Organic Artistry

Helena Arahuete joined the staff of John Lautner’s architectural firm in the early 1960s, at a point where he was turning out some of his most spectacular work. Indeed, Lautner can indisputably be said to have designed some of the most beautiful and unusual homes built in the second half of the 20th Century.

An apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright’s who studied with the master at Taliesen, Lautner was an exponent of the philosophy and discipline known as “Organic Architecture,” an approach Arahuete, now an eminent architect in her own right, has continued to use and refine while running the firm that still bears Lautner’s name.

She is now one of the world’s leading practitioners of Wright’s and Lautner’s approach to creating unique structures that are intricately and intimately tied to their surroundings. She is also so firm a proponent of the integration of watershapes into those architectural forms that in April 2000, she carried her message to the first Genesis 3 Level II Design School, held in Islamorada, Fla. – and welcomed an opportunity to present some of Lautner’s work here by way of defining the place watershapers have at the design table with the world’s great architects.

John Lautner always said, “Use nature as a source.”

That was his starting point. His designs were then inspired by the sites on which he worked, so each is unique and cannot fit anywhere else. That’s part of what organic architecture is all about: designing structures uniquely suited to their surroundings. It’s the far opposite extreme from a one-size-fits-all mentality.

And just as much of the individuality comes from clients as it does from the sites: In each case, Lautner interviewed them, uncovered their personal likes and dislikes and took all of this into account during all phases of the project. I do the same, and find it to be inspiring because every person is different, with different sensitivities, and you find endless sources of creativity and ideas by talking to them.

| Roots

The philosophy that drove the work of architect John Lautner, called organic architecture, is the philosophy of Frank Lloyd Wright and other great modern architects who have followed in Wright’s footsteps. Organic architecture is not an easy thing to summarize, because it means different things to different people. My own interpretation is that it is an expression of what happens in nature, where everything that’s living is designed for a purpose. Animals, for example, have skeletons, skin and coloration; they are beautiful and they make sense. The same is true of other natural forms, such as trees or even geological features such as rock outcropping and rivers. They also have specific forms that serve a purpose and make sense. In our architecture, we strive for forms that similarly serve purposes and make sense and revel in the fact that the ideas never get stale or become commonplace. Styles and trends will come and go, but philosophy endures. You can’t say you’ve seen a “Victorian” mountain or a “Chippendale” tree: Their designs and purposes are timeless and enduring in their beauty and purpose. They are beautiful because of the way they are. In that sense, organic architecture is a genre that transcends genre. That’s the ambition of great architects including Wright and Lautner – and can apply just as surely to the work of watershape designers and builders. – H.A. |

In the process, you’ll find some people who are more comfortable with elegant designs and lightweight, angular, cantilevered shapes. Or you’ll find clients who are interested in curved, sheltering spaces. In time, what you learn is that what might work for one client might not work so well for somebody else – and learn to celebrate the differences rather than perceive them as obstacles to be overcome.

These clues you get from your clients direct you to do things that are totally individualized. It forces you not to copy, not even from yourself, and to do things that are totally fresh. Just as each client is one of a kind, so is each site with its unique setting and views.

USING VIEWS

One of the primary things the site gives you is the view.

This was always a major factor in John Lautner’s work, and it’s certainly something I consider in my own. We take the best the site has to offer in terms of views, be they distant views or nearby, then we choose the areas we want to be seen from inside the home – and also select what should not be seen.

If you frame the view a certain way, it becomes a work of art – but a work of art that is never the same and constantly changes with the light of day, the seasons, the clouds, the position of the sun and light filtering through trees or casting shadows over ground and rocks. Within each site itself there is constant variety.

When you consider the view from inside the house, even a relatively ordinary view can be made to be far more interesting – and can benefit from appropriate placement of a watershape, for example. The key for the architect is to approach the design of the home or the space from the inside out. And I believe that this approach will work as well for watershapers who take an interest in orchestrating views and lines of sight.

This is something I constantly try to explain in lectures and classes, this idea that architecture is taken from the space surrounding a person who stands within a space and is something that develops outward.

This is something I constantly try to explain in lectures and classes, this idea that architecture is taken from the space surrounding a person who stands within a space and is something that develops outward.

In fact, this special perspective is what architecture is about and what separates it from other art forms. With a painting, for example, you stand in front of it and view the image in two dimensions. Sculpture offers a third dimension: You can walk around it, but you are still outside the work. In all forms of architecture, be they interior or exterior, you are inside the work, inside the sculpture.

To form a space around someone, you need to be aware of the experience that someone will have while inside this environment. To be effective in creating spaces for people to enjoy, you need to be aware of things such as scale and the relationship between differently shaped spaces.

If, for example, you move through a corridor with a low ceiling, this makes you feel a certain way. Then if you move from that corridor into a much larger space, the way you feel is transformed. You will physically feel the space and how it is affecting you in a certain way.

| Inspiration and Influence

John Lautner had a tremendous amount of respect and admiration for Frank Lloyd Wright and apprenticed under him in the 1930s at Taliesen, one of the great incubators for 20th-century architects and designers. While there, Lautner learned by doing, but he possessed sufficient vision on his own to understand the concepts behind the Wright philosophy and apply them in new and personal ways. Lots of people who apprenticed with Wright ended up following the shapes and contours of his designs – ornamental but deprived of spirit. Not Lautner: He took on the philosophy and Wright’s influence and found that with it, you could create totally original projects each and every time. In working with him and since his death, I try to do the same. You are unique, your influences are unique, the site is always unique and so is the client. The combination of these four factors is what leads to original forms of expression in processes that apply across all creative fields – including the design of watershapes. – H.A. |

If you are able to capture that influence in the way you shape an environment, I believe you’ve really achieved something.

PERFECT COMPANIONS

This designing from the inside out – that is, from the perspective of the person in the space – encourages the designer to use natural forms and complementary forms inspired by nature to create the experience of the person inside the environment.

In this respect, water is a very important element in design.

I’ve designed a project, scheduled to break ground soon, that has a long body of water with long benches right behind it. The idea here is simple: We want people to be able to sit next to the swimming pool while experiencing a spectacular view off into the distance.

By creating a place for someone to sit next to the pool with an unobstructed line of sight to the distant view, we are able in a very simple and straightforward way to bring the immediacy of the water together with the vista. In other projects, we’ve used structures with pools adjacent to sloped areas to block the view of objects at lower sight lines while framing the distant view along the far edge of the water.

There are countless other ways to integrate water into architectural programs, and Lautner used many of them in his long career. Using the photographs on these pages, let’s consider the use of water in three of Lautner’s projects. I’ll also offer some insights into his philosophical roots. Perhaps most important, I’ll offer my own perspective on a role for the watershaping consultant in the future of architectural design.

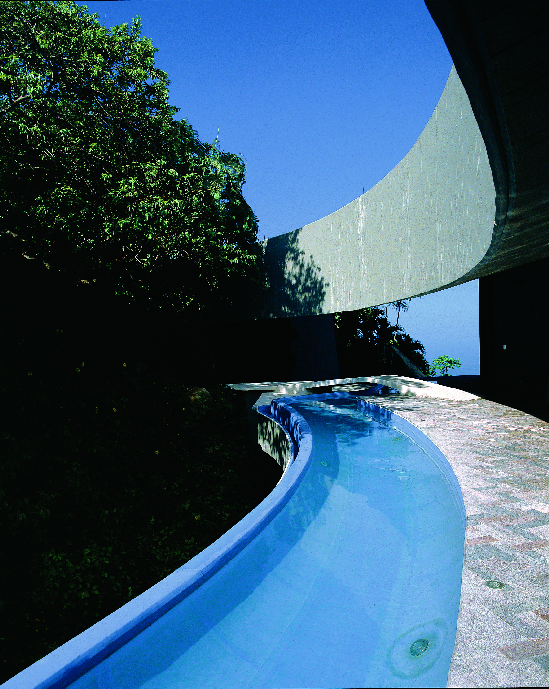

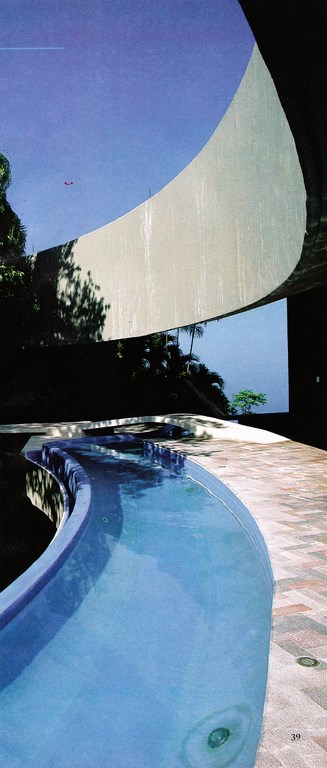

The Arango House (1969)

In the design of unlimited space, you have the opportunity to continue the inside to the outside and vice versa. The Arango House is an example of what can be done when the horizon is literally the limit – and of how the water plays an important role in creating and capturing this experience.

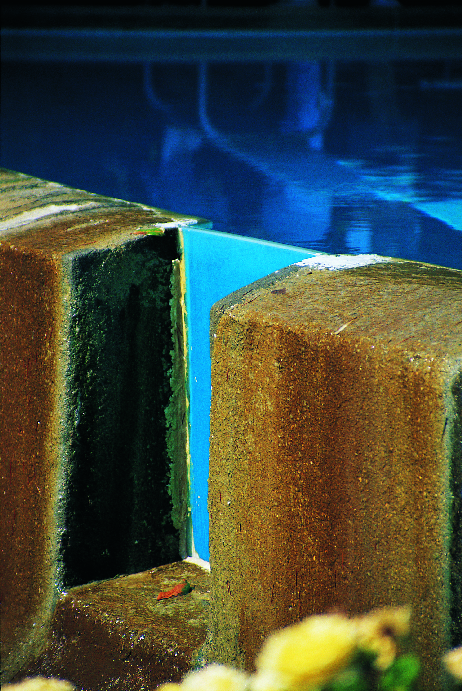

The site offers a beautiful view of the Acapulco Bay; and Mr. Lautner wanted to find a natural way to integrate the home’s exterior with this fantastic view. The moat, a truly unique feature at that time, wraps all the way around the home’s second floor with a vanishing edge overflowing into a gutter. All you see at deck level is the water disappearing into the water of the bay beyond.

At the same time, the moat is a safety device. Rather than having a railing, which would have disrupted the view rather than connect the home to it, you have this expanse of water that prevents people from falling off the cantilevered deck while still bringing the outside and the inside together. The pool is six feet wide and four-and-a-half feet deep, and the effect is breathtaking. You can literally swim around the house.

We had another client who had visited the Arango house and wanted the same thing for his house in Malibu, Calif. We didn’t like the thought of repeating a design we’d done in the past, but we consented to do so given the oceanfront view and the client’s desire.

| (Photos by Alan Weintraub/Arcaid) |

I bring up this U.S. project because the moat concept proved acceptable to the local building department: Officials there did not want to appear as though they were resisting creative design, and they accepted our contention that the moat was actually safer as a barrier than a 42-inch high railing would be.

Nowhere in the code does it accept using a pool in place of a railing; in this case, however, the common-sense position was that you would have to jump into the pool – which could happen accidentally – but then you’d have to climb out the other side and jump down again – which could not.

The main point to be taken away from Arango House (and most other Lautner designs) is that there must be a unified approach to the construction of the entire project from the start. This is not a waterfeature that you could even dream of adding on later!

Rather, the key to the feasibility of this design is that the structure of the pool surrounding the house is part of the house. To include such a watershape, it must be there at the concept stage. In most cases, that kind of nascent integration can result only from close cooperation with an imaginative watershaper.

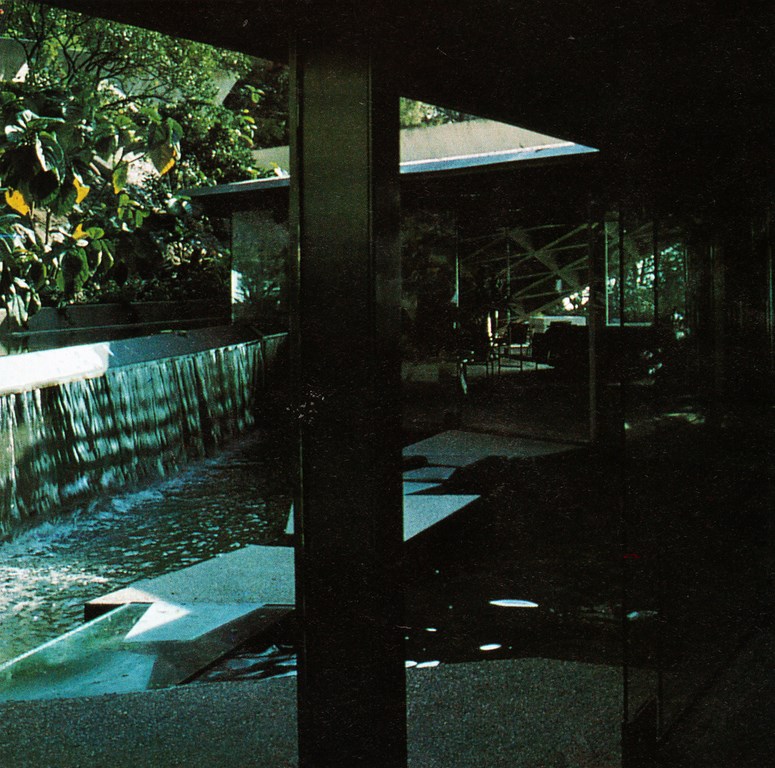

The Goldstein Residence (1973)

When originally built in 1963, this house in Beverly Hills was designed with a swimming pool that had a typical circulation system. The current owner wanted to upgrade the look and the impression made by the pool by bringing the water up to the level of the deck. Of course, it’s much harder to do this sort of remodeling of a pool in an existing deck, because the surface won’t be perfectly level.

| (Photos by David Tisherman, David Tisherman’s Visuals, Manhattan Beach, Calif.) |

To satisfy the client’s desires, we worked with pool designer and builder David Tisherman and often thought how much better off we would have been had a watershaping consultant been involved in the project the first time around. (I discuss the need for professionals in these consulting roles in the sidebar below.)

|

Defining an Opportunity As far as architects and their clients are concerned, there is as yet no clearly defined role in the design process for a watershaping consultant. We have access to professionals who advise us on landscape and lighting design, for example, but we’re left to our own resources when it comes to finding assistance in implementing the design of swimming pools, ponds and other waterfeatures. In fact, only the fountain segment of the watershaping business offers these kinds of services. As a result, we usually end up working directly with contractors. That can be awkward, because a great deal of time often passes between the initial design work and the completion of the job – and many contractors do not see it as being in their interest to participate from the beginning in a project that may or may not even happen or in which it is possible someone else will get the job. I believe this situation has become a barrier to watershapers who want to attain a status and a role that should be theirs in the greater design community. The same way architects have access to electrical and mechanical engineers, we should be able to call on consultants for our watershapes. Believe me, as one who has spent a career working as the coordinator of design teams that encompass a range of disciplines, I would love to bring in watershapers to contribute their expertise to the process. They could contribute great ideas to great projects and be compensated at a fair rate for their time or designs on the same basis as other design-team participants. Just as architects are not always the builders, design consultants may not turn out to be the contractors. Nonetheless, they would have the opportunity and honor of having their names forever associated with fantastic projects and receive full credit for their ideas. This new breed of consultant would have to know his or her stuff and be able to put plans on paper, ready for bid. This calls for a high level of technical expertise, because the designer isn’t necessarily the one who will execute the plan. Speaking for myself, I’m thrilled by the potential this consulting concept has. The overall project can gain from the sophistication of the ideas and refinement of designs coming from this sector. And in receiving a fair fee for the work, the consultant can spend the time required to research ways of making new ideas work – energy-saving ideas, aesthetic enhancements, technical advancements and more. To get this kind of support from someone who has spent a career developing ideas and exploring technical questions would be wonderful. To those of you out there who are heading in this direction, I urge you to keep at it: There is much we might do together! – H.A. |

The retrofitted pool is spectacular and has appeared as a focal point in movies and countless advertisements through the years, but it’s not the only watershape in the home. In fact, the pond that you have to cross to enter the house, with glass bridges spanning over stepping stones, is at least as significant as the pool because of the way Lautner used it to create drama and continuity.

He filled the pond with koi. The color and movement they lend to the setting are important to the overall effect.

Both watershapes fit perfectly into the overall geometry of the residence. The triangles and triangular patterns seem lightweight, almost floating – a product of the owner’s desire to capture the sensation of floating and of what Lautner saw in the site. The result is a soaring set of beautiful shapes.

With all of these things, you always have in mind how they are going to work structurally. The most beautiful design in the world isn’t worth anything if you don’t know how to create the shapes and spaces you want on a permanent basis. We use concrete in our projects as a result, because it’s good for curved shapes. You can build a very thin structure that is very rigid; it is also a durable, maintenance-free material.

Those structural factors are clearly important – and present another case in which active, early participation by a watershaping consultant would be invaluable: With the participation of such a professional, the feasibility of the design can be considered from the start by someone with expertise in constructing systems that contain, move and treat water.

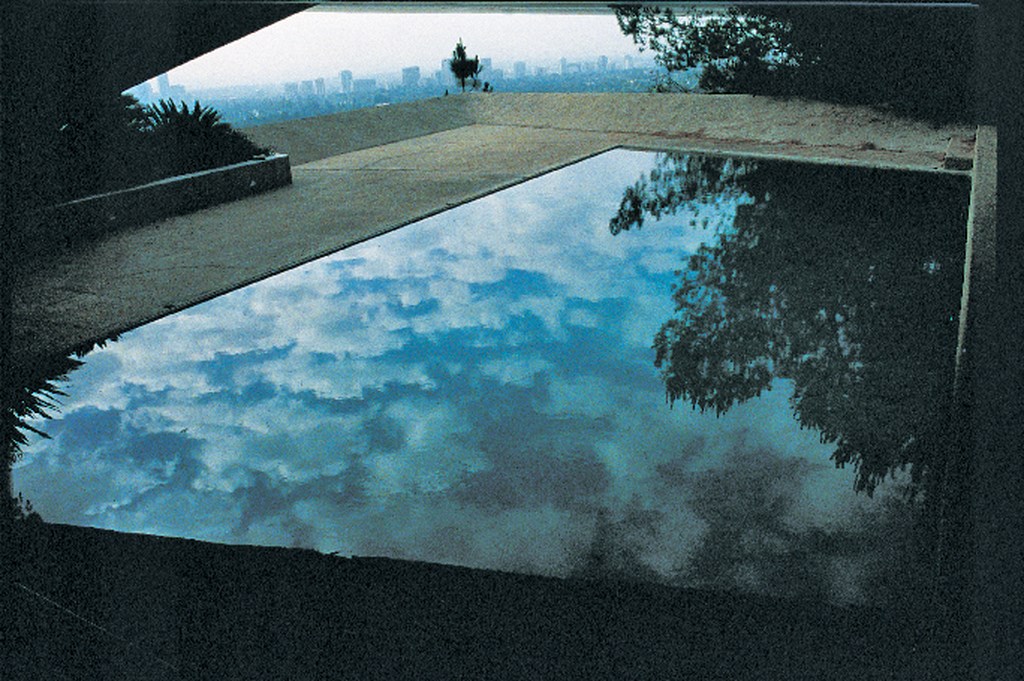

Silver Top (1958)

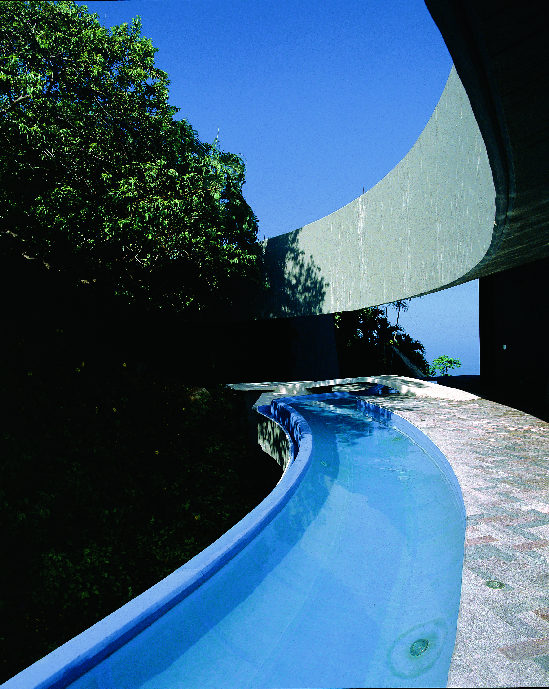

The design here is a perfect melding of site and view. The lot overlooks Silverlake Reservoir, just north of downtown Los Angeles. The presence of that body of water prompted John Lautner to create a pool that offers a sense of unlimited connection between site and space, just as vanishing edges are used today. This connects the curved house – through the similarly curved pool – to the view of the reservoir beyond.

As you walk through the house, you see almost immediately that there’s water at the other end, and it acts like a magnet: Everybody is driven to go out onto the deck, where they turn and see the reservoir and then take advantage of seating built in at just the right location.

The pool is the earliest vanishing-edge design of which I’m aware. It was a very distinctive detail and certainly the topic of conversation among people who visited there for many years. Now, of course, vanishing-edge details are fairly common, but that was far from the case when Silver Top was built.

| (Photos at left and right by Michael Nantz, Elite Concepts, Dallas, Texas; at middle by David Tisherman) |

This home is an example of a space where you really have to walk through the environment to get the feeling provided by the whole design. To be sure, this is true with all thoughtful architecture, but is used to great effect in this home, where you are drawn through the environment by the presence of the water and meet a surprise at every turn. It lends glamour, beauty and intrigue to the composition.

Controlling access to views with walls and greenery and water let you maintain this sense of surprise. Every changing element, including the reflective qualities of the water and available light at different times of day, all work to make the overall impression of constant change and a process of discovery.

I’ve heard from many of the clients who worked with John Lautner that the nature of the environment he created for them has contributed to their lives. Many of these homes have been occupied by creative people – artists and writers and film makers – and they have told me that Lautner’s work and mine have inspired them. There could be no greater compliment to a proponent of organic architecture, and no greater affirmation that the approach works time and again in designs unique to each site and client.

I can only imagine how different and more effective our work might have been had we been given access to knowledgeable, creative, innovative watershaping consultants who were skilled in hydraulics and waterfall weir design and who kept up to date on the best equipment and water treatment, waterproofing and finish materials. (In addition to creative design, this is also about quality products.)

Such consultants could have led us to weigh new possibilities and options we would never have considered on our own – and helped us apply our creativity in a host of new ways.

Helena Arahuete is the principal architect at John Lautner Associates/Helena Arahuete Architect, an international design firm based in West Hollywood, Calif. Born in Belgium and raised in Argentina, Arahuete graduated from the University of Buenos Aires and began her professional career with architecture, engineering and construction firms in Argentina. She came to the United States and began work with Lautner’s world-renowned firm in 1971. She served as project architect for many of the firm’s projects and was Lautner’s associate architect at the time of his passing in 1994. Arahuete continues to design custom homes for clients, mostly in the Western United States. Many of her designs have been featured in architectural publications. She is routinely invited to give lectures by universities and institutions, including (among many others) the University of California at Los Angeles, Taliesin, the American Institute of Architects and Genesis 3’s Level Two Design School.

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

To see what happens when a watershape is completely, entirely, organically linked to architecture, you need look no farther than the work of John Lautner and many of the projects he completed before his death in 1994. Mentored by Frank Lloyd Wright, Lautner saw swimming pools and other waterfeatures as integral components in compositions of great and enduring beauty, says Helena Arahuete, who was in turn mentored by Lautner and is now the principle architect in the firm that bears his name. (Photo by Alan Weintraub/Arcaid)

Helena Arahuete joined the staff of John Lautner’s architectural firm in the early 1960s, at a point where he was turning out some of his most spectacular work. Indeed, Lautner can indisputably be said to have designed some of the most beautiful and unusual homes built in the second half of the 20th Century.

An apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright’s who studied with the master at Taliesen, Lautner was an exponent of the philosophy and discipline known as “Organic Architecture,” an approach Arahuete, now an eminent architect in her own right, has continued to use and refine while running the firm that still bears Lautner’s name.

She is now one of the world’s leading practitioners of Wright’s and Lautner’s approach to creating unique structures that are intricately and intimately tied to their surroundings. She is also so firm a proponent of the integration of watershapes into those architectural forms that in April 2000, she carried her message to the first Genesis 3 Level II Design School, held in Islamorada, Fla. – and welcomed an opportunity to present some of Lautner’s work here by way of defining the place watershapers have at the design table with the world’s great architects.

John Lautner always said, “Use nature as a source.”

That was his starting point. His designs were then inspired by the sites on which he worked, so each is unique and cannot fit anywhere else. That’s part of what organic architecture is all about: designing structures uniquely suited to their surroundings. It’s the far opposite extreme from a one-size-fits-all mentality.

And just as much of the individuality comes from clients as it does from the sites: In each case, Lautner interviewed them, uncovered their personal likes and dislikes and took all of this into account during all phases of the project. I do the same, and find it to be inspiring because every person is different, with different sensitivities, and you find endless sources of creativity and ideas by talking to them.

In the process, you’ll find some people who are more comfortable with elegant designs and lightweight, angular, cantilevered shapes. Or you’ll find clients who are interested in curved, sheltering spaces. In time, what you learn is that what might work for one client might not work so well for somebody else – and learn to celebrate the differences rather than perceive them as obstacles to be overcome.

These clues you get from your clients direct you to do things that are totally individualized. It forces you not to copy, not even from yourself, and to do things that are totally fresh. Just as each client is one of a kind, so is each site with its unique setting and views.

Using Views

One of the primary things the site gives you is the view.

This was always a major factor in John Lautner’s work, and it’s certainly something I consider in my own. We take the best the site has to offer in terms of views, be they distant views or nearby, then we choose the areas we want to be seen from inside the home – and also select what should not be seen.

If you frame the view a certain way, it becomes a work of art – but a work of art that is never the same and constantly changes with the light of day, the seasons, the clouds, the position of the sun and light filtering through trees or casting shadows over ground and rocks. Within each site itself there is constant variety.

When you consider the view from inside the house, even a relatively ordinary view can be made to be far more interesting – and can benefit from appropriate placement of a watershape, for example. The key for the architect is to approach the design of the home or the space from the inside out. And I believe that this approach will work as well for watershapers who take an interest in orchestrating views and lines of sight.

This is something I constantly try to explain in lectures and classes, this idea that architecture is taken from the space surrounding a person who stands within a space and is something that develops outward.

In fact, this special perspective is what architecture is about and what separates it from other art forms. With a painting, for example, you stand in front of it and view the image in two dimensions. Sculpture offers a third dimension: You can walk around it, but you are still outside the work. In all forms of architecture, be they interior or exterior, you are inside the work, inside the sculpture.

To form a space around someone, you need to be aware of the experience that someone will have while inside this environment. To be effective in creating spaces for people to enjoy, you need to be aware of things such as scale and the relationship between differently shaped spaces.

If, for example, you move through a corridor with a low ceiling, this makes you feel a certain way. Then if you move from that corridor into a much larger space, the way you feel is transformed. You will physically feel the space and how it is affecting you in a certain way.

If you are able to capture that influence in the way you shape an environment, I believe you’ve really achieved something.

PERFECT COMPANIONS

This designing from the inside out – that is, from the perspective of the person in the space – encourages the designer to use natural forms and complementary forms inspired by nature to create the experience of the person inside the environment.

In this respect, water is a very important element in design.

I’ve designed a project, scheduled to break ground soon, that has a long body of water with long benches right behind it. The idea here is simple: We want people to be able to sit next to the swimming pool while experiencing a spectacular view off into the distance.

By creating a place for someone to sit next to the pool with an unobstructed line of sight to the distant view, we are able in a very simple and straightforward way to bring the immediacy of the water together with the vista. In other projects, we’ve used structures with pools adjacent to sloped areas to block the view of objects at lower sight lines while framing the distant view along the far edge of the water.

There are countless other ways to integrate water into architectural programs, and Lautner used many of them in his long career. Using the photographs on these pages, let’s consider the use of water in three of Lautner’s projects. I’ll also offer some insights into his philosophical roots. Perhaps most important, I’ll offer my own perspective on a role for the watershaping consultant in the future of architectural design.

sidebar 1

Roots

The philosophy that drove the work of architect John Lautner, called organic architecture, is the philosophy of Frank Lloyd Wright and other great modern architects who have followed in Wright’s footsteps.

Organic architecture is not an easy thing to summarize, because it means different things to different people. My own interpretation is that it is an expression of what happens in nature, where everything that’s living is designed for a purpose. Animals, for example, have skeletons, skin and coloration; they are beautiful and they make sense. The same is true of other natural forms, such as trees or even geological features such as rock outcropping and rivers. They also have specific forms that serve a purpose and make sense.

In our architecture, we strive for forms that similarly serve purposes and make sense and revel in the fact that the ideas never get stale or become commonplace. Styles and trends will come and go, but philosophy endures. You can’t say you’ve seen a “Victorian” mountain or a “Chippendale” tree: Their designs and purposes are timeless and enduring in their beauty and purpose. They are beautiful because of the way they are.

In that sense, organic architecture is a genre that transcends genre. That’s the ambition of great architects including Wright and Lautner – and can apply just as surely to the work of watershape designers and builders.

– H.A.

sidebar 2

Inspiration and Influence

John Lautner had a tremendous amount of respect and admiration for Frank Lloyd Wright and apprenticed under him in the 1930s at Taliesen, one of the great incubators for 20th-century architects and designers.

While there, Lautner learned by doing, but he possessed sufficient vision on his own to understand the concepts behind the Wright philosophy and apply them in new and personal ways.

Lots of people who apprenticed with Wright ended up following the shapes and contours of his designs – ornamental but deprived of spirit. Not Lautner: He took on the philosophy and Wright’s influence and found that with it, you could create totally original projects each and every time. In working with him and since his death, I try to do the same.

You are unique, your influences are unique, the site is always unique and so is the client. The combination of these four factors is what leads to original forms of expression in processes that apply across all creative fields – including the design of watershapes.

– H.A.

sidebar 3

Defining an Opportunity

As far as architects and their clients are concerned, there is as yet no clearly defined role in the design process for a watershaping consultant.

We have access to professionals who advise us on landscape and lighting design, for example, but we’re left to our own resources when it comes to finding assistance in implementing the design of swimming pools, ponds and other waterfeatures. In fact, only the fountain segment of the watershaping business offers these kinds of services.

As a result, we usually end up working directly with contractors. That can be awkward, because a great deal of time often passes between the initial design work and the completion of the job – and many contractors do not see it as being in their interest to participate from the beginning in a project that may or may not even happen or in which it is possible someone else will get the job.

I believe this situation has become a barrier to watershapers who want to attain a status and a role that should be theirs in the greater design community.

The same way architects have access to electrical and mechanical engineers, we should be able to call on consultants for our watershapes. Believe me, as one who has spent a career working as the coordinator of design teams that encompass a range of disciplines, I would love to bring in watershapers to contribute their expertise to the process.

They could contribute great ideas to great projects and be compensated at a fair rate for their time or designs on the same basis as other design-team participants. Just as architects are not always the builders, design consultants may not turn out to be the contractors. Nonetheless, they would have the opportunity and honor of having their names forever associated with fantastic projects and receive full credit for their ideas.

This new breed of consultant would have to know his or her stuff and be able to put plans on paper, ready for bid. This calls for a high level of technical expertise, because the designer isn’t necessarily the one who will execute the plan.

Speaking for myself, I’m thrilled by the potential this consulting concept has. The overall project can gain from the sophistication of the ideas and refinement of designs coming from this sector. And in receiving a fair fee for the work, the consultant can spend the time required to research ways of making new ideas work – energy-saving ideas, aesthetic enhancements, technical advancements and more. To get this kind of support from someone who has spent a career developing ideas and exploring technical questions would be wonderful.

To those of you out there who are heading in this direction, I urge you to keep at it: There is much we might do together!

– H.A.

The Arango House (1969)

In the design of unlimited space, you have the opportunity to continue the inside to the outside and vice versa. The Arango House is an example of what can be done when the horizon is literally the limit – and of how the water plays an important role in creating and capturing this experience.

The site offers a beautiful view of the Acapulco Bay; and Mr. Lautner wanted to find a natural way to integrate the home’s exterior with this fantastic view. The moat, a truly unique feature at that time, wraps all the way around the home’s second floor with a vanishing edge overflowing into a gutter. All you see at deck level is the water disappearing into the water of the bay beyond.

At the same time, the moat is a safety device. Rather than having a railing, which would have disrupted the view rather than connect the home to it, you have this expanse of water that prevents people from falling off the cantilevered deck while still bringing the outside and the inside together. The pool is six feet wide and four-and-a-half feet deep, and the effect is breathtaking. You can literally swim around the house.

We had another client who had visited the Arango house and wanted the same thing for his house in Malibu, Calif. We didn’t like the thought of repeating a design we’d done in the past, but we consented to do so given the oceanfront view and the client’s desire.

I bring up this U.S. project because the moat concept proved acceptable to the local building department: Officials there did not want to appear as though they were resisting creative design, and they accepted our contention that the moat was actually safer as a barrier than a 42-inch high railing would be.

Nowhere in the code does it accept using a pool in place of a railing; in this case, however, the common-sense position was that you would have to jump into the pool – which could happen accidentally – but then you’d have to climb out the other side and jump down again – which could not.

The main point to be taken away from Arango House (and most other Lautner designs) is that there must be a unified approach to the construction of the entire project from the start. This is not a waterfeature that you could even dream of adding on later!

Rather, the key to the feasibility of this design is that the structure of the pool surrounding the house is part of the house. To include such a watershape, it must be there at the concept stage. In most cases, that kind of nascent integration can result only from close cooperation with an imaginative watershaper.

(Photos by Alan Weintraub/Arcaid)

The Goldstein Residence (1973)

When originally built in 1963, this house in Beverly Hills was designed with a swimming pool that had a typical circulation system. The current owner wanted to upgrade the look and the impression made by the pool by bringing the water up to the level of the deck. Of course, it’s much harder to do this sort of remodeling of a pool in an existing deck, because the surface won’t be perfectly level.

To satisfy the client’s desires, we worked with pool designer and builder David Tisherman and often thought how much better off we would have been had a watershaping consultant been involved in the project the first time around. (I discuss the need for professionals in these consulting roles in the sidebar on page 43.)

The retrofitted pool is spectacular and has appeared as a focal point in movies and countless advertisements through the years, but it’s not the only watershape in the home. In fact, the pond that you have to cross to enter the house, with glass bridges spanning over stepping stones, is at least as significant as the pool because of the way Lautner used it to create drama and continuity.

He filled the pond with koi. The color and movement they lend to the setting are important to the overall effect.

Both watershapes fit perfectly into the overall geometry of the residence. The triangles and triangular patterns seem lightweight, almost floating – a product of the owner’s desire to capture the sensation of floating and of what Lautner saw in the site. The result is a soaring set of beautiful shapes.

With all of these things, you always have in mind how they are going to work structurally. The most beautiful design in the world isn’t worth anything if you don’t know how to create the shapes and spaces you want on a permanent basis. We use concrete in our projects as a result, because it’s good for curved shapes. You can build a very thin structure that is very rigid; it is also a durable, maintenance-free material.

Those structural factors are clearly important – and present another case in which active, early participation by a watershaping consultant would be invaluable: With the participation of such a professional, the feasibility of the design can be considered from the start by someone with expertise in constructing systems that contain, move and treat water.

Photos by David Tisherman, David Tisherman’s Visuals, Manhattan Beach, Calif.

Silver Top (1958)

The design here is a perfect melding of site and view. The lot overlooks Silverlake Reservoir, just north of downtown Los Angeles. The presence of that body of water prompted John Lautner to create a pool that offers a sense of unlimited connection between site and space, just as vanishing edges are used today. This connects the curved house – through the similarly curved pool – to the view of the reservoir beyond.

As you walk through the house, you see almost immediately that there’s water at the other end, and it acts like a magnet: Everybody is driven to go out onto the deck, where they turn and see the reservoir and then take advantage of seating built in at just the right location.

The pool is the earliest vanishing-edge design of which I’m aware. It was a very distinctive detail and certainly the topic of conversation among people who visited there for many years. Now, of course, vanishing-edge details are fairly common, but that was far from the case when Silver Top was built.

This home is an example of a space where you really have to walk through the environment to get the feeling provided by the whole design. To be sure, this is true with all thoughtful architecture, but is used to great effect in this home, where you are drawn through the environment by the presence of the water and meet a surprise at every turn. It lends glamour, beauty and intrigue to the composition.

Controlling access to views with walls and greenery and water let you maintain this sense of surprise. Every changing element, including the reflective qualities of the water and available light at different times of day, all work to make the overall impression of constant change and a process of discovery.

I’ve heard from many of the clients who worked with John Lautner that the nature of the environment he created for them has contributed to their lives. Many of these homes have been occupied by creative people – artists and writers and film makers – and they have told me that Lautner’s work and mine have inspired them. There could be no greater compliment to a proponent of organic architecture, and no greater affirmation that the approach works time and again in designs unique to each site and client.

I can only imagine how different and more effective our work might have been had we been given access to knowledgeable, creative, innovative watershaping consultants who were skilled in hydraulics and waterfall weir design and who kept up to date on the best equipment and water treatment, waterproofing and finish materials. (In addition to creative design, this is also about quality products.)

Such consultants could have led us to weigh new possibilities and options we would never have considered on our own – and helped us apply our creativity in a host of new ways. Photos at left and right by Michael Nantz, Elite Concepts, Dallas, Texas; at middle by David Tisherman)

Helena Arahuete is the principal architect at John Lautner Associates/Helena Arahuete Architect, an international design firm based in West Hollywood, Calif. Born in Belgium and raised in Argentina, Arahuete graduated from the University of Buenos Aires and began her professional career with architecture, engineering and construction firms in Argentina. She came to the United States and began work with Lautner’s world-renowned firm in 1971. She served as project architect for many of the firm’s projects and was Lautner’s associate architect at the time of his passing in 1994. Arahuete continues to design custom homes for clients, mostly in the Western United States. Many of her designs have been featured in architectural publications. She is routinely invited to give lectures by universities and institutions, including (among many others) the University of California at Los Angeles, Taliesin, the American Institute of Architects and Genesis 3’s Level Two Design School.