Images in Time

As designers and builders, we might feel with every new project that we have created the most profoundly original setting in the world.

In most cases, however, our most likely achievement has to do with adapting an architectural concept developed long ago, putting a modern twist on it and calling it our own. For me, in fact, the more I learn about the history of watershaping, the more I feel connected to ancient watershapers and recognize that we haven’t created anything really “new” in a long time.

We all know clients, for instance, who want their backyards or public spaces to look like Spanish or Italian villas, French or English formal gardens, or maybe peaceful Japanese-style Zen gardens. The question isn’t about where we and our customers go for ideas; instead, it’s about how we, as designers and builders, can best fulfill these demands and pull the projects off with an underlying sense of quality.

In my case, I look to the best examples of the past and use them to inform and inspire my work. Indeed, there are invaluable resources available to us all in the annals of watershaping, and the following pages provide just a glimpse at what’s available. Here and in articles to follow, we will meander through the columns of the Parthenon, travel across the Islamic world and conclude by looking at how some of our watershaping colleagues have benefited from using architectural precedents in their modern-day projects.

Greco-Roman Foundations

Thousands of years ago in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, smart, observant people devised systems for directing water to where it was needed by using pipes and aqueducts. These early systems watered the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and helped to irrigate and control flooding in the fields along the banks of the Nile.

Early hydraulic engineers discovered something interesting: Pressure was produced in a pipe with increased height of water – a single principle that stands behind every pool, bath and waterfeature built until the modern development of mechanical pumps. Indeed, this initial spark of insight is responsible for thousands of years’ worth of pools, baths and fountains across the ancient world.

The ways in which designers used this hydraulic principle tended to change right along with the social needs and architectural styles of their cultures. The Greeks and Romans, for example, created vast bathing pools as well as recreational swimming pools using a sense of proportion and shape familiar to us from structures like the Parthenon in Athens, built in what we know as the Classical style (see the image at top right below).

The Olympia Pool, built in 500 BC, was a 16-by 24-meter vessel set outside the Temple of Zeus at Olympia using construction techniques that would be familiar to any modern contractor. The Greeks also built the 10.6-meter-wide Baths at Delphi as part of a large gymnasium complex. (This facility was subsequently remodeled by the Romans to include hot water piped from local volcanic springs.)

Greek and Roman conquerors carried their cultures’ sense of style from the mountains of India to all of Western Europe and North Africa. In modern Turkey at Ephesus, for example, exists a Greco-Roman swimming pool that may be the oldest that still holds water (middle left). Water usage here wasn’t limited to recreation: Ephesus is also home to the oldest known restroom (middle right) – a 24-seat affair with an aqueduct-fed flushing system!

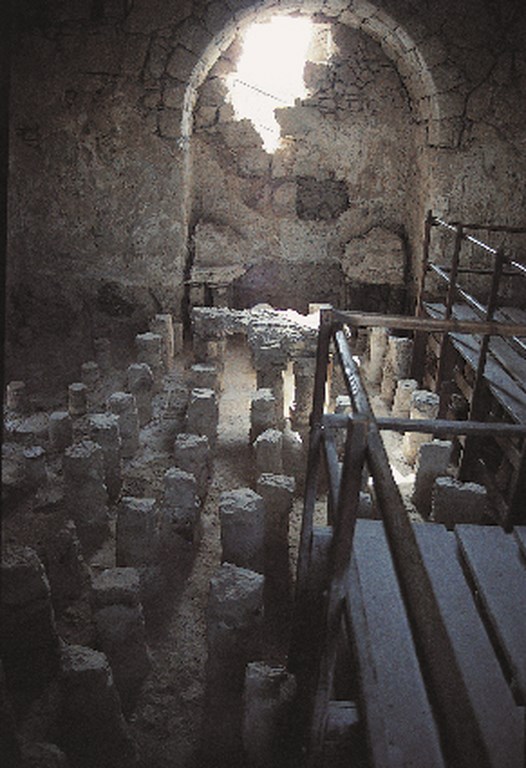

Farther south in ancient Palestine (modern Israel), Masada is home to some of the oldest extant public baths – created under irregular and unfortunate circumstances.

The people of the area had been forced to this high plateau by a Roman siege that lasted more than 60 years. Cut off from food and ordinary supply lines, they made do with available resources and built plaster-lined baths that still hold water nearly 2000 years later (right). They also channeled hot water under wooden floorboards that were supported on limestone pillars, creating what may have been the world’s first saunas (lower left). Although at war with the Romans, builders at Masada were nonetheless clearly influenced by Greco-Roman styles, technology and materials of construction.

The wealth of the Roman Empire ultimately gave rise to great extravagance in architecture and to expressions of personal power. The Emperor Hadrian’s Villa is an amazing example: Around 100 AD, he started construction of this “royal getaway” to ease the stresses of exercising absolute power. The country refuge featured a 1,500-foot hippodrome (a sort of flat racing stadium) bordered by long porticos (an architectural theme we’ll see again on page 34 with Hearst Castle’s Neptune Pool). His Maritime Theatre – a miniature version of a citadel complete with reduced-scale buildings – served as the emperor’s private playground.

Amid all the excess, Hadrian commissioned spectacular waterfeatures and effects, all in classic Greco-Roman style except for the famous Canopus, which depicted Hadrian’s voyages to Alexandria and shows flashes of an older Egyptian style – right down to the crocodile statues.

Islamic Influences

The Islamic culture of the Middle East played an invaluable (if less recognized) role in the history of watershaping by contributing to a refinement of hydraulics – advances that were used throughout Europe during the Renaissance and in our own pools today. This hydraulic knowledge, intertwined with Islamic architectural style, spread both east and west from Persia from the 7th Century onward – toward two very different regions that came to have remarkably similar and influential design styles.

Heading westward, the Moors came to dominate North Africa and eventually crossed the Straits of Gilbraltar to control much of Spain for more than 600 years. Islam also headed east, venturing into India and influencing its culture and architecture for a far longer period that culminated in the 17th Century with the Mughal Gardens and the Taj Mahal.

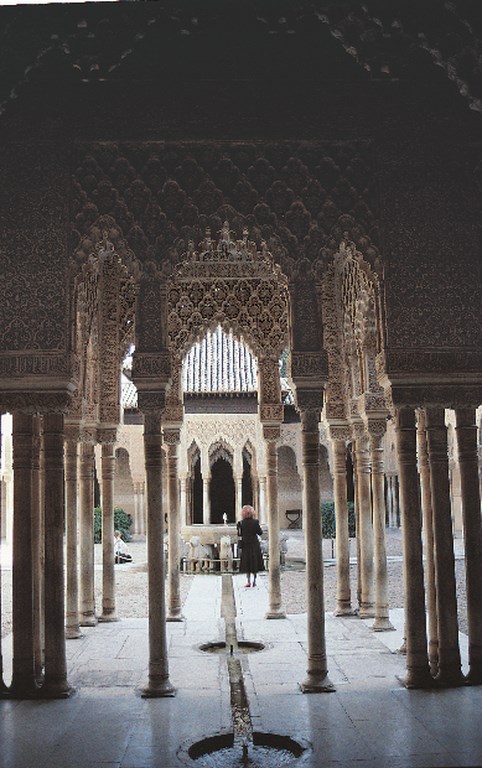

• In Spain, the Moors took the design ideas left behind by Greco-Roman culture and extended them with the elegant archways and quatrefoils that highlight Middle-Eastern styles. At the Alhambra (“red castle”), the Moors created a bold, forceful environment featuring the Court of the Lions, where rigid geometric forms dominated each scene for aesthetic as well as religious and spiritual purposes (top left).

• In Spain, the Moors took the design ideas left behind by Greco-Roman culture and extended them with the elegant archways and quatrefoils that highlight Middle-Eastern styles. At the Alhambra (“red castle”), the Moors created a bold, forceful environment featuring the Court of the Lions, where rigid geometric forms dominated each scene for aesthetic as well as religious and spiritual purposes (top left).

This hilltop castle is an amazing feat of hydraulic engineering – a knowledge later picked up by European masters who applied its principles to designing the great waterfeatures of Renaissance Italy and France, from the fountains of Rome to the gardens at Versailles. Here and elsewhere, the Moors took the rigidity of Greco-Roman design and created human-scale, comfortable settings that nevertheless displayed their complete mastery of materials and monumental design (middle left).

|

The Water Thing Why do we feel compelled to manipulate water? The answer takes us in two directions, one spiritual, the other very practical. Water was once seen as a divine essence that flowed from the heavens and brought with it the gifts of the gods. The Nile, Tigris and Euphrates were all sacred rivers that inspired our ancestors and anchored their existence. It’s not surprising that early cultures used water in tribute to their beliefs and saw intimate connections between water and their gods. Even today, with all our knowledge of the water cycle and water’s role in nature, we still apply sacred values to water. We know how precious it is, from irrigation systems to its use as a catalyst in the production of cement. It is an elemental force – a compound we use to facilitate most everything we do. Water is truly amazing stuff: • It can move with gravity or defy it – falling as rain or rising through evaporation – M.H. |

Generalife, the summer villa of the lord of the Alhambra, is home to the Court of the Canal, which is where we clearly see the link between Moorish/Spanish and Islamic/Indian watershapes.

What we see is the shared notion of threading water through many different spaces using long, thin pools set off with small spouts along their length (middle right). The water thus serves as an axis that separates the garden into quadrants. (This breaking into fours is a prominent theme in Islamic/Moorish architecture.)

We also see this axial arrangement at another Moorish site: the Alcazar in Cordoba, Spain (right). Here, the designers have incorporated what has since become a common watershaping theme – the placid pool lined by graceful jets of water – that finds a recent echo in the gardens of the new J. Paul Getty Museum in the hills above Los Angeles (see below).

• In India at Agra, the Taj Mahal takes basic concepts seen in Moorish Spain, but elevates them to a much higher plane and far grander scale. Few people in the west know that the Taj Mahal is actually a tomb, a beautiful memorial to lost love surrounded by the Mughal Gardens near the Jama River. Using advanced hydraulic techniques, designers channeled that river to power waterfeatures in much the same way Moorish designers put water pressure to work at the Alhambra and the Alcazar.

To achieve various water effects, engineers created large holding tanks that feed an intricate network of pipes and spray heads. The reflective qualities of these long basins accent the immense size of the Taj Mahal, and the waterways themselves serve to channel visitors along pathways that set pools, structures and gardens in the most favorable perspectives (bottom left).

This monumental use of water and patterned use of architecture and spaces stands in contrast to the sensibilities of the Greeks and Romans. Where the Greeks saw water as a way to announce and celebrate the presence of their deities, designers of Spain and India used it in a more utilitarian way to define space and guide perception.

Contemporary Echoes

Today’s watershapers clearly work with a stylistic vocabulary created for us by hundreds and even thousands of years of architectural and technological trends, and you don’t have to look very hard to find 20th-century examples of work that harks back to ancient precedents.

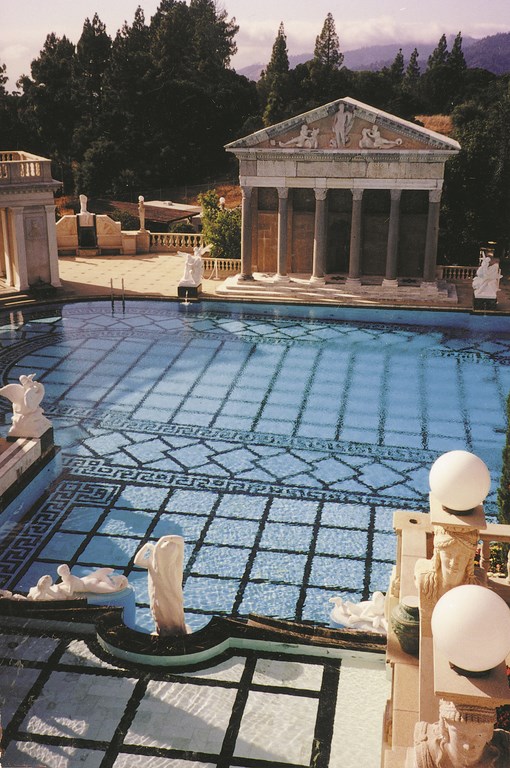

Built by architect and engineer Julia Morgan at San Simeon, Calif., over an extended period early in this century, Hearst Castle is home to two significant swimming pools and a variety of important waterfeatures. The Greco-Roman Neptune Pool is probably the most memorable swimming pool of the first half of this century and feeds on design principles used by the Greeks, from the perfectly proportioned marble and granite columns and temple details to the statuary surrounding the pool and its elegant tile patterns (top left).

William Randolph Hearst was an art collector who picked up much of his treasure trove on buying binges across Europe. The Neptune Pool evolved through the years from fountain to pool and changed dimensions a couple of times along the way, but every step was rooted in Greco-Roman principles he recognized and his designer was able to deliver.

The Hearst estate also included a huge indoor pool, finished entirely in Venetian glass tile (middle left), some of which was made with flakes of 24-carat gold that now shimmer through the water. Here and elsewhere on the grounds, you see the influence of Spanish/Moorish design as well as echoes of French Renaissance styles borrowed from Versailles. The estate is open to the public and should be the object of a pilgrimage by every watershape designer.

The Hearst estate also included a huge indoor pool, finished entirely in Venetian glass tile (middle left), some of which was made with flakes of 24-carat gold that now shimmer through the water. Here and elsewhere on the grounds, you see the influence of Spanish/Moorish design as well as echoes of French Renaissance styles borrowed from Versailles. The estate is open to the public and should be the object of a pilgrimage by every watershape designer.

Down the coast at the Getty Museum, designers were challenged to bridge the gap between the 1990s modernist buildings on the hilltop site over Los Angeles and the Getty’s collection of Greek and Roman antiquities. In this case, and in keeping with the Spanish traditions of Southern California, the inspiration comes straight from the Alhambra and the Alcazar (middle right). The look here is far from antique; rather, it’s a warm, engaging reinterpretation of traditional themes of aquatic design.

|

Working the Legacy How can we improve today’s watershapes? I have a simple suggestion: Trust the creators of the past. These designers, engineers, architects and builders have collectively spent hundreds, even thousands of years working and studying and transferring their skills to future generations, and we as modern watershapers have all this heritage of knowledge on hand to use as we see fit. Exploiting that knowledge doesn’t take much effort. Countless books document the history of design and architecture – and a great many of them are about places and the projects of people who should be part of your own knowledge. You can also go right to the source and actually go see these places. Photographs like the ones you see in the accompanying article are a big help, but there’s no substitute for drinking in the sounds and smells and total settings that characterize the best work of past watershapers. I can’t overstress the value of the architectural styles, concepts and forms left us by builders of the past. If we are to progress beyond the limits of our own immediate surroundings, then we as conscientious creators need to stop pretending that pool building began in the 1920s and that our work represents the highest evolution of the craft. In fact, we represent just a small space on the watershape time line, and we’ll have much more to accomplish if we work as part of this tradition rather than outside it. With all that we have available to us in terms of inspiration and technology, we can take watershaping farther than our ancestors ever dreamed. We are the new architects of water, and we have much to do and accomplish. – M.H. |

Another contemporary expression of antique styles is the pool complex at the Bellagio Hotel, which opened in Las Vegas in 1998. Intended to mimic a grand villa at Lake Como in Italy, the 27 million gallons woven in and around the hotel bring a slice of Italian countryside to the Nevada desert (right). This American gambling town has been known for cartoon-like architecture, but this re-creation brings a sense of class to an otherwise gaudy city. There are no $1 hot dogs here: All aspects of the hotel and its pools are at the highest level of design (bottom left).

The water complex contains 11 major pools and fountains. A long linear colonnade reminiscent of the portico at Hadrian’s Villa stretches through the space and provides a measure of diversity while separating the two major swimming pools.

The distinction here is one of the designer’s perspective: These aren’t pools with waterfeatures; rather, these are waterfeatures in which it is possible to swim. In fact, this drama is particularly effective without swimmers, as you work your way past watershape after watershape inspired by Italian models. With bathers in the water, it becomes a playful swimming environment that elevates everyone’s perception of all a swimming pool can be.

We invite you to write or e-mail us with your suggestions of watershapes you’d like to see covered as part of this series of articles. Our goal in conducting this research is simple: We want to provide all of us with the kind of knowledge we all need to improve the art and craft of watershaping.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at [email protected].