The Power of Flowers

Long a fixture in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, the Conservatory of Flowers is one of the most photographed structures in a city famous for picturesque beauty.

At 125 years old, the facility is the oldest surviving public conservatory in the western hemisphere. Originally built in 1878 and then rebuilt after a devastating fire in 1883, it’s also an architectural and engineering treasure – an extremely rare example of a prefabricated Victorian-era structure that had withstood the test of time. In 1995, however, a severe storm caused extensive damage and led city building officials to deem it unsafe for public use.

Despite that decision, a dedicated group of paid staff and volunteers doggedly maintained and managed the site and its plants in a gallant effort to stave off further degradation, all with the hope that someday the Conservatory would be restored. They bit off no small challenge, as many of the facility’s “botanical residents” are difficult and expensive to maintain – including a 100-year-old Philodendron with five-foot tall leaves that fills much of the space beneath the Conservatory’s towering central glass dome.

The ongoing campaign to save the facility picked up steam in 1998, when the World Monuments Fund placed the Conservatory of Flowers on its list of the “100 Most Endangered World Monuments.” With that exposure, funding snapped into place and, by 2000, renovation had begun in earnest – including planning for what was to be our work in creating a new aquatic-plants exhibit for the building’s east wing.

NATURAL SELECTION

Designed by Portico Group of Seattle, the aquatic-plant exhibit was intended to recreate the feel and experience of a tropical rainforest, complete with colorful (and even some carnivorous) plants and flowers. The watershape was to play a central role in conjuring that exotic experience for generations to come.

| The Conservatory of Flowers in Golden Gate Park has long been one of San Francisco’s most-photographed structures. A lengthy, complicated renovation project has revived the facility with the aim of delighting future generations of park visitors. (All photos by John Ramos) |

In February 2002, we at Aquatic Environments met with Conservatory staff to establish our capabilities with respect to installing the exhibit and meeting its ongoing maintenance requirements. This was far and away the most prestigious project we’d ever pursued in our company’s brief history (we had been around just three-and-a-half years at that time), but collectively we had decades of experience in the restoration and management of natural and man-made lakes, ponds, streams and other waterways and had a strong case to make.

After several more meetings, we were finally successful in securing the design/build contract and immediately jumped into the planning stage. Up to that point, the watershape was simply a set of plans with architectural renderings, detail views and a rough mechanical schematic. This left us to seek input from the project’s major players and develop a design that would meet the needs of the facility and plants while staying within budget.

|

A Glass Span The aquatic-plant exhibit described in the accompanying article includes an unusual glass bridge that enables visitors to get closer-than-usual looks at some of the exhibit’s exotic plants. It also performs an aesthetic service by masking the division of the lower pool into two parts by a large, cast-acrylic panel. Although building the bridge was beyond the scope of our contract, its inclusion had a lot to do with the way we built the three interconnected pools the bridge was to span. We had to factor it into our load-bearing calculations and our design drawings while making arrangements for conduits to power an unspecified lighting system. All in all, it added considerably to our work – but the outcome made it worthwhile. — G.F. |

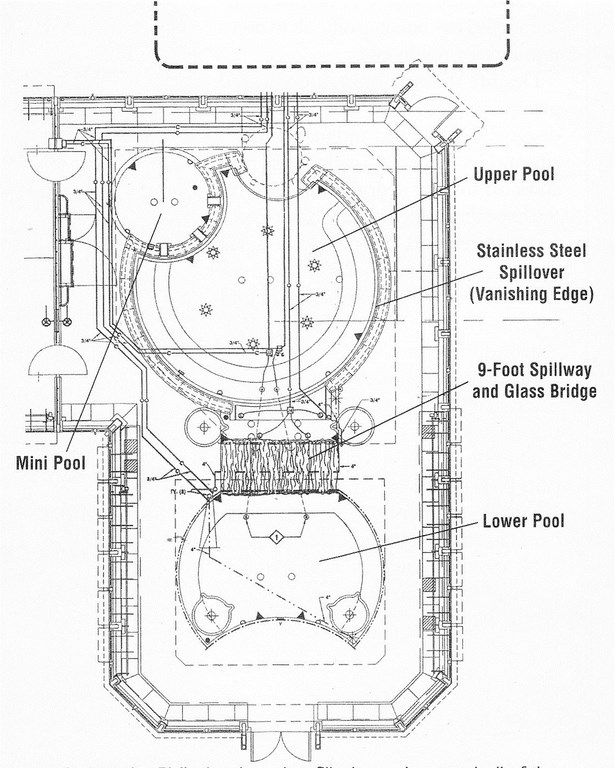

The result of this process was a set of working drawings for a watershape consisting of three visually integrated vessels: an upper pool, a second-tier mini-pool and a lower pool, each designed to house different sets of plants. With a long service life in mind, the whole complex was to be made of reinforced gunite as a monolithic unit.

As planned, the circular upper pool was to be 30 feet across and spill over a long vanishing edge into either the mini-pool – a horseshoe-shaped catch basin ten feet across, or spill over a sheer, nine-foot edge into the catch pool. The lower pool, 22 feet across, is separated from the catch pool by a large acrylic barrier. Four “spilling pots” would accent the flow into the lower catch pools, with two pots on the deck and the other two appearing as though they were flowing on the lower pool’s surface.

The vessels were to range between 18 and 42 inches in depth and house hundreds of spectacular tropical plants growing in pots set directly on the midnight blue, two-part epoxy finish chosen for the vessels’ interiors. Elegant materials were selected to set off the watershape’s clean, simple lines: A beautiful, powder-coated stainless steel band, for instance, was chosen to serve as the weir for the 75 total feet of vanishing edge, and we specified fiberoptic lighting and laminar jets as well. (The project also features an artificial tree and a glass bridge described, respectively, in sidebars just above — ‘A Glass Span’ — and below — ‘Tree Housed.’)

STAYING FOCUSED

As a small player in a huge project with a $25 million overall budget and an extraordinarily high profile, we were realistically worried about getting lost in the shuffle. But that proved not to be the case, and we soon came to see that our part of the east wing was to house some of the Conservatory’s most exotic and prized specimens and was intended to be among the facility’s biggest draws.

|

Tree Housed The artificial tree that looms so prominently above our watershape was another design element that stood beyond the scope of our contract – and was another case where we had to work creatively and interactively with another contractor to make certain everything would come together. The tree could not be installed until pool was nearly finished, with all its capstones in place – but had to be brought in before the vessels were filled because there was a significant amount of work that needed to be done from inside the pools as installation moved forward and we continued our finishing work around the tree. Coordination was a huge challenge, but we managed it despite all the starting and stopping. At “tree time,” the upper and lower pools were nearly complete. With finishes in place, anchoring points were drilled and scaffolding erected both inside and outside the vessels. As each operation was completed, we waterproofed the intrusions and did our touch-up work – a discontinuous workflow that gave us all headaches but that resulted in successful installation and detailing of the exhibit’s signature feature. — G.F. |

Plants now on display include floating lilies and other familiar water plants, along with vibrantly hued bromeliads, fascinating carnivorous plants and other tropical species that require warm temperatures, high humidity and bright light. The star attractions are several Victorian Lilies, giants that grow floating pads upwards of six feet in diameter and protect themselves with thousands of needle-sharp thorns.

The construction of the watershape seen on these pages strongly resembles that of a common swimming pool, but the complex is anything but ordinary when it comes to operation, circulation and maintenance. Two separate circulation systems operate the trio of vessels, each of which is specifically designed to support a distinct array of plants – and each of which, absent any chemical control, functions at temperatures that invite extreme algae growth and raise a range of other water-quality concerns.

But thoughts of the Conservatory’s history, the project’s mission and the specifics of maintenance were far off in the distance as construction began. In fact, our work on site began with a disheartening thud as we surveyed a sand pile enclosed by a rough concrete footing – a mess that made it tough to envision the layout and finished project, let alone pin down exact positions for the structures and a plumbing system that had to be routed under the old foundations to an as-yet-undetermined location.

| The Conservatory’s plants include many specimens of great size and age, including the Philodendron that fills the main entry hall of the facility with its five-foot-tall leaves. |

Left with few fixed items from which to pull reference points, we found that simply laying things out was a daunting exercise. We knew, for example, that the watershape had to be centered perfectly inside a room that had been completely dismantled and set up under a fixed beam that did not yet exist. And naturally, we had to have the pools and decks in place before any of that structure could reappear. Just as naturally, stub ups for items such as the four-foot diameter spilling pots had to be set within fractions of inches – this at a point where flow characteristics were still being modeled and equipment had yet to be selected.

We muttered a bit about chickens and eggs as we worked, but we had to keep moving forward just the same.

MAKING DECISIONS

Suffice it to say that we spent days rather than hours laying out this project, and even then we were aware that we making little more than educated guesses about where everything should go when it came to the three vessels, their plumbing and their equipment.

| Views across the water surfaces from a variety of angles showcase a wide variety of exotic aquatic plants, including the giant lilies that seem an irresistible draw to the Conservatory’s visitors. |

We eventually took a deep collective breath, completed the layout phase and began setting up the structural footings, plumbing and electrical conduits. Even with a painstakingly developed layout, however, this phase was made difficult by the sand in which we worked. It was like building a sand castle, with gravity working against us at every turn and making our excavations unstable and prone to collapse even though we were digging to depths that weren’t even deep enough to raise OSHA concerns. By the time we were through, we’d had to invent a specialized trench-shoring system to make subsequent construction possible.

The rough grade was at minus-12 inches, which wasn’t much of a challenge, but the bottom of the building’s structural footings checked in at minus-54 inches and we had to reach two feet below that level to allow adequate access for the plumbing runs and conduits – all of which ran to an equipment room whose rough location behind the east wing had been set with no design or details as yet.

| There isn’t much by way of elevation changes, but we made the most of the space by varying the ways water flowed through the system, using perimeter overflows, vanishing edges, sheet waterfalls, spillways and flows from the decorative pots to define different areas within the relatively small available space. |

The tricky excavation was followed by steel and plumbing phases complicated by the fact that roughly two dozen different trades were now on site performing a wide array of duties right on top of each other. Interaction and timing of the work became important factors in the critical path toward completion, and there was no hope of separating the work of our watershapers from the activities of the woodworkers, masons and glaziers who were operating on the same tight timetables. Throughout, I’d say there were no fewer than three distinct trades operating at any given time – all in a space of just 365 by 65 feet.

Through all of this difficulty in the early going, we managed to toil our way through and establish locations for the structures and piping runs in such a way that the pools could be constructed as a solid unit that we could shoot in one very long day. We did so in the belief that, given the soil conditions, one integrated watershape would have better long-term structural integrity than would three individual pools set up with cold joints.

DESIGNS AND CHANGES

As mentioned above, we became involved in the project at a time when the watershape was only slightly more than a “rough” with respect to functional design. This lack of hydraulic and mechanical design definition brought on an ongoing need for request-for-clarification (RFC) submittals; time spent waiting for responses; and eventually responding to the “as bid” or “change order” determinations handed down by the project’s managers.

|

The Equipment Set Interestingly, the equipment used for the watershape in San Francisco’s Conservatory of Flowers is something of a cross-section of products available in the swimming pool and pond industries, with each component selected for very specific performance characteristics. The pumps, for example, were selected from three different suppliers based on variable sets of criteria that taught us that one size definitely does not fit all. By contrast, the two biofilters were packaged units sold by a single distributor. The other equipment – the filters, pre-filters and UV system – were sized and selected once the gallonage of the entire system was determined. Wherever possible, we selected units that would not only meet but would reliably exceed their specified warranties with the goal in mind of minimizing replacement and forcing anyone to deal with the marginal access we were able to provide to the equipment. Ultimately, we settled on Pentair’s MiniMax heater as well as some of its pumps and backwash valves on an equipment pad that also featured Jandy’s valves, filters and pumps. OASE Pumps donated a laminar jet system, and we used a Hayward Maxi-Flo pump to drive it. Fiberstars provided the illumination for the nine-foot sheet waterfall from Custom Cascades, which also provided the three mini-pool spillways. Because of the unique nature of the project, we did as much as we could to select just the right equipment but ended up in some cases making educated guesses about how certain components would operate under the conditions we envisioned. Fortunately, everything came together at start-up, at which point a few adjustments were all that was needed to fine-tune the systems. — G.F. |

Included in this time-consuming process were our professional views of how an item or function should be considered or constructed, based on our experience. The result was an ongoing, laborious, complicated process of revising and changing throughout the duration of the project, all covered by weekly or monthly visits from the architect.

In all of the give and take, deliberations about flow and water-exchange rates were the most critical. As a decorative display, the hydraulics would not have been particularly difficult to arrange. But the fact that this was to be a living biological system as well as a display multiplied our challenges exponentially.

Ultimately, we devised a system that uses multiple pumps and achieves a turnover rate of just two hours – a swiftness that was needed to ensure water quality and clarity in the absence of any chemical treatment. We also set it up so there would be minimal draw-down at system initiation, the concern being that a consistent water level is necessary for the health of the plants.

| The tree may be artificial and working with it through the installation process was no small task, but it makes an enormous contribution to the tropical atmosphere of the space and interacts beautifully with the watershapes on many levels. |

So many details of the project fell into the “to be determined” category that we had to make educated guesses about penetrations and their size to accommodate such things as the yet-to-be-designed lighting system for the bridge. Simply placing the equipment was a big issue as well: The Conservatory had no space to spare, yet we were setting up a system that included five pumps, two biofilters, two pre-filters, two heaters, two UV sterilizers, three control panels and a cartridge filter (for the laminar jet system). This was exclusive of all the piping, valves and fittings that would make the three pools operate as intended.

The equipment space initially offered was about the size of a small half-bathroom. Simply put, there wasn’t nearly enough room for our equipment (see the sidebar just above for details) as well as the 50-gallon water heater needed for the staff’s shower. After careful negotiation, however, space was found for a two-tiered equipment room that meets code and allows for reasonable service access.

PERSONAL PRIDE

As watershapers, we leave our personal touch on each project we design or build. As specialists who engage in custom, one-of-a-kind projects such as this one, we know further that what we do is most often undertaken without the sorts of benchmarks or routines that might make it easier to project costs, timetables and action plans.

|

The Acrylic Panel One of the more prominent (and difficult) elements to design and install for the Conservatory project was the curved acrylic panel situated in the upper pool. Intended to provide for underwater viewing, the four-by-eight-foot panel gives the upper portion of the exhibit an aquarium-like feel, was great from an aesthetic standpoint and serves its purpose – but was a design element to which nobody paid much attention until fairly late in the process. Nobody, for example, had thought through the engineering far enough to determine the force with which the water would press against the panel, which was to be supported only on three sides with no support up top. Nor had anyone considered the fact that aesthetics called for freeboard between the waterline and the top of the panel to be less than an inch – all of which meant the panel’s size and thickness as well as the dimensions of a mounting notch in the shell had to be calculated within fractions of millimeters. But everything eventually came together. The panel was custom-manufactured by Nippura, a Japanese firm that specializes in large cast-acrylic panels such as this one. Nippura’s U.S. representative pitched in, and along with our project manager, David Jones, worked out the sizing and engineering. During construction of the shell, we built a Masonite mold to create a notch that would accept a flexible seal, specialized sealants and the panel itself. Some of us lost a bit of sleep in the days before we installed the panel, aware that the load could result in deflection of the panel that might force it out of the notch and also conscious of the fact that a whole lot of guesswork had gone into the execution of this part of the project. To be sure, we breathed a collective sigh of relief when the watershape was filled and the panel worked perfectly. However stressful this episode with the acrylic panel may have been, it stands as a wonderful example of how different materials can be integrated into watershapes to create a certain ambiance or just the right aesthetics. — G.F. |

Yes, it would be easier to work on similar sorts of projects and develop the efficiencies that come with repetition, but what appeals to us most about what we do is the uniqueness that sets each project apart and keeps us fully engaged in the work we do.

Beyond that, as a fourth-generation Californian, I see something special in the Conservatory of Flowers project – a sense of history that came with the structure, a special sense of place that came in working in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge and the sense of camaraderie that came from working shoulder to shoulder with so many talented and professional craftspeople on the job site.

Certainly, we take pride in having participated in such a high-profile project, but in retrospect we don’t see prestige as having been our prime motivator. Instead, we stood back when we were finished, in awe of the building and its history and happy with thoughts of the smiles of joy and wonder that will be brought to future generations of our fellow Californians and visitors from around the world.

It’s a feeling of pride and satisfaction that can’t quite be accurately described.

George Forni is president of Aquatic Environments, an Alamo,Calif.-based design, installation and service firm specializing in lakes, ponds and other large waterfeatures. He started his career in the waste- and reclaimed-water industry in the mid 1980s. Before long, he became project manager for an aquatic service firm, for which he managed a number of projects in conjunction with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as well as in other regulatory agency-controlled jobs. His company now focuses mostly on the needs of large commercial clients in the Western United States.