Working at Water’s Edge

As watershapers, we all have one common goal in mind: We don’t ever want our concrete pools, spas, fountains or waterfeatures – whatever it is we’ve just finished building – to move at any time, in any way at all.

This is true no matter the physical or geological circumstances. On a slope, on the flat, elevated above a parking garage or set on rock or in sand or clay, wherever we’re working, we follow expert guidance that determines what we need to do to isolate our shells and decks from outside forces and protect them from anything and everything that might want to crack, tip or topple them. Up, down, sideways – we do what it takes to secure them against movement in any direction.

Of course, paying attention to this part of the overall package is a complicating factor none of us really like to face, but it’s almost inevitable when a project is located directly adjacent to a body of water: From tidal surges to subsurface water intrusion, from soil composition to storm scouring, there are no workable shortcuts here – and lots of opportunities to run into trouble.

To demonstrate what I mean, let’s look at five brief case studies – shoreline projects all influenced by regulations, by the site and by the client’s desires.

RULES OF THUMB

Before we begin, let’s do some necessary generalizing.

First, in coastal areas and near lakes or rivers, regulations are simply a fact of life. In our waterfront projects, for instance, we at Drakeley Pool Company (Bethlehem, Conn.) will deal with coastal commissions (every town seems to have one), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (far better known as FEMA), building inspectors, concerned citizens, overbearing neighbors and others whose essential interest seems to be preventing us from doing anything at all on site.

The process of passing through all of the required meetings, negotiations and plan reviews is abundantly burdensome: We’ve known it to take more than a year when endangered or even mildly threatened creatures are involved. However it goes, we accommodate the process simply by accepting that it takes time and that there’s little or nothing we can do to make it happen even a nanosecond sooner than it’s going to take.

The point we have on our side is that the regulators generally have to abide by precedent: If pools have been built elsewhere in the subject area at any point in the past, they are limited in what they can do beyond delaying a project’s start date. The resistance can be fierce, but typically it’s only a matter of time before we win plan approval.

Beyond access issues, of course, these sites commonly present us with slopes and saturated soil as well as storm and tidal surge levels we must consider. In addition, we must do all we can to deliver all of the advantages of living on the water, which means working with spectacular views and fitting in with the often dramatic architecture we encounter on these sites. Again, it’s not entirely unlike a cool, land-locked project, but it always seems that there’s a lot more at stake right on the water.

Third and finally, we’ve learned from experience that working on the waterfront should never be a limiting factor in a design or in meeting client desires. Location on a shoreline doesn’t alter the way we design: Mostly, it just affects the way we build.

In other words, in our role of translating a client’s ambition into a beautiful watershape, we’ve learned not to be dazzled or blinded by a waterfront property’s most obvious assets and challenges. Instead, we keep our usual focus on using a property’s virtues to deliver our clients as much pleasure and pride of ownership as we possibly can.

With all of this as context, let’s roll through five projects that show how different waterfront projects can be from one site to the next – but also how much they can have in common.

Private Club

Belle Haven, Conn.

This project involved removing and replacing an old pool and adding a shallow kiddie/wading pool to the site. The issues here were tidal surges and storm scouring, and the engineers called all the shots in defining the subsurface structure.

| Once the beams in the pool area were placed, cut to what turned out to be the wrong level and then capped, we added an extra mat of rebar to make up the difference in depth and made ready for shotcrete application. |

Given the immense weight of the filled pool structure, the movement-elimination approach involved insertion of 60 I-beams driven down to refusal – that is, the point where we reached stable material. The beams were then cut to length. (In this case, the level given to us by the general contractor was about seven inches lower than was actually required, so we had some additional work to do by adding a third mat of steel and thickening the pool floor.) Each steel pile was attached to the lower steel cage using #7 bars to mechanically tie the pool and supporting substrate together.

| The completed pool and splash pad are so secure the even severe erosion due to tidal or storm surges will have no effect on the stability or integrity of these watershapes. |

By the time we were done, these watershapes weren’t going anywhere. Even a storm surge so massive that it scoured all the soil away from the base of the pool would have no effect on its stability.

Residence

Milan, New York

This property is located inland on a large, manmade lake. I’d been called in to design a pool here previously, but the client decided to work with another contractor whose ideas about how to build the pool involved less money – and engineering and construction inferior enough that the pool soon failed.

| The original pool was a cracking mess when we ripped it out, but the soil beneath it was found to be stable enough – penned in between the home’s foundation and the seawall – that all we needed was a good dewatering system, an adequately compacted foundation and multiple hydrostatic relief valves to secure its future. |

The next time, I came to the site as an expert witness, then as a consultant on the replacement project and, finally, as the contractor. We broke out the old pool, doing what was required to clear and dewater the site while protecting both the home’s foundation and the seawall. Soils tests indicated that there was stable material just eight feet below the base of the pool, so we cleared away the bad fill the previous contractor had used and refilled the void with properly compacted material – no other piers or beams or keys required as determined by a geotechnical report initiated by our engineer.

| The new pool and spa are stable, beautiful – and fully isolated from any forces that might encourage either settlement or other structural stress. |

In the course of the project, we learned that water intrusion was a constant factor here, so we included multiple hydrostatic relief valves in the floor of the pool to keep it from moving in the event there was ever a power outage or some other failure of the dewatering system. Again, we did whatever it might take to keep the pool in place.

Residence

Westport, Conn.

When a neighboring property changed hands, it was discovered that our client’s old pool reached about two feet over the property line, so it was decided to remove it and replace it with a bigger pool and an in-pool spa – this time entirely contained within the lot lines!

The original pool had been there for years and had experienced only minor movement. Even so, we still called for a soil analysis; to make absolutely certain the new pool wouldn’t move, the engineer decided that a medium-duty pile system – more or less redundant – would be sufficient to lock the structure in place.

| Once the galvanized piles were driven in, trimmed and filled with concrete, we surrounded them with collars and added caps before using them to anchor the steel cage. |

Following his recommendations, we drove in four-inch-diameter galvanized piles in a grid pattern to a level at which they would all eventually be contained within the shotcrete floor. Once in place, we filled them with concrete, attached locking plates on top of each pile and placed sonotubes around the top four feet of each one. As the steel cage took shape, we tied each locking plate into the structure and made ready for shotcrete application.

Placing the equipment at the proper level was a big issue here – as it is in lots of FEMA-managed areas. The basic requirement is for all electrical systems to be placed high enough above the pool’s water level to meet the FEMA-defined storm-surge elevation – a placement that would have seriously impinged on pump performance in this case.

| The small pool is a thing of beauty and isn’t going anywhere. The split-level equipment pad is a bit less visually appealing, but it was all the room we had to work with in meeting both the pool’s needs and FEMA’s requirements. |

Fortunately, FEMA’s rules mandate this placement only “when practical,” which gave us the leeway we needed to put our pumps where they needed to be to function properly. The resulting split-level pad is crowded and ungainly, but the pumps are set at the pool’s water level, so we have no concerns about losing prime and possibly burning out pumps and melting pipes.

Residence

Fairfield, Conn.

One of the key challenges in watershaping projects along crowded shorelines can be access: This was the last house out on a point, and the pathways on either side of the home were so narrow that even getting wheelbarrows through just wasn’t possible. Mooring a big barge in front of the property wasn’t a possibility, either, so we collectively decided to jack up the home to give us the access we needed.

| The home had a failed pool and no effective access, so the decision was made to lift it out of the way. To prevent future problems, we secured the new work in place with big wooden piles. |

This was another case in which we’d been tasked with replacing a pool that had failed. Our soils report indicated the need for a heavy-duty level of support for the pool and associated structures including a large, separate spa and a surge tank to take care of a vanishing edge. The solution here involved driving in telephone-pole-size, pressure treated piles down to the refusal level. Once trimmed, we bolted stainless steel pile caps onto these posts for attachment to our steel cages.

| The new pool and spa complement the home in ways the old pool never did – a complete package made possible by massive intervention. |

Wood always seems an unlikely material for such an application, but once in place, they exist in a very low oxygen environment and will not rot. This means isolating the substructure from the possibility of scouring away material and exposing the wood to air. That was determined not to be an issue this far back from tidal surges. So once again, we used the approach that most effectively and efficiently locked our structures in place.

Residence

Greenwich, Conn.

This project is still under construction at this writing, but it’s here anyway because it’s a great reminder that there are no limits to what can be done with waterfront-pool designs. It’s also of interest because we didn’t need to do anything specific to lock things in place – no piers, no beams, not even a key.

| Although the shell required no extra support, we took great care in placing and properly compacting its gravel base and making ready for special features including a floating cover. |

The 18-by-50-foot vessel has an extra-large shallow lounging area, a floating cover (made by Grando of Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and acrylic wall panels (from Hammerhead International of Las Vegas, Nev.). The pool has a vanishing edge; the raised spa has a full-perimeter overflow system trimmed out in glass tile (from Bisazza of Milan, Italy). It’s about as full-featured as a pool and spa can get – with gorgeous materials – and it’ll be spectacular right there at the water’s edge.

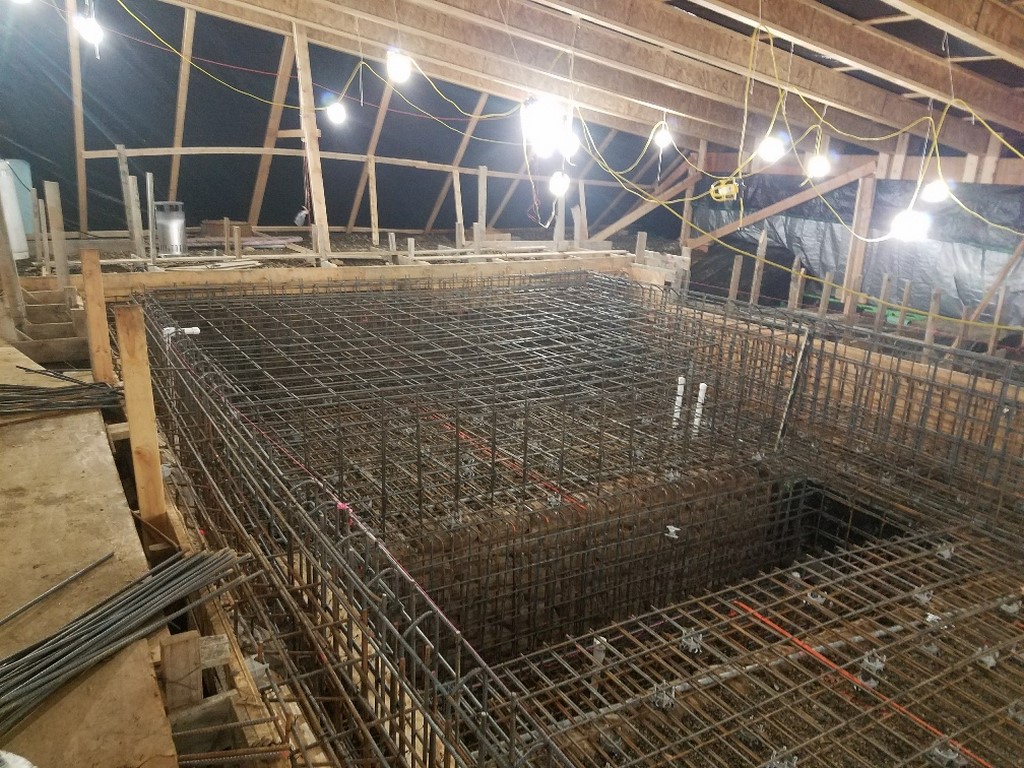

| We upped the steel scheduled by a good bit to ensure that the shell would, once shotcrete was applied, constitute a monolithic, unmovable mass. Later, we did some additional steel fabrication to make ready for insertion of several acrylic panels. |

As for keeping it in place, it sits on compacted stone and was deliberately over-engineered with respect to the steel schedule (we used a good 30 tons of steel alone!) and heavy masses of shotcerete applied to multiple mats of rebar – including five in the shallow lounging area. The thought behind this alternative approach to locking our work in place is simple: With so much mass and so much steel, the structure will never crack. So with a properly engineered, properly compacted stone foundation, it really won’t have anywhere to go!

William Drakeley is principal and owner of Drakeley Industries and Drakeley Pool Company in Bethlehem, Conn. He holds the distinction of being the first and only pool builder to sit as a voting member of the American Concrete Institute’s Committee 506 – Shotcrete and serves as secretary of the ACI C660 Nozzleman Certification Task Group. Drakeley is also an approved examiner for ACI-Certified Nozzlemen on behalf of the American Shotcrete Association (ASA), chairman of the ACI Pool Shotcrete Subcommittee, an ASA technical adviser and deputy director of the Genesis Educational Program. He teaches courses on shotcrete applications at the Genesis Construction School, World of Concrete and numerous other trade shows and is a contributor to Shotcrete Magazine and other industry publications.