filters can usually support one five-inch fish for every five square feet of surface area. In other words, a ten-by-ten-foot pond (100 square feet of surface area) should support about 20 five-inch fish with some room for fish growth. (Because they usually have extensive additional filtration, koi ponds can usually be stocked with more and larger fish.)

|

The Algae Truth Any substantial algae bloom will require a pond owner’s special attention, but the accent should always be on prevention and control. Algae is best held at bay by having fewer fish in the water and by feeding them less, meaning fewer nutrients will be available for the algae. It also helps to have more plants in the pond to compete with the algae for sunlight and nutrients. One can also use chemicals, but only at the risk of throwing the ecosystem seriously out of balance. The best approach is a competitive planting strategy in which plants that grow better than algae are introduced. By adding more plants from each category of the submersible and shoreline varieties, more diversity is introduced and a healthier ecosystem develops – one with little room for algae. Good pond filters and routine pond care also help to keep algae in control. But Mother Nature will not allow nutrients to go unused, so if the pond does not have enough plants, she will add algae. Complicating the picture is the fact that some levels and types of algae are desirable. String algae, for example, can be a pestilence in a newer pond, but it is a tireless pond worker in the long run, helping to keep the pond water clear of single-celled algae and feeding the fish. In fact, it’s an important part of any thriving pond system. If algae does take hold and reach a point where the system can’t handle the burden any longer, much of it can be netted out or removed by hand, and there are mild calcium-binding additives that suppress the growth of string algae. The goal here is to control, not eliminate. A pond ecosystem may take as long as two years before the plants become large and plentiful enough to control string algae naturally, so urge your clients to patience and wait as the system move naturally toward balance. — J.R. |

Frogs, toads, dragonflies and other animals also will find their way to a watergarden for a few weeks at a time during the year. Turtles may be added to the mix, but they usually don’t stick around – and when they do, they have a regrettable tendency to feed on the fish, the plants or both.

Plants are important to the overall impression made by the pond as well, and many varieties will thrive in a well-designed system. These include mainly submersible plants, which live underwater and consume nutrients in competition with algae; and shoreline plants, which live with submerged roots with the rest of the plant out of the water. (Some shoreline plants are even tolerant of drying out a bit.)

Some plants, including the water lily and the lotus, have roots that grow deep in the muddy bottom of natural ponds – and they do just as well in the gravel of man-made watergardens. Their leaves and flowers float on or rise above the surface, while floating plants such as the water hyacinth trap air in their leaves and stems for buoyancy as their long roots hang down into the water to absorb nutrients.

As in the rest of the landscape, some watergarden plants are perennials and some are annuals that die with the onset of cold weather. There are numerous colors of flowers and leaves available for any aquatic gardener to be able to have blooms all season long. These plants also tend to require little maintenance – and they can’t be overwatered, as is unfortunately true of many of their land-locked cousins.

Of course, not all plants in the backyard ecosystem are desirable – algae being one. Just as an empty dry-land flowerbed provides the proper growing conditions for weeds by supplying sunlight, nutrients and water, an untended water garden will soon be overrun with the aquatic “weed” known as algae.

There are thousands of varieties of these single-celled organisms that will float in the water and eventually turn it green. Some algae grow on surfaces, while others grow as long, hair-like strands. And they grow best when they have plenty of nutrients and little competition from other plants. (For more on combating this nuisance, see the sidebar above.)

ON THE BOTTOM

The final touch in proper pond design is all about the hard stuff: rocks and gravel.

As insignificant as they might be out of water, small rocks and gravel are incredibly important in a pond. They provide an easy medium for plant growth and the spread of healthy, nutrition-gathering root systems. They also serve as a huge surface area for colonization by bacteria – a true, natural filter, especially when planted with aquatic plants.

| The rocks and gravel used at this stream’s edge help the biological filtration process as water flows down with stream. |

Beyond the ecosystem benefits, rocks and gravel are cheap and cost-effective. The cost-effectiveness comes in the fact that gravel cuts down the size (and cost) required of pond filters and pumps.

All it takes is a single layer of one- to three-inch stones to act as a great pond filter. Any thickness greater than that, and you run the risk of building up too many nutrients that will rob the system of oxygen and produce anaerobic conditions. (Note also that gravel and rocks are usually avoided in deeper koi ponds because they can interfere with the flow of water into their bottom drains.)

| In a system where everything is properly balanced, the gravel at the bottom will not accumulate large amounts of debris: The skimmer will have taken care of much of that burden before anything could reach the gravel, and bacteria colonies will take care of much of the rest of the dirt. |

Some builders of smaller ponds leave gravel out of their systems, usually because they see it as a negative when it comes to maintenance. That may be true, but the result is a need for larger biological filters to replace the surface area lost without the gravel – and a need to deal more directly with the layer of un-decomposed sludge that will collect on the bottom when there’s no bacteria there to break the organic matter down into solution.

| Appropriate use of rocks and gravel can dog-proof the edges of a pond’s liner – and give any human visitor something to hang onto in the event of a watery mishap. |

After adding shoreline plants, a few large stones lend a natural touch to the transition from wet to dry spaces. Large stones on the pond’s vertical walls also protect the liner from the claws of animals that get into the water and need a way out – and they give people unfortunate enough to tumble into the water something substantial to hold onto as they climb back to dry land.

STRIKING A BALANCE

As you weigh all of these design considerations – pond size, liner selection, gravel, equipment choices and the biological population you’ll introduce once the system’s up and running – it’s important to remember that all of these elements must work together.

In ways that just aren’t true with pools or spas or fountains, the features that make up living systems are wholly interdependent, and all factors go into creating balances that support the sustained presence of healthy plants and fish.

You and your clients can spend lifetimes learning more about the nuances of living aquatic systems, but it’s certainly possible to jump in and get your feet wet without years of experience. All it takes is a specific awareness of the needs of the creatures you’ll be introducing to your ecosystems, and a certain level of understanding of the balancing act you’ve initiated.

Just get the basics down: The rest is unendingly interesting and enjoyable.

Jeff Rugg, ASLA, is a writer, educator and consultant on landscaping and water gardening and an employee of Yorkville, Ill.-based Pond Supplies of America. He holds degrees in science, zoology, horticulture and landscape architecture and uses his many interests to help others learn about nature. Before joining Pond Supplies of America, he managed garden centers in Texas and Illinois and once owned his own water-garden and wild-bird store. His weekly newspaper column, “A Greener View,” is syndicated nationally in as many as 400 newspapers, and his articles and photographs have appeared in Pond Keeper, Water Garden, Landscape Contractor, Ponds USA, American Nurseryman and other publications.