Off the Deep End

A big part of properly designing watershapes to meet specific client needs has to do with understanding how they’ll be using the body of water.

I always explore this issue with my clients, which is why, for the most part, I don’t do many pools with traditional deep ends – despite the fact that, for decades, most pools have been built with them. To me, in fact, the whole concept of deep water in residential swimming pools is basically misguided and largely obsolete.

Consider exactly what it is that bathers can do in the deep end of a pool: They might dive, tread water or swim to the bottom to retrieve coins or pool toys – and, unfortunately, they can drown there, too. Yes, people also drown in shallow water, but there’s no doubt that deeper waters provide

greater levels of risk and hazard for non-swimmers, inexperienced swimmers or small children.

On a less dramatic but still-significant level, deep ends require a bit more effort to clean and, because they expand the overall volume of water in a given pool, increase the cost of both heating and chemical treatment. In many cases, deep water also comes with dramatic temperature variations that can make exploring the depths an unpleasant experience.

By contrast, shallow ends provide a far greater variety of recreational opportunities, from playing with small children to games of volleyball or basketball. Even a classic game like Marco Polo is facilitated by shallower water. Shallow water is also perfectly adequate for lap swimming and ideal for swimming instruction.

FLAT OUT

Assuming that the majority of aquatic play, exercise and relaxation take place in shallow water, it’s also a given that large percentages of children and adults will, given a choice, spend most if not all of their time in the shallows or on beach entries, steps, benches or thermal ledges.

Even the big commercial and institutional watershapes get this: Most of recent vintage include big shallow areas because designers and managers all know that the presence of these waters increases the utility of almost any watershape.

That said, I do occasionally build a deep end into a pool when the client wants one – in about one out of ten projects (and probably less) these days. It’s usually a family with teenage kids or grandkids that wants an area with diving rocks, for example – a situation that requires deeper water for safe diving.

To that point, let’s be clear that a great deal of pool-industry research has gone into the issue of how potentially catastrophic diving accidents can be avoided. For any body of water meant for forms of exercise or play that involve diving, standards for depth requirements should always be followed.

More and more these days, however, when push comes to shove my clients are telling me that they neither want nor need deep water – that’s definitely the trend. As a result, most of my projects for new vessels are now for what I’d call “play pools” with depths between three-and-a-half and four-and-a-half feet. I’ve also seen in my remodeling work that many of my clients want to see their pools brought up to nearly uniform shallow depths.

This brings me to the subject of this column: In some respects, raising the floor of a deep end is a straightforward process, but as is the case with most everything in the art of watershaping, there’s a right way and wrong way to get the job done.

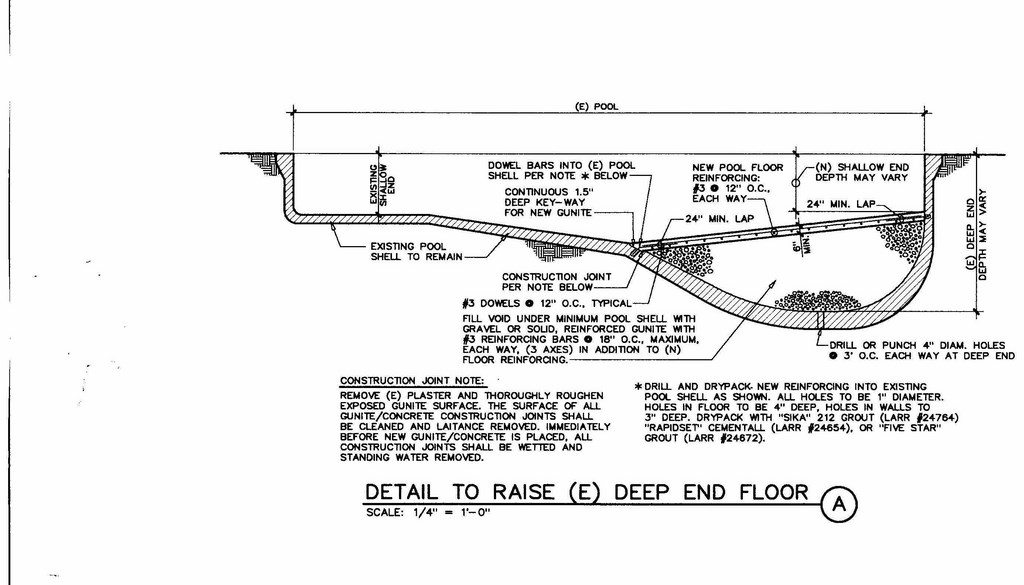

| Even with something seemingly as simple as raising the floor of an existing pool, I always consult my structural engineer and make certain the work on site is done in accordance with his recommendations. The key here is the cutting of a notch in the old shell to ensure that the new concrete is of adequate thickness where it meets up with the original structure. |

Let’s start with the basics: Those of us familiar with concrete know that it is invariably stronger with steel than it is without steel. We also know that steel prevents shrinkage, meaning that, when you raise the bottom, it should be done using structural steel along with the poured concrete, shotcrete or gunite. Filling in the depths with an un-reinforced mass of cementitious material will surely lead to failure through cracking or delamination or both.

If you’re among those who persist in adding yards of new material to pool bottoms (or benches or steps, for that matter) without structural steel, it’s time to change your approach. (If Rule 1 is that steel goes into everything, then Rule 2 is that you never use rebound, period.)

SIMPLE STEPS

You should never install new concrete over an existing plaster finish, so I always start the process by chipping out the existing finish.

Once that’s done, I chisel a notch two to three inches deep around the full perimeter of the pool where the new material will interface with the existing shell. My intention here is to create a substantial cut that will accept the edge of the new concrete.

Look at it this way: The contour of most pool bottoms is formed to create a smooth transition from deep to shallow areas. When you apply new concrete to that taper as is, the fresh material will become thinner and thinner as new work is feathered into old.

|

Sage Advice If I may make one more important point related to “uplifting” projects of the sort discussed in the accompanying text, let me say that even for a comparatively simple detail such as raising a pool floor, I always consult my structural engineer, Mark Smith – a good friend and the best structural engineer for pools I’ve ever known. In my view, any detail in a remodel or new construction requires the input of a structural engineer, and I consider mine to one of my most important allies in any design/construction process. Generally speaking, I see structural engineers’ input and a properly devised structural plan as an insurance policy: No matter how simple the detail may be in concept or execution, there is no substitute for certainty when it comes to the structural design. — D.T. |

If you’re doing things that way, consider this: With feathering, the concrete becomes a half-inch think, then an eighth-of-an-inch thick, then a thickness so minuscule you’d need a micrometer to measure it. That accomplishes nothing, because there will be a delamination bonanza along the edge of the new concrete.

What I do by chipping out a notch is create a pan in which the new concrete will never be less than a couple of inches thick. When paired with steel – I use #3 bars at 12-inch intervals in both directions, with vertical bars as well if we’re pouring more than a foot of new concrete – a much more reliable structure will result.

Anyway, once the old finish has been cleared, I mark the shell with spray paint to indicate the location of the notch. We established that level using a transit, measuring down from the waterline of the pool. We then chip out the marked notch all the way around the perimeter of the new bottom.

Next we drill holes in the bottom of the pool and insert new steel, locking it into place with hydraulic cement. In conjunction with the notch, this new steel essentially creates a form. We then either pump in concrete or apply gunite or shotcrete to fill the bottom. Now the thinnest material we will have at any point on the new floor is two inches thick.

In most remodeling situations, I had no involvement in building the pool in the first place and don’t know the caliber of the construction. If it has been holding water successfully, I don’t want to do anything to compromise the shell, which is why I seldom (if ever) use an approach in which holes are punched in the bottom of the old shell and gravel is inserted as a “form” over which a final layer of gunite or shotcrete is applied.

In all cases, my floor-raising projects involve the pouring of new concrete into the entire void – and I do so in full consultation with my structural engineer. (For more on the value of this input, see the sidebar just above.)

MULTIPLIED BENEFITS

I seldom view raising a pool’s floor as a single task: In most cases, such a project will enable us to upgrade a variety of plumbing details as well.

This floor-raising procedure, for example, generally provides enough room for installation of a new, split main drain that will minimize the risk of suction-entrapment incidents. And if raising the bottom is accompanied (as it often is) by the addition of new benches or steps, the new space in those structures allows for a complete system overhaul.

If you use those new benches or steps to carry new plumbing behind their steel, for instance, you have a golden (and comparatively affordable) opportunity to upsize smaller plumbing, redo the lighting, add new steps or benches and create a new circulation system that will have much greater efficiency – all encased in steel and concrete per industry standards and all accomplished without compromising the structural integrity of the original shell.

David Tisherman is the principal in two design/construction firms: David Tisherman’s Visuals of Manhattan Beach, Calif., and Liquid Design of Cherry Hill, N.J. He can be reached at tisherman@verizon.net. He is also an instructor for Artistic Resources & Training (ART); for information on ART’s classes, visit www.theartofwater.com.