Thoughts for the Eyes

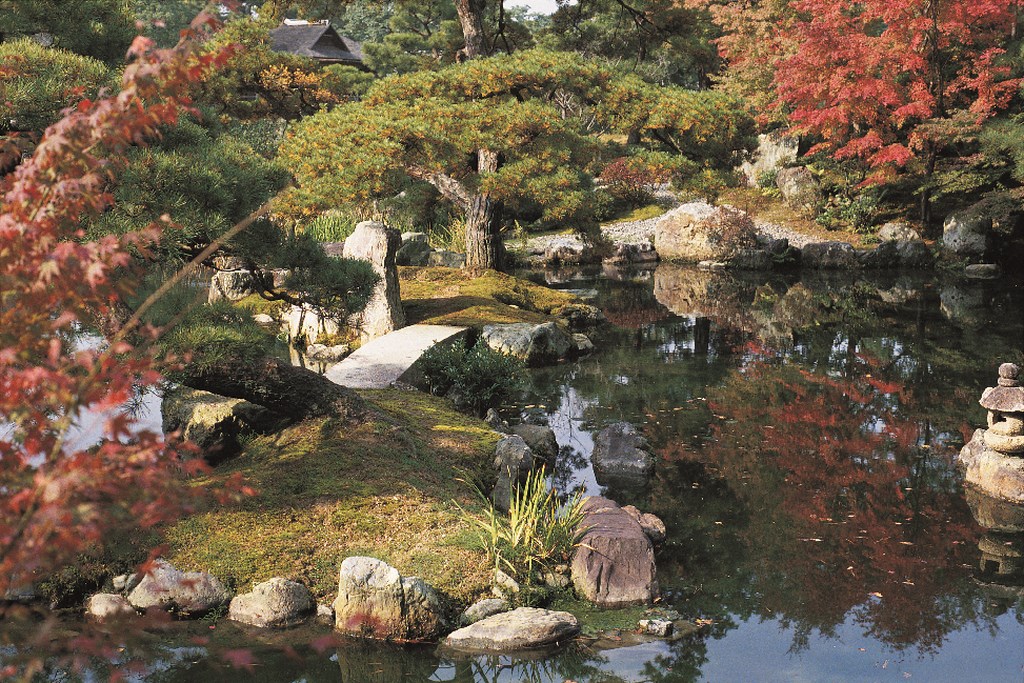

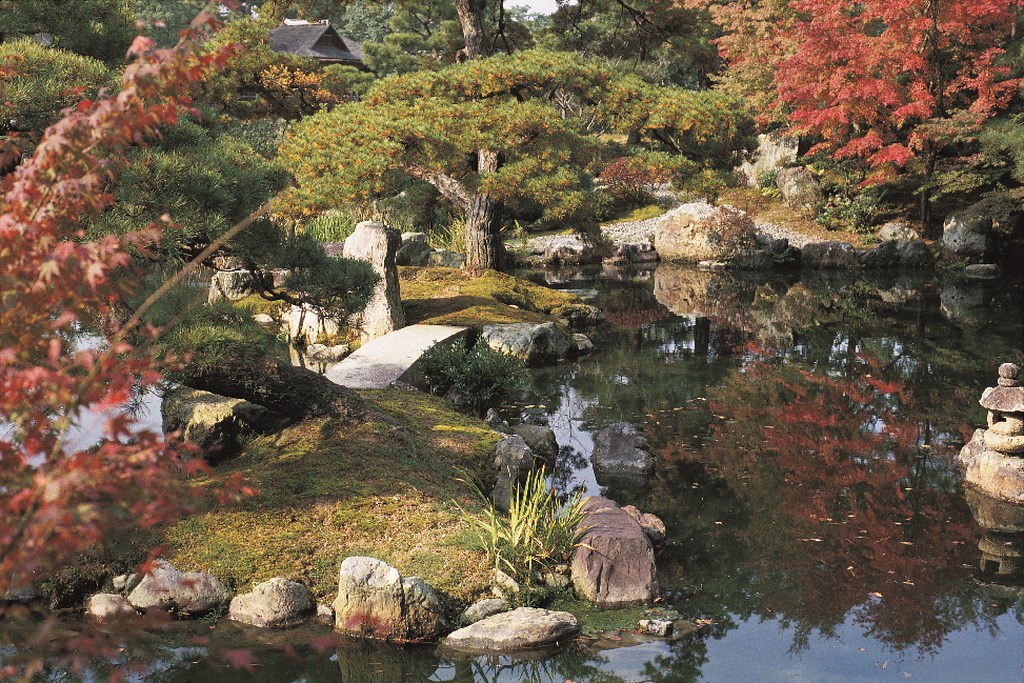

Home to some of the world’s greatest outdoor spaces, Kyoto, Japan, is a garden lover’s heaven. If you make the trip, however, there is one garden that stands above all others – an aesthetic treasure, a nature-inspired garden masterpiece that is quite possibly the most beautiful place I’ve ever been.

Owned by the Japanese imperial family, Katsura Rikyu (pronounced kah-tsu-rah ree-kyu) is an estate in Western Kyoto near the Katsura River. Rikyu means “detached palace,” but that translation is a little misleading to English speakers, because the estate does not resemble a royal palace in any way. Rather, it is palatial only in a spiritual sense, a space that embodies the highest expressions of balance, harmony and elegance.

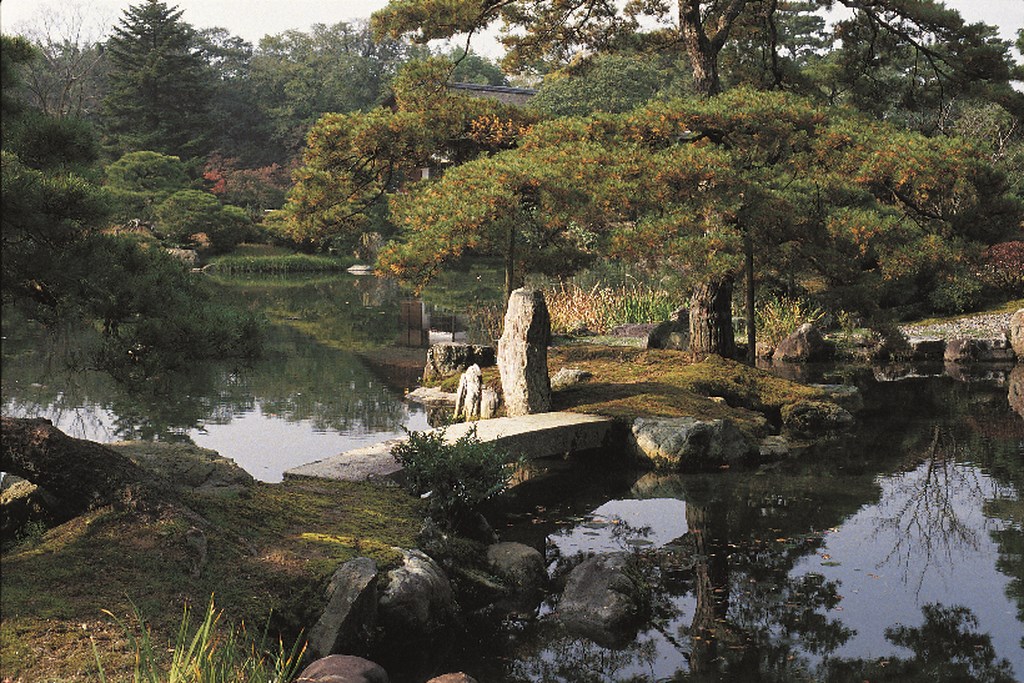

The entire Katsura estate covers about 13 acres. The site includes a large, irregularly shaped pond surrounded by man-made hills and forested areas. Positioned above the pond is the large estate house, which boasts beautiful views of the grounds – each a living portrait. There are also five separate teahouses, each with its own strategic view, and several other buildings scattered about the grounds.

A WALK WITH HISTORY

A winding path that encircles the pond connects the entire site. Guests proceed along this path to find themselves greeted by numerous vistas that gracefully evoke patterns seen in natural landscapes.

On the short walk around Katsura, you experience views of a seaside beach, a deepwater harbor, a dark forest and an open grassy meadow. These areas have all been carefully crafted by the hands of skilled gardeners and have been beautifully tended for centuries. So evocative is the space that the garden has the feeling of a large, carefully composed landscape painting – one you can walk through.

The natural beauty of the place is stunning, literally eye-watering.

The estate was developed by a royal prince and his son in the first half of the 17th Century. Prince Toshihito, a younger brother of the emperor Go-Yozei, had plenty of free time and few (if any) royal duties. Graced with an inquisitive mind, he chose to immerse himself in the study of traditional arts including painting, the tea ceremony and gardening. He owned land in Western Kyoto, and it was there in around 1616 that he began developing his vacation retreat.

| The range of edge treatments at Katsura is awe-inspiring. The gardeners have worked with stone materials ranging from pebbles to great boulders and with a variety of other materials in details that reward exploration of every single foot of the perimeter, both up close and from across the water. |

The development of Katsura was a slow process that stretched over half a century. In this sense, it is a typical Japanese garden, slowly evolving and becoming more refined with each passing year.

The leading garden builder of the era was a government minister named Kobori Enshu. (Enshu was deeply involved the tradition of the tea ceremony and is often credited for extending the “tea aesthetic” into the realms of residential design and landscape gardening. For more about this, see the sidebar below.)

Many English-language books mistakenly state that Katsura was created by Enshu, but this was not the case. Enshu may have played a minor, consulting role, but it is Toshihito himself who deserves the lion’s share of the credit for Katsura’s remarkable design, which he guided carefully until his death in 1629. At that point, Toshihito’s son, Prince Noritada, continued to develop Katsura until he, too, died in 1662.

THRESHOLD OF GREATNESS

The relationship of Katsura to the tea aesthetic is pivotal: The garden is considered a masterpiece not only for its peerless beauty, but also because it played a key role in extending the tea aesthetic to the residential living environment.

In that sense, Katsura is a threshold of sorts: While the Japanese garden tradition is 1,000 years old (and extends through several historical periods), I believe it can be divided into two major epochs – before Katsura and after it.

Before Katsura, Japanese gardens were associated with themes of wealth, religion and power. After Katsura, the gardening art form advanced by incorporating and honoring the culture’s tea-inspired traditions, which are by character modest, secular and inspired by nature.

In that sense, the beauty of Katsura lies not in its grandeur, but in its refinement of an idea and a set of ideals. So, even though it was built by a prince, its main cultural significance is that the principles it embodied eventually found their way into the homes and gardens of regular Japanese citizens.

| The water is important at Katsura, but the whole of the composition is to be savored, including delightfully varied treatments of footpaths and stepping stones as well as distinctive garden structures and teahouses. It’s a process of controlling views and access and perceptions – and focusing the visitor’s attention on the sublime moment at hand. |

Katsura also stands at a historic dividing line for Japan: The garden was developed at the dawn of the Edo Period, which stretched from 1603 to 1867 and represents the start of what is considered the modern era in Japan.

Many of the hallmarks of what we all recognize as “Japanese” gardens were developed or refined during in this modern period, including the characteristic uses of stepping-stone paths, nobedan paving, stone lanterns, bamboo fences, aesthetically pruned trees, grassy foreground areas, water basins, the gogan (zig-zag) edging patterns, teahouse carpentry and the sukiya style.

In many cases, these aesthetic conventions did not originate at Katsura, but many of them are strongly associated with it. So if forced to pick just one threshold where Japanese gardening shifted from an ancient approach to the refined tradition it now embodies, most experts wouldn’t hesitate to choose Katsura.

A MAGICAL WATERSHAPE

The most prominent feature of Katsura’s garden is its large pond. Visitors universally appreciate its beauty, but few understand what makes it so special. The magic of the pond comes not from any one feature or gimmick, but rather from a combination of time-tested design principles that create a convincing, naturalistic effect that is at once elegant and rugged.

The pond has an extremely irregular shape that is impossible to categorize – something akin to a wildly drawn, cursive figure eight with flourishing swirls on each end. The shoreline weaves in and out, creating vantage points that for the most part reveal only one portion of the water’s surface and shoreline at a time.

|

Anyone for Tea? It’s a bit difficult for Westerners to grasp all the subtleties, but it’s important to know that all of Japan’s traditional arts, including architecture and garden design, are heavily influenced by chanoyu, the Japanese tea ceremony. At it’s most basic level, this tradition is about sitting down with friends and family and enjoying a cup of green tea. But in many respects, the tea ceremony is much more than that: It’s an entire philosophy about how to conduct yourself and live in harmony with the world. In Japan, the tea ceremony is an organized ritual, with various schools and traditions in almost every town. Each promotes a slightly different procedure about where and how to enjoy tea – but all, however, emphasize qualities of peace, respect, purity and honor. So powerful is its appeal that, through the centuries, the ethics and aesthetics of the tea ceremony have come to dominate all aspects of traditional Japanese culture. When extended to the residential environment in the time after Katsura Rikyu was developed, the aesthetic manifests itself in unassuming but refined homes and gardens. Katsura itself is built in what is known as the sukiya style. Hallmarks of this style include integration of house and garden; use of predominately natural materials; slender, carefully proportioned wood elements; elimination of ornamentation; and the general suggestion of quiet elegance with rustic overtones. The Sukiya style originated with the tea ceremony. A traditional tea garden is meant to encourage guests to relax and respect the beauty of the four seasons. As they proceed through a tea garden from the entrance gate to the isolated tea area, guests will, it is hoped, put aside any outside worries and enjoy the fullness of the moment. Rather than making bold statements, tea gardens encourage us to be humble and appreciate the natural beauty of the world and our essential oneness with it. At Katsura, these transcendent sensations sweep over you with a welcome ease. — D.M.R. |

It truly does look different from every angle: There are numerous islands, large and small, scattered in various portions of the lake. Dramatic peninsulas also jut into the water, offering further variety and dimension.

There are a variety of edge treatments, as well. Stone plays a prominent role here, and in fact Japanese garden ponds are best known for their handsome rocky shorelines. At Katsura, about half the pond is edged in rocks. When properly placed, stone can be a particularly convincing edging material because it resembles the banks of natural rivers, lakes and seas where moving water has washed away the soil to expose the stone.

Japanese gardeners carefully select the stones they use in their designs. Much like artists working with pigments, these artisans select their materials with painstaking precision and care, working with large boulders, tiny pebbles and every size between.

Most of the edge stone material breaks below the waterline, creating the illusion that the stone extends downward, deep into the earth. Rather than looking deposited, such well-placed stones look as though they have always been there. And to avoid the “necklace” effect of a uniform ring of rocks placed around the water’s edge, Japanese gardeners employ a pattern called gogan-ishigumi, a three-dimensional pattern in which rocks are set in zigzags that move up and down, and in and out.

Other edges around Katsura’s pond include an elegant cobble beach, wooden posts, stone retaining walls, and several areas that display the (difficult to execute!) turf/water knife-edge. In some spots, trees and shrubbery have been trained to hang over the water’s edge, adding an extra dimension of depth and texture.

All of these different treatments combine with the irregular shape to create unending visual interest and a feeling of richness that cannot be achieved with the use of any singular, homogenous edge treatment.

A CONTINUING STORY

Japanese gardens are meant to endure for the ages, ever changing beneath the learned hands of the artists who tend these refined spaces. Katsura is a supreme expression of this living art form.

Whole books have been written about Katsura, and there’s much more to say than can be contained in this brief appreciation. We could talk about the estate’s architecture, for example, and how the garden is also designed to be viewed from inside the residence and teahouses. We could talk about the path and bridge treatments, or the exquisite palette of plantings that grace the grounds in their verdant beauty.

| The gracefulness and delicacy of the gardeners’ grand design at Katsura radiates in every view of the estate – at water level, at elevations, through trees, no matter which way you look, you consume a visual feast that satisfies without going too far. And this sense of balance, harmony and peacefulness has been of service to visitors for nearly 400 years. |

For all that, it’s important to remember that Katsura’s significance relies not on words like “biggest” or “grandest,” but instead floats gently upon the aesthetic ideals of balance, harmony, refined elegance and human scale. It is a princely retreat, but not a grand castle; above all, it’s a magical place where humble wooden structures stand in place of golden or marble fountains – a place where ambition and bold statements found so often in Western cultures are set aside in favor of enlightened emphasis on human sensory needs and natural beauty.

For anyone designing with water, plants, or hardscape, Japan is a wonderful place to study some of the oldest and grandest traditions of design on the planet. Katsura stands apart even in this heady environment, succeeding in reaching the level of the world’s most respected fine art.

Katsura is indeed a masterpiece.

Douglas M.Roth is publisher of The Journal of Japanese Gardening. Widely considered to be America’s leading authority on Japanese pruning techniques, he is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., and served for six years as a naval officer in the Philippines, Hong Kong and Japan. He resigned his commission in 1988 and established The Isshiki Zoo, an English language school for children in Hayama, Japan. After passing the National Language test, he began a five-year gardening apprenticeship in Kamakura and became the first foreigner qualified to practice gardening in Japan. His company, Roth Tei-en, designs and maintains Japanese gardens throughout North America.