The Show Begins

Each custom design project is, of course, different from any other. The client may be a known quantity, but the site and the budget won’t be and, as professionals, we always end up responding to unique sets of variables with eyes wide open.

In the first part of this series, we looked at the disembodied details and components that made up one of these unique design packages. Starting with this part and continuing into the next, we’ll examine at what was involved in assembling that particular set of features and, in this article, look specifically at how my collaboration with the client proceeded from initial contact to acceptance of a preliminary design.

Obviously, what I’ll describe here is my own approach to the design-development phase – but this is not a prescriptive exercise: I know that what works for me might bear only the slightest resemblance to what works for other designers at this stage of a project, and I’m definitely not here to preach. Instead, my purpose is to pull the process apart in an analytical way, shedding a bit of light on what’s involved in design development and leaving you free to assess, respond and react as you see fit.

So let’s dig in, starting with my first meeting with this client and how I began to assemble the information I needed to pull his specific project together.

STARTING THE CONVERSATION

Many designers I know include at least the start of a formal information-gathering process in their initial client meetings, but instead I do what I can to keep these first encounters free and easy and informal – as though we’re old friends enjoying a fun and lively conversation.

As this exchange unfolds, I’m gathering impressions and assessing how well we at Lorax Design Group (Overland Park, Kans.) fit with a client. Nothing too specific is covered here, in other words – just a general background chat that will help us get to know each other well enough to make decisions about moving forward.

With this particular client, the initial meeting took place in my offices (not my usual practice as I prefer to be on site to gain an immediate sense of the available space) and lasted about an hour. Our time together gave me the opportunity to eyeball the client and see how he responded to questions, how he expressed ideas and how he interacted with others. Basically, I needed to know if he met my expectations, and often these first meetings – a sort of litmus test – are all it takes for me to decide the fit is no good and that I should walk away.

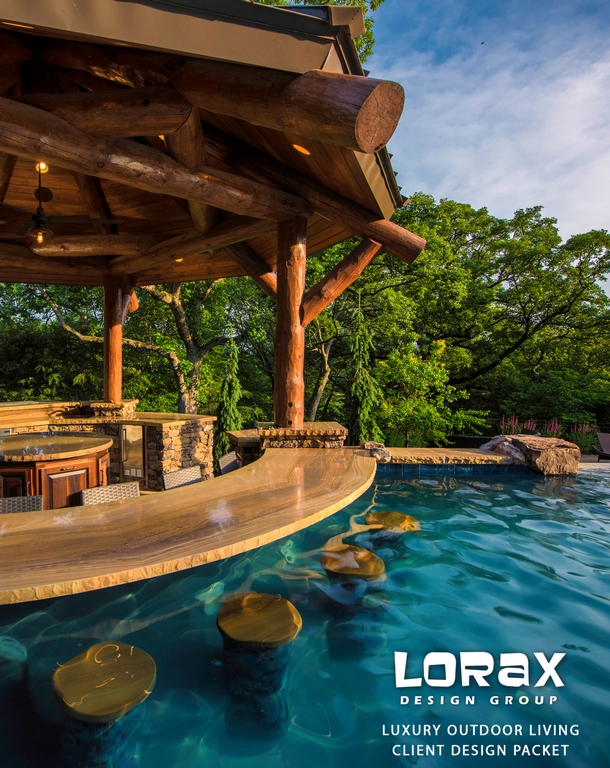

| Figure 1: The cover of the Client Packet is meant to inspire – and get clients thinking about grander backyard environments along with their dream pools. |

But here, there was promise that something good would emerge from further contact. He obviously brought a lot of ideas with him, but he also seemed prepared to let me channel them along lines I thought would be productive. So once we were done, I sent him what we call our “Client Packet” and asked him to take his time in digesting the information and thinking through his responses. Once it came back to me and I had a chance for my own review of the data, I said, we could sit down together to talk about specifics.

Quite often, clients will not complete the questionnaire in full, preferring instead to talk things through in fluid, organic ways rather than spell anything out so deliberately. But others like to work this way and enjoy the sense of a structured information exchange, so we include the survey in every prospect packet and suggest strongly that it should be reviewed carefully – even if they never put pen to page – so it forms a foundation for future discussions. It also documents the intended depth of our preliminary discussions and helps us avoid any sense down the line that we haven’t covered all the bases.

Starting with inspiration, the questionnaire has a dramatic photo of one of our favorite projects as its first page and continues with a pair of sheets listing client and architect references to back up our reputation as a credible player in the regional marketplace (Figure 1, above). With each of the listed past clients, we define the scope of our work (such as “landscape master plan + swimming pool”) to demonstrate the range of services we provide.

|

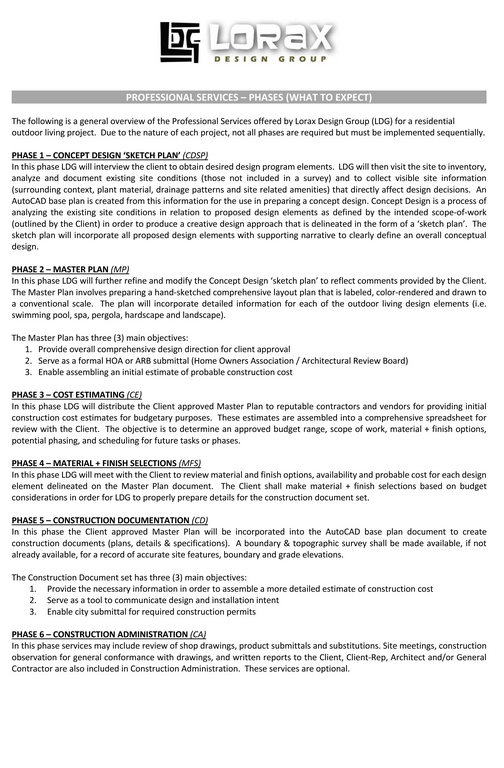

Figure 2: This sheet outlines the relationship between clients and our operation in complete detail, from the design phase all the way through to construction if that’s how the relationship develops. |

Next (as seen in Figure 2 above) comes a page headed “Professional Services – Phases (What to Expect).” In brief paragraphs, we define six project stages (concept design/sketch plan; master plan; cost estimation; material and finish selections; construction documentation; and construction administration), with only the last one indicated as optional.

The next three sheets are what we call a “needs assessment form” that asks for detailed contact information before eliciting general information on the site (the portion of the property we’ll be designing, client-recognized drainage or soils issues, what to protect by way of trees or structures) and, for example, whether there’s an interest in screening out undesirable views or enhancing desirable ones (see selections as Figures 3 & 4 below).

We also seek information not just on the style of the home, but on the client’s personal preferences when it comes to colors, plant types and such details as whether attracting wildlife is desired. We ask about family, pets, social gatherings and intended uses as well as outdoor cooking/dining preferences and storage needs. Are there special play areas in mind? How about fire features, shade structures or outdoor sound systems?

Then we move along to the pool, asking about shape, size, style, features and amenities. If the client wants a spa, we ask for input about size, shape and seating as well as whether it’ll stand alone or will be integrated with the pool. We ask about lighting along with some practical questions about where the electrical-service panel is located relative to the work area and what is known about utilities and where the lines run.

REVVING THE ENGINE

This brief content summary of the client packet only skims the surface: As the sample pages shown here demonstrate, the document covers dozens of specific areas of inquiry. Moreover, the need for information is constantly evolving, so the form we sent to this particular client more than a year ago is quite different from what we’re sending out today. Why so? Because the way people think about their outdoor spaces changes so rapidly these days that we’ve seen the need to be flexible just to keep up!

But no matter the specifics, there’s a lot to the questionnaire, and the level of information this client provided definitely helped us on our way. It’s an exercise that can take hours to complete, which is why I prefer making it a “homework” assignment rather than sitting in front of anyone asking all these questions from printed sheets!

At this point, because we’d met for the first time at my offices rather than at the site, I’d seen nothing more of his backyard than I could glean from Google Earth’s aerial and street views and hadn’t really begun to engage my “design engine.” So I had to wait until our second meeting, which became much more of a design consultation than what usually happens the first time I see a site.

In this case, being there with him worked out well, giving me an opportunity to respond immediately to his questions as we walked around and I quietly assessed grading, drainage, access, views, existing vegetation, exposure to sunlight and shade, lighting possibilities and – very important – positive or negative issues related to neighboring properties.

| Figures 3 & 4: These are extracts from the questionnaire portion of the packet and go into great detail. Note that we get to the pool only after defining a broader perspective on the outdoor setting. |

As I get older and wiser, I focus more and more on these early encounters, never letting my desire to win a contract get in the way of deciding whether it makes any sense for us to tackle the project in the first place. Along the way, I look for a certain willingness of spirit in our clients: There’s no fun to be had in working with folks who want to circumvent our basic processes!

So in essence, these early sessions are something akin to a honeymoon, with everyone enjoying the relationship as we move through design discussions and reach the necessary agreements about the project’s direction. At this point, everything may be preliminary, but there’s hard work already being done as we test the strength of the working relationship.

Again, there were no red flags with this client. But if I’d had misgivings at this point, even after investing in multiple design meetings and follow-up conversations, I would have let him know that we were not going to carry things past the documentation phase. And he’d been prepared for this eventuality with the client packet, which, as mentioned above, indicates that actual construction by us is an option – both for him and for us!

Age and wisdom have also had another effect on the way I approach these early meetings. It used to be that I would sit down with anyone at any time, but that’s no longer the case. We can meet at any point between 7 am and 3 pm now, Monday through Friday only – times during which I don’t interfere with their family time and they don’t impinge on mine – and again, all of these follow-up meetings take place at our offices rather than on site. There are certain exceptions, of course, but for the most part this is a policy our clients are willing to accept.

SEEING CLEARLY

As the on-site meeting progressed, I was seeing the site itself and had the chance to ask him about lifestyle, extended family, immediate family, intended use of the space and the extent of that use – holidays mostly, summers only or year-round?

Years ago, I would have taken lots of photographs and a few measurements to get a sense of the terrain to carry forward, but I don’t do that anymore because I know I’ll be sending out members of my staff to gather highly detailed information about the site. So instead I focused here on absorbing basic impressions from the client and the site and started processing more and more raw data as we walked around.

It’s at this point that I decide whether to ask for soils and geotechnical reports before we get too deeply involved in the design process. Sometimes, if we’ve done work in the immediate area or if it’s a new home for which such information has already been compiled, we can skip this step for now. But I’ll still ask if rock was hit in excavation, gather information about drainage and ask about runoff from other properties.

As for basic reports, I want them – without exception. Sometimes the home builder already has the information, which is great. And other times, homeowners will ask to forego the expense of testing until they’ve seen a design. (In that case, they have to agree beforehand to indulge my need for test results before we generate a final budget and construction documents.) At a minimum, however, we always require a new site survey at an early point in the process to make certain we’ll be placing our proposed work within the boundaries of any setbacks or easements.

The contract spells all of this out in great detail, including our requirements for architectural plans and elevations, a plot plan and boundary/topographic surveys, geotechnical reports, grading and drainage plans, hydrological plans for water supply and discharge and details on utility/service connections. We also get formal clearance to take photographs and develop three-dimensional site or building models.

At this point, I asked the client to provide me with any information he had about predetermined choices related to materials, finishes, furnishings or lighting systems; transmit any inspirational images he’d found through magazines, Houzz or Pinterest; indicate his landscape and irrigation plans; and provide me with an anticipated project budget.

All of this led up to a clutch of important exercises related to siting the pool. Personally, I follow the deductive approach championed by Ian McHarg in his 1969 book, Design with Nature. He suggests looking first at important things that cannot be changed and then allowing the rest of the site to tell you what needs to happen. It all fits well with my personal conviction that I always have two clients: a homeowner and the site.

In short, I opened myself to experience this particular site in all of its uniqueness. From the outset, I considered how everything would work together, from traffic patterns, views, landscape features, slopes, destinations, plantings, trees and flower beds to patio areas, outdoor kitchens, pools, spas, waterfeatures and other features we’d discussed so far.

The site immediately helps by telling me what it requires by way of grading/drainage and circulation: If those two needs aren’t satisfied, I know nothing will work: A site that doesn’t drain properly or a site that is not easy to navigate will not function! I could develop a whole program that would meet every single one of the client’s multiple desires, but if I missed the fundamentals of good design, he wouldn’t be happy with the results – nor would I.

PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER

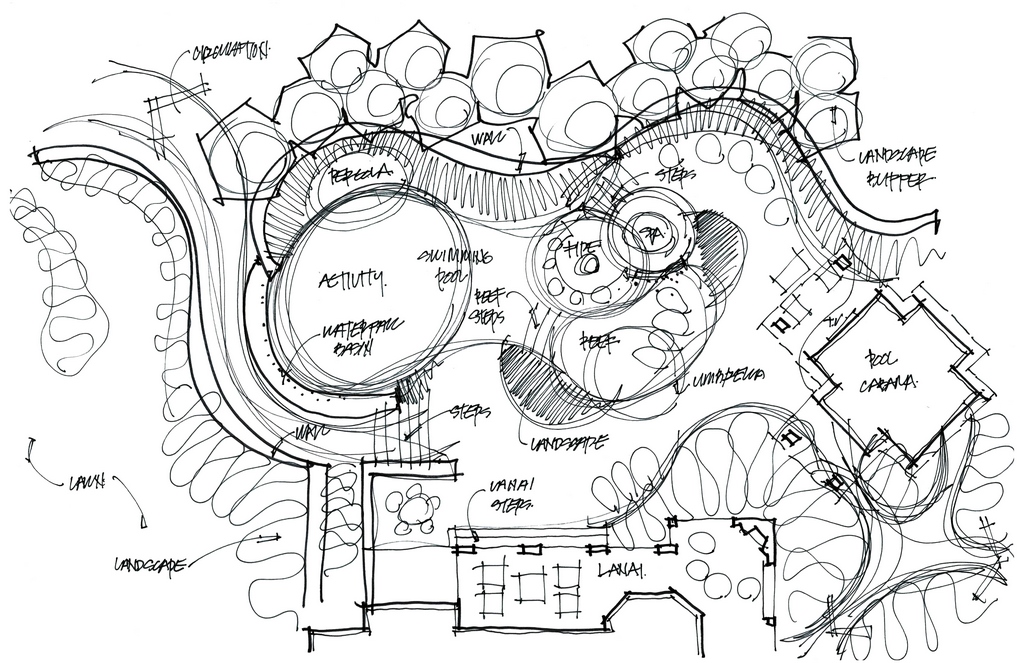

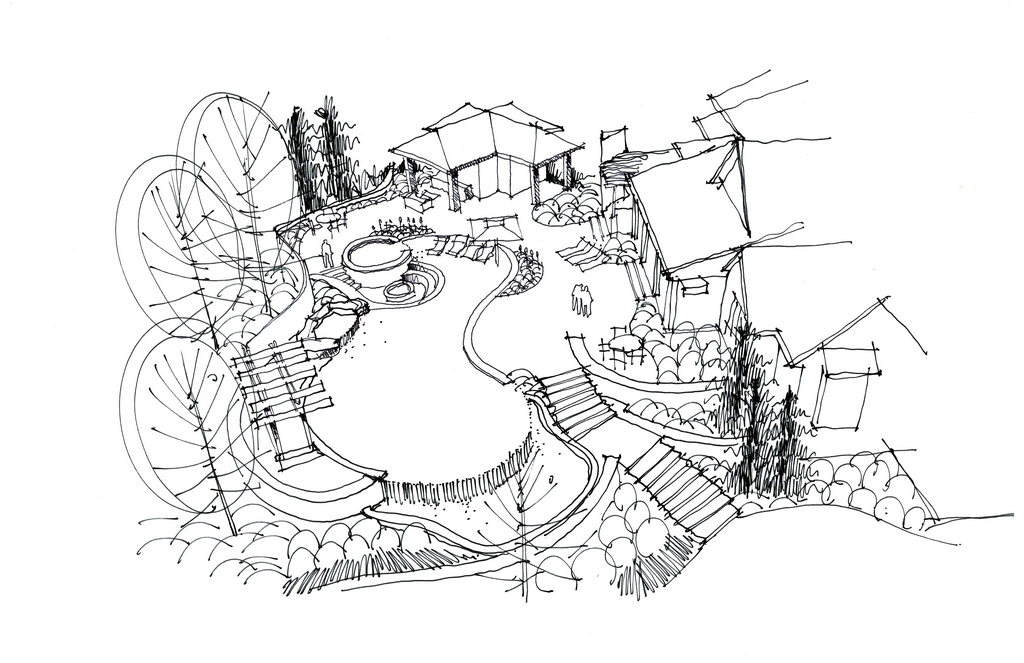

By the time our on-site meeting ended, I knew that the design would include a pool, a spa, large deck areas, a shade structure, a pool house, an outdoor kitchen, a vanishing edge and a fire pit, all organized to follow the yard’s slope (as sketched out in Figure 5 below). The space would also have extensive landscaping, including a dry streambed, planting beds, pathways, new trees and an outdoor sound system. I also knew there was more to come by way of personalizing details as the plan populated itself.

To me, design is all about listening and learning before I do any applying. So when I’d heard his ideas and recognized that some of them didn’t align with our defined processes, I was able to step in to communicate ideas that addressed these issues in detail. He understood for the most part and came around, but I knew if he was adamant at this stage about a bad idea and I couldn’t really make it work, I could still walk away and pass the project on to another designer who might be more pliable.

In that sense, the idea-generation process is like a gigantic sieve: It starts with all sorts of big-picture ideas, weird ambitions and quirky visions of how things should go, but eventually a lot of the problematic features get caught on the screen and we’re able to narrow the possibilities down to those that eluded capture. Now all that remains is draping appropriate features, materials, finishes and furnishings across the site to make the design work, visually and functionally.

| Early meetings and conversations with this client led to multiple sketches of varying levels of detail that enabled us to work with him in refining the design. Once we were on the same page with these drafts, it was time to formalize the design and begin preparing a master plan. |

Sometimes a client will go along with the process and will sign a contract that will lead us to prepare documentation and even get ready to begin our construction work on site. And sometimes old ideas we’d set aside will resurface, or all-new ideas will come to mind and discussions will begin again.

Sometimes, as with the intrusive little walls this client wanted to include on what I’d set up as a nice, open slope leading down from the house, I’ll give in and do the work. In others, as with the waterfall feature he wanted to include at the water’s edge (still there in the sketch shown above as Figure 6 – and a detail that left its traces behind through the inclusion of an extra skimmer), we were finally able to edit the design and get rid of a detail I never really liked.

It’s not often that my clients involve me in this sort of back and forth. Typically, the project we’ve agreed to will unfold smoothly from the concept phase onward and we’ll move through to project documentation without a hitch. There may be some further discussion about finishes or specific materials, but these negotiations seldom rise to a point where there’s any issue we can’t settle.

But I get ahead of myself: Before we come anywhere close to starting with construction, there are other aspects of the modern design-development process we must consider, including the presentation and what goes into taking a working design and turning it into models, a master plan and, finally, construction documents.

Kurt Kraisinger is a landscape architect with more than 25 years’ experience in design and consulting. In 2009, he founded Lorax Design Group with a goal of creating memorable spaces that allow people to engage in their surroundings. He received his degree in landscape architecture and urban planning from Kansas State University and participates in Genesis programs. He may be reached at [email protected].