The Art of the Rectangle

This really wasn’t a job for the timid. The ground was unstable, access was limited, and the customer could afford to make massive changes along the way. Other than that, of course, the project was a piece of cake.

The truth is, I enjoy a good challenge. People who know me well are aware that I revel in tackling jobs that test my mettle – and this was definitely one of those cases. Ultimately, it turned out to be one of the most satisfying and beautiful projects I’ve been involved with in a long while.

The site is located on a hillside in West Los Angeles, just a hike downslope from the magnificent J. Paul Getty Center. It’s a picture-perfect spot, and the setting absolutely called for something special. Working closely with the customer, the design we landed on was a stretched, 21-by-49-foot rectangular pool with an attached spa set with a cantilevered deck that juts out into the canyon’s lush greenery.

Yes, you might call it a “basic rectangle.” But as a designer with an appreciation of classic architectural forms, a strong feel for geometry and a sense of design history, I absolutely love that shape and know that it brought out the best in me and my crews as we worked alongside the team the customer had assembled to transform her home.

DRAMATIC VARIATIONS

It comes as a surprise to some that I think the rectangle is the most perfect and beautiful of all pool shapes. To my eye, rectangles are striking in their simplicity and elegant in just about any space. Surrounded and enfolded by beautiful decking, gorgeous tile and warm surface materials, the clean parallel lines of rectangular bodies of water can be absolutely stunning.

Despite their visual simplicity, however, rectangles can be challenging to build. (I’ve heard it said that kidney-shaped pools evolved because mass-market pool builders couldn’t hit square dimensions on the nose.) Even so, I’d argue that if you can’t build a perfect rectangle, you truly don’t belong in the business.

In the case of this particular rectangle, there were several factors that made this job a challenge well beyond the fundamental need to build a vessel that was square and plumb. Soil conditions were awful, which meant we needed a massive concrete-and-steel substructure to go along with some top-flight engineering. And because of the limited access, we’d have to fabricate the 60-foot piles on site and reach over the home with a crane to lower them into the ground. Also, I knew we’d have to form the outer portion of the pool in thin air above a steep slope.

In the case of this particular rectangle, there were several factors that made this job a challenge well beyond the fundamental need to build a vessel that was square and plumb. Soil conditions were awful, which meant we needed a massive concrete-and-steel substructure to go along with some top-flight engineering. And because of the limited access, we’d have to fabricate the 60-foot piles on site and reach over the home with a crane to lower them into the ground. Also, I knew we’d have to form the outer portion of the pool in thin air above a steep slope.

None of these things are terribly unusual, although it does add up to a huge amount of work that needs be done with a high level of precision. What really took this project to an entirely different level, however, were two massive changes the customer asked for midstream.

The first came after we had excavated the pool, set the forms and were well into the process of setting up the piles. That’s when the customer decided that she wanted something “different.” Before long, everything had changed but the basic shape of the pool: The elevations, size, depth – the works.

Luckily, the change afforded some advantages: By raising the level of the pool relative to grade, for instance, a segment of an adjacent structural deck could be used as the roof over part of a wing of rooms that were being added to the lower floor of the home behind a ten-foot retaining wall and the pool. This also let us expand the space available for an equipment room to be located beneath the cantilevered spa at the southern end of the pool.

NOTHING COMES EASY

Of course, we were right in the middle of things when the first change order came through. The rise in elevation also meant that we had to raise the pool two more feet out of the ground – that is, raise the floor, stretch the piles, rethink the grade beams and revisit the plans for the cantilevered deck. It was the right decision in design terms, but it put us to work in a big way.

At this point, we ran into about a month of steady rain, so we had to pull off the job just before the piles were to be set. Actually, this gave us the time we needed to regroup visually and rethink the job.

Because the pool and deck structure were now to be integrated (in part) with the structure of the new wing of the home, we needed to align what we were doing in close communication with the general contractor, his crew and the other trades on site. In fact, if I had to point to a single most important lesson to be learned from this project, it would have to be the value of partnering to work through challenging situations.

Because the pool and deck structure were now to be integrated (in part) with the structure of the new wing of the home, we needed to align what we were doing in close communication with the general contractor, his crew and the other trades on site. In fact, if I had to point to a single most important lesson to be learned from this project, it would have to be the value of partnering to work through challenging situations.

In fact, we needed that partnership to work smoothly every step of the way, because later on, after we had accommodated the first big change and had moved into final stages of construction, the customer changed the scope of the project again, this time asking us to add another section of cantilevered concrete deck off the far side of the pool’s perimeter.

In the original design, the deck cut off about halfway along the far-side length of the pool and left a gap for what was to become a flight of steps leading to the lower portion of the property. That idea was discarded in favor of extending the deck along the full length of the pool – a massive expansion of deck over a sheer, unstable slope, which meant that it had to be fully integrated into the structures we’d already set up.

Again, it was doable – but the engineering had to be rock solid or we’d face the possibility of having tons of concrete and stone tumble down the slope someday.

Some of these spatial relationships are tough to describe in words, so let’s take a pictorial walking tour of the project, start to finish.

A Site to Behold

For all intents and purposes, the project started with a stretch of lawn and dirt in back of a large, rambling house on multiple levels. There was a lot of old brick and flagstone on the existing deck, an existing fire pit and a huge ash tree at the top of the slope — all of which were to come out.

The original plan called for setting the pool about two feet below the level of the original patio adjacent to the house’s upper level and about eight feet above the slope at the far end over the hillside.

The hill sloped off at about 2:1, the bedrock was down at least 40 feet, and we knew massive friction piles would have to be sent down to competent soil to support what ultimately would be a tremendous amount of weight.

Our soils report confirmed our suspicions: There was water moving horizontally through the bedding planes and, as might be expected, chances of failure with anything less than bulletproof construction were exceedingly high.

The Big Dig

Once we’d done some excavating, we began setting our forms. The top of the form seen at left was set to align with the original deck’s level – but that old level is something I never trust: Many times, old decks were pitched to channel rainwater to one side or the other rather than to central drains. In this case, the decks were pitched downslope and everything was crooked, so we brought in a transit and shot new elevations.

We set our basic forms using the high standards I always apply, including two-by-four forming lumber and two-by-four kickers every 24 inches rather than the usual bender-board and one-by-three kickers. It costs a few hundred dollars extra to do it my way, but I see it as a cheap means of making certain everything stays square and at the proper elevations.

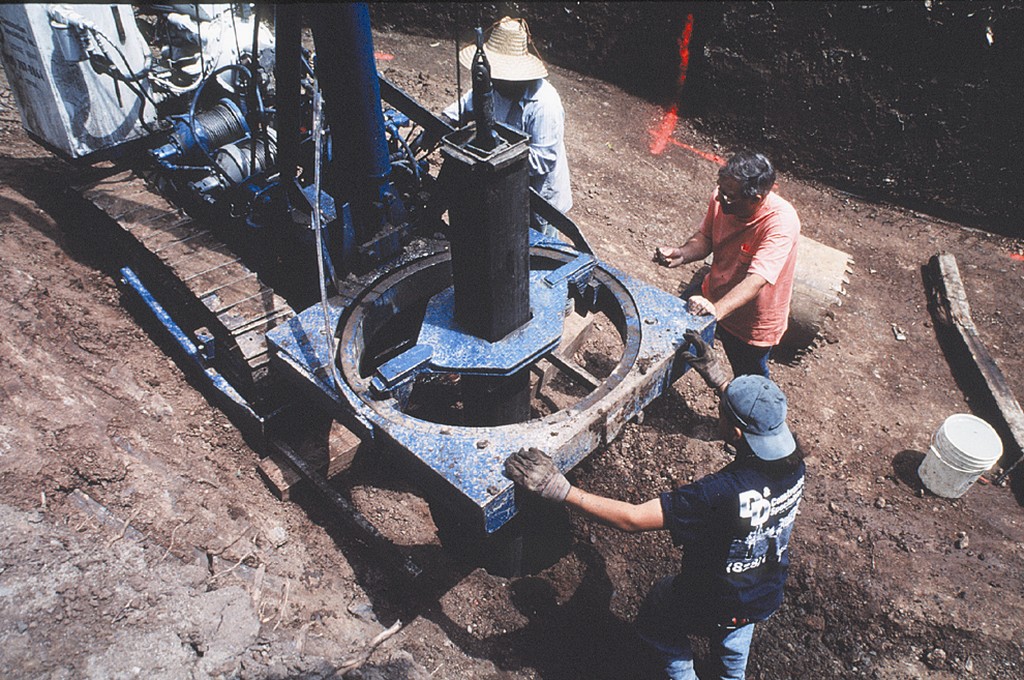

The soil we found beneath the pool was junk, as the soils report had led us to expect: Piles and grade beams would indeed be an absolute necessity. Once we knew the elevations, we marked the positions for the grade beams and five piles (seen at left) and began drilling (middle left), in some cases down to a depth of more than 50 feet.

We set the cages for the piles on site (middle right) – there just wasn’t room to do it any other way – and brought in a crane to reach over the house and move them into place when the time came (right). The cages consist of #7 rebar tied with loops of #3 rebar at six inches (note the spacers set like thorns along the structure to keep the cage centered in its hole). The piles would later be tied to the grade beams using #5 and #6 rebar as hooks and sleeves.

A Time to Change

While we were digging the piles, the customer decided she wanted something different. We took advantage of a spell of wet weather to meet and run through several rounds of perspective drawings.

Eventually, the revisions called for raising the deck and pool by two feet, creating space both horizontally to allow for an expansion of the deck area and vertically to clear space beneath the spa to accommodate the equipment room and some enhancements of the home remodeling.

Fortunately, we knew about this change in time to build temporary frames and add Sonotube collars to the holes to extend the piles by two feet (left). Big #6 bars were tied into the top of the pile cages to transfer the load of the grade beams.

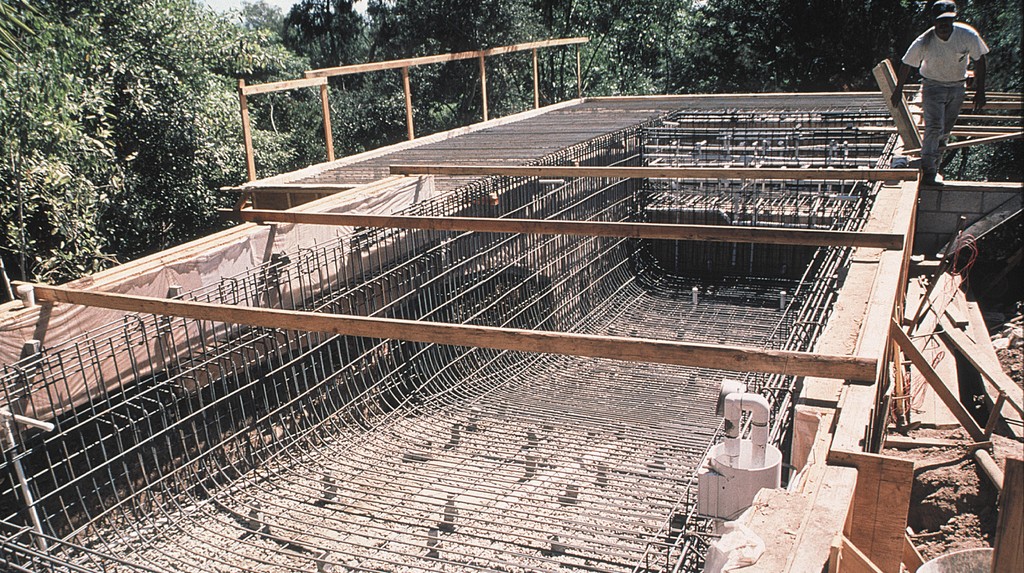

Once the piles were poured, we brought in a Bobcat to remove the spoils from the deep drilling and set the pool at its new height (middle) – now with a much larger portion hanging out in midair. This put some extra pressure on the forming crew to hold to tight tolerances – especially when it came to the cantilevered concrete deck that was to hang eight feet off the side of the pool – 12 inches thick next to the pool, 10 inches thick at the outer edge (right).

Next, we set drains and backfilled the floor of the pool using spoils from the original excavation. In this case, we could’ve used anything at all because the soil isn’t structural. In fact, all it does is act as a bottom form for the shell.

Nuts, Bolts and a Spa

Reforming the pool to the new specifications took a while, but once we were set, the crews arrived to place the plumbing and hang the steel (left).

My approach to plumbing and hydraulics didn’t just occur to me overnight. I’ve spent years learning what works and what effects can be created when it’s done the right way. And I give a lot of credit to my friend and Genesis 3 partner, Skip Phillips, who has taught me more about hydraulics in the past two years than I’d picked up elsewhere in the previous ten.

I also like to use a lot of steel. It may be called overbuilding, but I sleep easy knowing that the structure you see here will survive just about anything Mother Nature throws at it – something that can’t be said for many other pools in the area.

With so much steel at so many elevations, we had to install the plumbing in three or four stages. We’d lay some plumbing, stub out the lines, install more steel and then finish the plumbing. The work was particularly complicated in the 5-by-12-foot spa, which has 16 jets (right).

At this point, we installed an interesting joint detail between the pool and the non-structural deck on the house side of the pool. We used a V-shaped, accordion-style aluminum joint to act as a sort of channel to transmit water away from the pool while it also allowed for differential movement of the structures.

This notion of accommodating differential settlement is truly important: There’s a general lack of understanding that different structures with different footings made of different materials at different times and sitting on inconsistent soil will result in things moving independent of each other. When you build large, integrated structures such as this, it’s absolutely critical that you plan for this settlement and accommodate the situation with necessary joints in strategic locations.

What a Cantilever!

With the steel, plumbing and forms in place, we finally shot the pool, removing the rebound as we went: It has no place in my pools. (To save some time in stripping the forms, we’d lined them on the inside with plastic sheeting.) At this point, everything looked neatly on track (left), with the grade beams supporting the cantilevered structural deck telling quite a story on their own (middle).

That calm, however, did not last, because the owner had another change in store for us: The pool and deck slabs had both been shot when she asked us to extend the cantilevered decking on the far side of the pool along its full length. We had to do it without the advantage we had in setting up the original cantilever of tying everything directly to the grade beams. Instead, we had to work with the structure I’d set up to support the steps that originally were to sweep down the back of the pool to the lower level.

In this case, and in consultation with my structural engineer, I came up with a plan that used the existing steel I’d installed for use with the steps down to the lower level as the foundation for the new portion of cantilevered deck.

The steel for the steps had been set 24 inches below the beam, so we lapped the #5 bars, added 8-inch grouted blocks and set up a small wall (right). After backfilling the cavity between the pool’s wall and this new wall, we formed and poured the slab, setting up expansion joints to isolate the new section from the decking on grade.

Material Delights

Atop the cantilevered slabs, we hand-set bluestone shipped in from Vermont. I can’t say enough about this material: It comes at a high price, but it’s absolutely gorgeous.

To match the bluestone’s basic color, we poured the green concrete coping in place (left) and gave it a broomed finish. To prevent cracking, we set steel and concrete nails in the beam and tied them together with a heavy-gauge, wrapped, black-annealed wire. The emphasis as always was on structural strength: Rather than pumping the concrete from the street (which would have meant using more water in the mix), we went to the extra work of wheeling the concrete in and placing it in the forms by hand.

The tile we used for this project is also something special (middle left) – quite expensive, very elegant. We paved the way with several coats of sealant (tile is wonderfully waterproof, but you always get pinholes in the grout. We used quarter-rounds on every single edge and three-dimensional beaks at all corners. All of this is expensive, but the results are slick and beautiful.

The tile pattern at the waterline is another unusual touch (middle right). The projection of the triangles below the waterline is a neat visual idea – and when the pool was filled, those points seemed to dance on their own, as if they’re separate from the waterline tile. Quite an effect – although it did give the plasterers their share of headaches as they worked around them in applying my favorite green plaster mix (right).

Under Cover

One of the client’s principle desires was for an automatic cover, but as with so many other decisions about materials, she took her time in settling on a color.

We worked closely with Aquamatic Cover Systems of Gilroy, Calif., in generating a palette of colors for her review. After looking at a seemingly endless run of samples, we settled on a soft kelly green that ties in with the tile and plaster. Integrating the package, the leading edge of the cover and the stainless steel runners were all powder-coated the same green so they would basically disappear, rather than disrupting the aesthetics with a stainless-steel gleam.

Because the vaults for these covers are invisible much of the time, many builders I know don’t pay much attention to making them look great. That’s not my approach. In fact, the dam wall separating the vault from the pool is finished in tile, just like the rest of the pool, with no disruptions of the pattern at the water line (left).

The edges of the wall between the pool and the pool-cover vault, back and front, are finished in quarter-round tiles, too, just like the dam wall on the spa. Why set up the dam with an edge that might snag the cover? Finally, we used forms to make capstones for the vault using the same batch of concrete we used to pour the coping and applied the same brushed finish (middle).

What sets quality builders apart from the rest is how they handle the small things and work with their vendors to iron out all the details, as I did with Aquamatic’s Tom Dankel (right, on left side). The vault we set up for the automatic cover falls into this category – and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

David Tisherman is the principal in two design/construction firms: David Tisherman’s Visuals of Manhattan Beach, Calif., and Liquid Design of Cherry Hill, N.J. He can be reached at [email protected]. He is also an instructor for Artistic Resources & Training (ART); for information on ART’s classes, visit www.theartofwater.com.