Dressed for Success

A glance at our portfolio of dozens of golf-course projects dating back to 1990 shows that no two of them are exactly alike – despite the fact that our mission in each case has been exactly the same: It’s our goal with every project to leave behind grassy patches that have seemingly been draped across natural terrain that has been there, untouched and untrammeled, since time immemorial.

In other words, we’ve crafted elevation changes, watercourses, plantings and other defining features so carefully that it seems like folks who enjoy chasing little white, dimpled balls came along and have done little more than plant fairways and greens atop contours provided for them by Mother Nature.

In one case at least, the actual situation stuck quite close to that ideal: Our marching orders at Shady Canyon Golf Club in Irvine, Calif., were to do as much as possible not to interfere with a state-protected natural environment. As was reported in WaterShapes in 2006 (click here), getting it done was no easy task – but the results are outstanding.

By comparison, our approach to the Donglim Golf Club in Chuncheon-fi-Gangwan-do, South Korea, was the exact opposite of what we did in Shady Canyon: I can’t think of an instance where we’ve been anywhere near as intrusive as we were here, but I’m also convinced that the outcome is effectively the same: The results are so seamless, so elegant, that there’s no way to tell how extensive our work was on site and no sign at all that we did anything more than add fairways and greens to “natural” terrain.

WATER WONDERS

Last time, we noted that this project involved cutting the top off a mountain and redistributing the spoils across the adjacent canyon (click here). This was a task competently executed by local contractors, and we admired but never envied their confrontation with the mass scale of the work or the amount of soil and rock they had to break out, rearrange, supplement and compact per our design/construction documents.

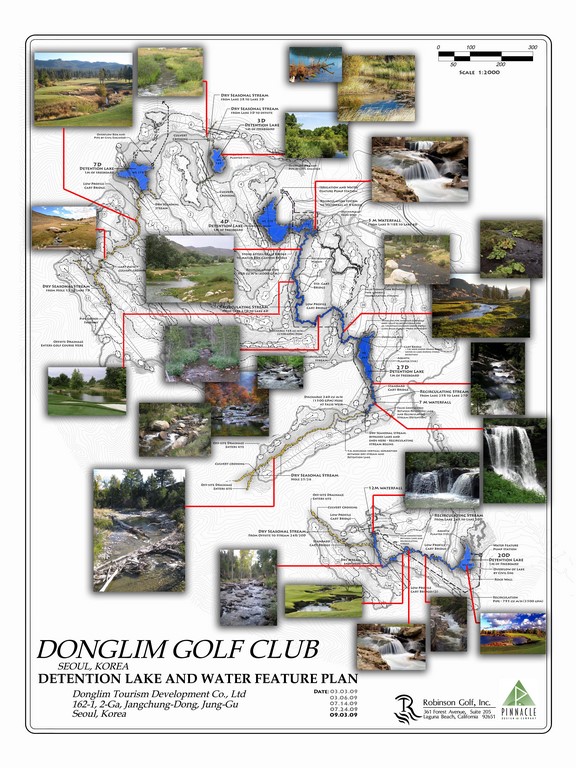

And all of it had to be done without disrupting the natural flow of an existing stream that ran the length of the canyon: This watercourse was vital to the welfare of a number of downstream farms, and as mentioned before, we quickly learned that environmental regulations in South Korea are approximately as stringent as they are in coastal areas of California.

We did have to alter the natural streambed to integrate it into the new contours, of course, inserting lakes for visual interest but, beyond that, offering no interference to the natural volume of flow. Designing and installing this detention system was perhaps the most environmentally sensitive of all the tasks we pursued on site.

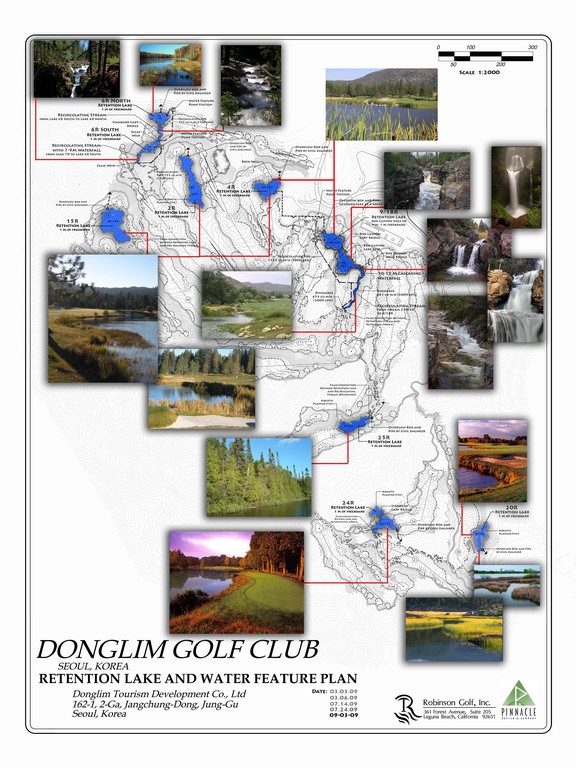

| These illustrated maps of the site show the intimate space shared by the golf course’s two huge water systems – one designed to speed water through the property to farmland farther down the canyon (left), the other meant to hold water on site for irrigation and recirculation from the bottom of the course back up to the top (right). These detention and retention systems are fully separated under a strict environmental agreement, but they weave across the course together as though they form one meandering, entirely natural water system. |

By contrast, the retention system we engineered to control irrigation water and keep the sprawling, 27-hole course’s purely artificial waterways in operation was far more extensive and required deployment of multiple pumping and recirculation stations to move water collected at the base of the course back up to the top. Given the fact that this system would handle direct runoff from the amply fertilized fairways and greens, we knew the key was to keep water moving actively from top to bottom: Agitation and aeration were our best allies in keeping the water crystal clear.

With these coexisting systems, the goal was always to keep them separate physically while entirely integrating them visually. In one area, this meant creating a bypass for the natural stream where it ran close to the back edge of one of the retention ponds. The illusion works so well that there’s no doubt in the mind of the average visitor that the natural stream flows into a natural lake at one end and flows out at the other.

| The ponds at Donglim Golf Club come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, but what they all have in common is that they come into play on the course and are a key part of the overall, naturalistic impression the setting makes on any golfer lucky enough to garner an invitation to play. It’s hard to strip away the manicured fairways and greens from the visual context, but if you focus on the details, the ponds themselves all seem as though they’ve been there, undisturbed, for thousands of years – an impression enhanced by our replanting of so many of the site’s own trees. (All photos throughout by Joann Dost, Monterey, Calif.) |

In addition, all aspects of these water systems had to be over-engineered to deal with the possibility of a drenching, hundred-year storm event as well as annual monsoon seasons in which it’s possible for eight to 16 inches of rain to fall in a day: The two systems had to stay separate no matter how much water was introduced, which explains why our planning and permitting processes for these watercourses took a full 18 months.

As we also learned, water is expensive in South Korea, so we placed a lot of emphasis on recycling and reuse on the retention side of the system. Essentially, the compiled lakes and streams operate with a quick turnover cycle that keeps water moving, aerated and clear. Better yet, so much of it is recirculated that new municipal feed water does little more than replace evaporative losses.

Finally, throughout the site, we began setting liners topped by chicken wire and then packed with concrete topped by gravel, rubble and stones of various sizes. We did this knowing that potentially huge flows could easily strip away anything that wasn’t rigidly fixed in place. In addition, this is a golf course for club members of average skills: We know well enough that spiked footwear and exposed liners don’t mix!

SHAPING THE LAND

With the water systems approved and under development, we began focusing on course details and aesthetics and the process of making everything we did seem as though it had been there forever.

As mentioned previously, there’s always improvisation in landscape architecture at this scale – and that was certainly true with Donglim Golf Club. Making it work took constant contact between our staff and the course architect, Ted Robinson, Jr., as well as with the conglomerate’s design team, including the chairman who was the driving force behind the project.

These sessions could involve a great deal of give and take, but almost without exception, we were able to settle any conflicts and keep pursuing the vision that had been established at the start. Of course, this meant those of us who represented Pinnacle Design (Palm Desert, Calif.) had to be on site for numerous visits – I was there about 40 times myself – for regular consultations in support of our project manager, who stayed on site most of the time throughout the two-year construction process.

| The course’s 13 lakes are connected to one another by waterways of all descriptions, from calm, gently rolling flows to riotous cascades and waterfalls. Here we paid particular attention to what we found when we arrived on site and examined the original waterways; we also explored natural streams and watercourses in nearby canyons in formulating and varying our approaches. |

As the finished contouring moved forward, our thoughts turned to the 11,000 established trees we’d removed from the site in preparation for excavation. They’d been stored nearby through two brutal winters, and we were figuring that we’d be lucky if 30 percent of them survived replanting.

As it turned out, however, nearly 98 percent of them have re-established themselves successfully: It was thrilling to watch them green up the first spring after they were replanted – and testimony to the value of working with trees fully acclimated to the site and its microclimates: We know that if we’d clear-cut them and brought in new trees from somewhere else, the attrition rate would have been considerably higher.

We also had fun with various bridges that appear around the property. The ones near the clubhouse are magnificently detailed, with tight fits of stone materials and impressively formal looks. As you move away from that civilized core and get out into nature, however, the appearance of the bridges gradually changes – getting a bit more rustic and informal as you move deeper into the course.

Then there was the chairman’s desire to include modern artwork throughout the site: He’d been so impressed by the way we’d incorporated Frederick Remington-inspired statuary at The Quarry in southern California that he wanted to do something similar here – but unique, too. In this case, he commissioned nine colorful “dragon balls” for placement around the course to pay homage to an old Korean folktale: Good luck flows to those who spot all of them as they pass through the grounds.

| Although exquisite naturalism was our goal in setting the stage for the property’s fairways and greens, this was definitely a space that would be used by the golf club’s members – meaning we had to make navigating around the course both safe and relatively easy. We set up cart and walking paths to meander through the space like dry streambeds, but we also worked to highlight the clubhouse’s low-slung but still-lofty architecture and incorporate artworks hand-selected by the club’s chairman. |

We also noted a distinctive, international flavor in the overall program: The course architect and landscape architects came from the United States; the clubhouse was designed by an architect from the Netherlands, and various sculptures (beyond the dragon balls, which were fabricated in South Korea) came from an international cast of artists.

Placement of these art pieces was of special importance to Chairman Lee. We’d propose our ideas; he’d make the decisions. In one case, for example, we’d figured on placing a dragon ball in a partially obscured site to add a challenge to hunting for them. That wasn’t the point, he explained, and persuaded us to relocate it to a more accessible spot.

QUITE THE SITE

In all, we included 13 lakes on the property, nine of them part of the retention system, four of them associated with the natural stream and the detention system. The detention system is driven by snowmelt and highland rainfall, so there are times during the year when its flow slows down considerably. By contrast, the retention system is fed by two huge tanks that introduce municipal water for irrigation.

By keeping these systems entirely separate, we fulfilled our commitment to downstream farmers that nothing we’d do would interfere with either the volume or quality of the water they received. This consideration made us focus so thoroughly on capture and reuse in our artificial waterways that the resulting recirculation systems are amazingly efficient.

We like to think that this conservation-oriented strategy is transferable: In a place where people love golf and there’s no choice but to build new courses on land that’s basically unusable for any other purpose, the approach we took points in a strong, positive, efficient and thoroughly neighborly direction.

Since our work on site was completed and the course opened in 2011, it has steadily been rising in world rankings: It’s now in the Top 100 for clubs and is currently ranked as the 118th best course in the world – just what the chairman ordered.

Ken Alperstein is co-founder of Pinnacle Design, a golf-course architecture firm with offices in Palm Desert, Calif. He is a 30-year veteran of the landscape design industry and has specialized in golf course landscaping since 1989. The company’s portfolio includes high-end championship golf courses, clubhouses and grounds throughout the world – including several courses rated in the top 100 in the United States by Golf Digest and Golf magazines. He may be reached at [email protected].