Defining Delicate Tasks

The first of this pair of articles mentioned that Julia Morgan had completed the architecture program at Beaux-Arts in Paris in three years rather than the usual five, but I didn’t mention all of the circumstances.

One of the rules of that institution prohibited the instruction of students after their thirtieth birthdays, which seems a totally bizarre limitation to us now but apparently made sense to French academicians at the turn of the 20th Century. Given the delays in her gaining a position at the school, she’d entered the program with the clock ticking and really had no choice but to blast through the program in rapid order.

This Morgan did by completing a design for a huge theater that proved dazzling enough to the school’s hierarchy that she was granted her certification forthwith. So now she became the first woman to pass through the Beaux-Arts architecture program – and had sufficiently impressed one of her instructors that she was hired to work on a project in Paris soon after graduating.

All in all, her Parisian experience was a display of raw confidence and competence that held her in good stead throughout her long career.

SETTING A DIRECTION

More than 80 years after her work on the Neptune Pool was complete, we at Rowley International (Palos Verdes Estates, Calif.) were called in to size up the current state of the vessel and its systems. As reported in the first of this pair of articles (click here), it was now time to make recommendations on how it could be restored to full functionality once issues related to extensive leaks and certain mechanical and aesthetic issues were addressed.

In beginning this process, we had to consider two large and imposing conditions: First, the Neptune Pool is a rare architectural and cultural treasure, so whatever we did could make no material change on any aesthetic level or to any significant mechanical degree. “Modernizing” was not an idea to ponder or a word to be spoken.

Second and more important, the State of California watched every step of the process with hawkish attention to detail and had a refined sense of what it wanted to happen on site – all backed up by the authority to stop anything and everything dead in its tracks for whatever reason might arise. It was, in other words, a challenging bureaucratic environment that required both diplomatic skill and great patience.

One thing we had working in our favor was the fact that the state didn’t see this watershape as a swimming pool per se: It was a water-filled vessel, to be sure, but it was not to be used for swimming or bathing or any other immersive activity and therefore was exempt from pertinent health codes and regulations related to signage and other issues that complicate public pool and fountain projects.

| As we continued with our engineering evaluations and made our recommendations, it was fascinating to observe the care and precision with which the Hearst Castle staff picked up and removed fountain statuary in preparation for restoration work within the pool. Seeing these precious objects up close and from unusual angles was a distinctive treat. |

This had definitely not been the case for our work a few years earlier on a pool Julia Morgan had designed and built as part of the Marion Davies estate in Santa Monica, Calif. In that case, the pool was to become the heart of a community center and was very definitely subject to all sorts of rules, from the inclusion of depth markers to stainless steel railings that likely would’ve offended the pool’s original designer. Happily, we were granted a variance that let us keep that pool’s amazing interior tile, but for the most part we had to play by the rules no matter the aesthetic consequences.

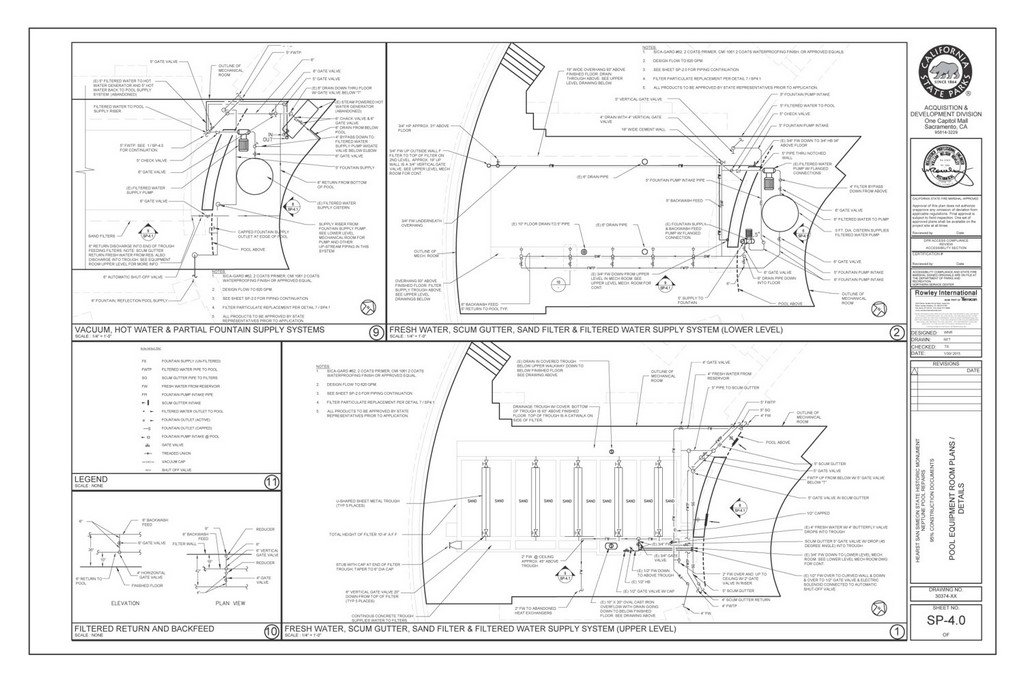

Without that substantial burden with the Neptune Pool, we were effectively freed to take the least intrusive approaches imaginable: We could replace old, failing ferrous pipes, fittings and valves with Schedule 80 PVC versions, for example, without changing anything having to do with the functioning of five old open-tank gravity sand filters, the gutter system or the water-supply and circulation systems.

The same was true with resurfacing the pool’s interior: No modern health code would permit such elaborate interior decoration in a public pool, but in this case, exact replacement was our task. In short, we were given license to pursue solutions that maintained the pool’s authenticity on every pertinent historic level while setting it up to operate for at least another hundred years.

A GUIDING LIGHT

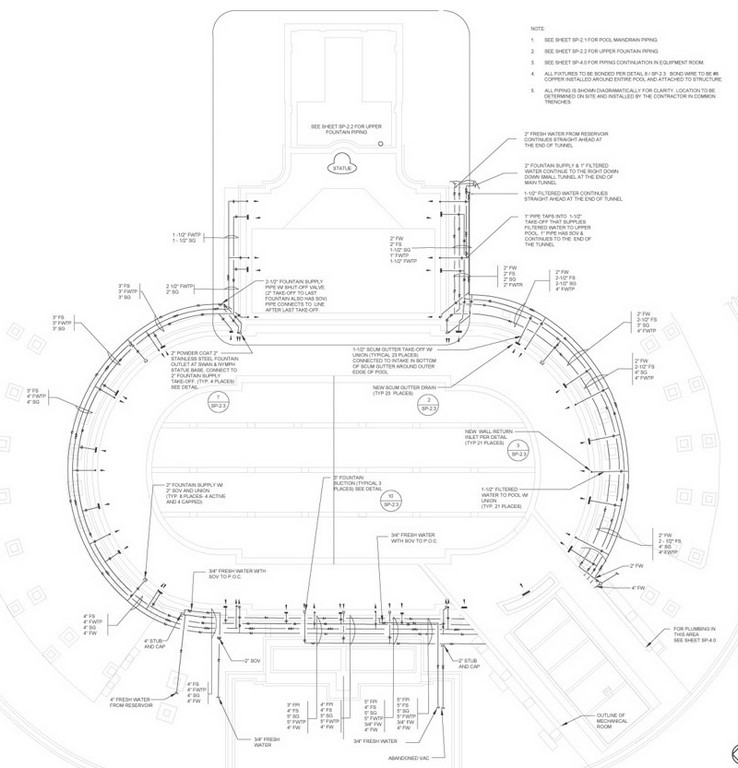

As engineers, our first task was to develop documentation: We needed a set of schematics that would manage the plumbing-replacement process while also offering detailed guidance to anyone who would follow us onto the site, whether it was 2019 or 2099. This meant mapping every inch of the pool’s perimeter and indicating precisely where each run of pipe began and ended.

Next, we indicated certain situations in which substitutions of PVC for iron wouldn’t be exactly one-for-one exchanges. The situation was this: In several places, Morgan has used pipes and fittings no longer in common use. While it would’ve been easy to specify PVC versions of the five-inch pipes she’d selected, for instance, we knew from experience that five-inch fittings are far harder to come by in the full range of configurations we’d need.

| It was a relief to learn that the State of California had decided not to classify this watershape as a ‘public pool’: If they had, someone would doubtless have suggested that the patterned tile should go, that we’d need to order lots of depth markers – and that those glorious marble ladders and railings should go, too, and be replaced by gleaming stainless steel. |

As a result, we upsized these pipes to six-inch diameters, an alteration that required some minor expansion of chases and of penetrations through various walls and into the shell.

We also did some similar substitutions with inch-and-a-quarter pipes and fittings used in the original design, replacing them with two-inch versions. This was a major consideration with the gutter system, where the pool’s operators had let us know that the flow through the gutter’s multiple drops was inadequate. By increasing their diameters even this small amount, that situation was addressed.

As I mentioned in the first part of this article, it was good that the pool was empty through this process. We were able to remove all grates and drain covers and restore them to their original appearance; again, because the usual codes and regulations weren’t to be applied, there was no need to think in terms of compliance with current pool-safety rules regarding hair and suction entrapment.

| There were only a couple instances in which we had to take liberties with Julia Morgan’s mechanical design – and one where we had to deal with a problem of more-recent vintage. For one thing, we recommended replacement of the scum gutter’s original inch-and-a-half pipes with two-inch pipes to correct a long-observed issue with flow. For another, we recommended a complete bonding system for the pool structure – not yet a noted concern by 1936. Finally, we figured out a path that would allow replacement of a previous PVC repair to the pool’s big fountain: They’d painted the pipe to match the wall’s colors, but it was still a visual intrusion that had to be eliminated. |

In only one small way did we do anything that affected the look of the pool as we found it when we walked onto the site: The waterfall/fountain area standing by the pool had at one point been treated to an improvised fix in which a failed system had been bypassed through a reasonably discreet use of a run of PVC pipe.

The repair here involved working from a planted area separated from the fountain basin by a huge staircase. We weren’t present to see how this worked out, but the new lines were inserted on one end and aligned with fittings placed on the other – and so the one major aesthetic blemish we saw anywhere in the poolscape had vanished. Julia Morgan must have been smiling that day.

A LONG ROAD

As was also mentioned last time, the most ambitious task undertaken as part of the pool-restoration process had to do with removing the huge pool’s marble lining and replacing it with all-new material. Happily, the same Vermont quarry is still in operation, so material extracted for use in the restoration was a complete physical match for the original material. (That alone would be enough to bring the average historic-restoration specialist to tears of joy.)

Once the stone was removed, any gaps or cracks in the shell were injected with epoxy. The main problem here was the cold joints that resulted from the pool’s expansion from 1934 to ’36: As discussed last time, there was a considerable flow through these apertures, so much so that stalactites and even complete floor-to-ceiling curtains of minerals had developed on the underside of the shell.

With the gaps filled, the cracks addressed and the pool having been filled to check for watertightness, the substrate could be lined with waterproofing material and would finally be ready for application of new stone. Because it was so directly related to the appearance of a cultural treasure, this was an operation in which the State of California became actively involved: The quarry had wanted to send large slabs of material to the site so it could be cut and fitted with the flexibility required on any surface so large with so many contours.

| The technical drawings we developed offer a practical guide rather than a literal depiction of the way things flowed within the system: We knew where points A and B were, but given the various pinch points, inaccessible zigzags and occasional burials we encountered – some or all of them the result of the 1934-36 remodeling project – we also knew that the plumbers would face substantial challenges in replacing some of the more complicated sections of ferrous pipe with Schedule 80 PVC. |

That wasn’t acceptable to the state: The material was to be milled to standard sizes in Vermont and shipped to the site – a fact that made the installation process take longer as minute adjustments had to be made to work within the shell’s vast dimensions. It was a time when the masons were forcefully reminded that stone can easily be trimmed to fit but that it cannot be stretched to fill a gap!

We weren’t directly involved in this part of the process, but we knew what the masons faced and have nothing but admiration for the fact that their work, at this writing, is nearly complete.

One important “intrusion” the project managers did allow was the complete bonding of the pool system – a deficit we noted early in our forensic examination of the pool’s structure. We would also have liked to install an automatic water-treatment system: By keeping the water balanced, such a system would substantially enhance the longevity of the pool’s interior finish. But that, according to the State of California, would have been a step too far.

Ultimately, this sort of give and take – careful negotiation to align practicalities with a pious sense of historical integrity – is part of what makes this sort of work so challenging and enjoyable. It’s a game of checks and balances, in other words, and I see it as having value in keeping “modernizing” impulses in line. After all, it would be too easy to lose sight of the nature and value of the original and move well past the designer’s intent.

In this case, Julia Morgan was simply a genius and we all knew it would be enough to collaborate with her powerful intellect where we could, then stand back and do whatever we could to leave her achievement alone. Challenging, yes, but always fascinating and deeply rewarding.

Note: From here, the story of completing the restoration project will be picked up in two additional articles from the folks at Terracon, an engineering-services firm based in Olathe, Kans.

William N. Rowley, PhD, is principal at Rowley Forensic Engineers, an aquatic consulting firm based in Palos Verdes Estates, Calif. One of the world’s leading experts on large commercial and competition pools, his most notable projects include partial designs for the competition pools used in the Olympic Games in Munich (1968) and Montreal (1972); he also acted as aquatic consultant for the design of the Olympic Pool Complex in Los Angeles (1984). His projects also have included a wide range of non-competition pools, including the White House pool in Washington, the Navy Basic Underwater Demolition Training Tank in Coronado, Calif., and the resort pool at the Hyatt Regency at Kaanapali Beach on Maui. Rowley is involved in a range of local, state and federal entities, consulting on construction and safety-code requirements. He is also a fellow of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers as well as the recipient of The Joseph McCloskey Prize for Outstanding Achievement in the Art & Craft of Watershaping.