Heritage Trails

The renovation and restoration of historic watershapes and their surroundings is a rather peculiar specialty. After all, such projects don’t come along very often and never amount to enough to be considered a primary business focus.

Even so, whenever and wherever they present themselves, those who get involved must always be ready to meet sets of very specific and often unusual challenges.

The fact that these sites are historic, for instance, means that they also tend to be old, so they almost invariably come with surprises with respect to how they were originally built, what sort of remodeling and repair work has been done through the years, how they’ve been maintained and, often, the degree to which they’ve suffered from neglect or even abuse. Original plans can be hard to come by, so from the start there’s a need for a good bit of educated guesswork and a fair measure of improvisation.

On top of that, you also have to be prepared to deal with members of any number of community organizations and historical societies ( not to mention concerned citizens, donors and benefactors) – all of whom have something to say about the need for absolute authenticity. Many times, for example, they will insist on reusing original materials or, where that’s not possible, fabricating appropriately genuine replacements. They’ll also require that you work in such a way that you stay within the watershape’s original footprint without damaging or otherwise compromising historic surroundings or precious nearby structures.

All of this means that the process can take many times the span of a normal project – in my experience, sometimes more than a decade. Through it all, you must be patient and accommodating, ready at the drop of a hat to respond creatively to tricky issues and, perhaps above all, willing to compromise along the way.

DOING OUR BEST

As complex and frustrating as these projects can be, we at Rowley International (Palos Verdes Estates, Calif.) enjoy them immensely because they give us the opportunity to step directly into the flow and history of these facilities in a way few professionals ever manage to do. We learn about the cultural and emotional importance of these places, hear the idiosyncratic stories and translate all of that into strategies that revive these facilities and enable them to continue adding to the cultural richness of our communities – and society as a whole.

We’ve had the honor through the years of working on a range of watershaping projects that can, to varying degrees, be labeled “historic.” Our goal is always to restore the beauty of the site while bringing systems and structures up to contemporary standards. In some cases, that means light, mainly aesthetic renovations; in others, it results in complete reconstruction of new structures with “original” appearances. For the most part, however, these projects will land somewhere between those extremes.

We’ve also found that determining exactly what makes a place “historic” is open to interpretation. In the projects discussed in detail here, for example, two are manifestly historic in nature: the Annenberg Community Beach Club in Santa Monica, Calif., which was designed and built by Julia Morgan; and, a short distance away near downtown Los Angeles, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House.

The third, which has to do with the Palos Verdes Beach & Athletic Club, may lack the provenance and renown of the other two, but the community has adopted the facility as a local cultural landmark and sees it as the historic embodiment of the rich traditions and ocean-side lifestyles that define the area.

From our perspective, of course, deciding what is or isn’t historic is beside the point: Instead, we enter into these projects knowing that they are very important to a great many people and that, in a society that tends to tear down its past without blinking, we’re privileged to do our level best to make certain these properties will be there for future generations to enjoy.

The Annenberg Community Beach Club

This project is arguably among the most historic of all possible swimming pool/property restoration projects: As noted in passing above, the site was designed by Julia Morgan, the architect of Hearst Castle and a singular presence in the annals of California architecture.

During the 1920s, Hearst commissioned Morgan to design and oversee construction of a second home about 200 miles to the south of his famous castle – this one on the beach in Santa Monica and intended for use by Hearst’s long-time mistress, Marion Davies, who was also one of the leading movie stars of the era.

As was the case with Hearst Castle, the Davies residence, as it was originally known, became a gathering place for celebrities and the social elites of the day. After her death, the estate changed hands several times. The main house was torn down in 1956, leaving behind a smaller guest house, the swimming pool and some other structures.

Using a $28 million grant from the Annenberg Foundation, the City of Santa Monica started in the early 1990s to reinvent the property as both an historic site and a recreation facility. We became involved in 1997, at first compiling a feasibility study on the restoration of the pool as well as on updating the equipment so the pool could safely be opened to the public.

I covered the early stages of the project in WaterShapes’ June 2006 issue (“Restoring Waters Past,” page 60). At that time, the planning for the pool’s renovation had been completed and work on site was just beginning.

ARTFUL RECOVERY

To recap the story briefly, the place was in terrible shape when we arrived. The surviving structures and pool had long ago been abandoned, and it was all the city could do to keep squatters at bay. For safety’s sake, the pool had been covered with a temporary, low-profile wooden roof, and the entire property stood out as something of a missing link on what is otherwise one of the busiest, most upscale beachfronts in the United States.

The issues related to refurbishing the overall site go well beyond the scope of this article, but there are several points about the pool’s renovation that bear discussion.

First some credits: The senior project manager overseeing all aspects of construction and restoration was Rick Stupin of Charles Panko Builders Ltd. (Pasadena, Calif.). Frederick Fisher & Partners (Los Angeles) acted as project architects, while Mia Lehrer & Associates (also of Los Angeles) served as the landscape architect. Vaneelya Simmons was the project manager for the City of Santa Monica.

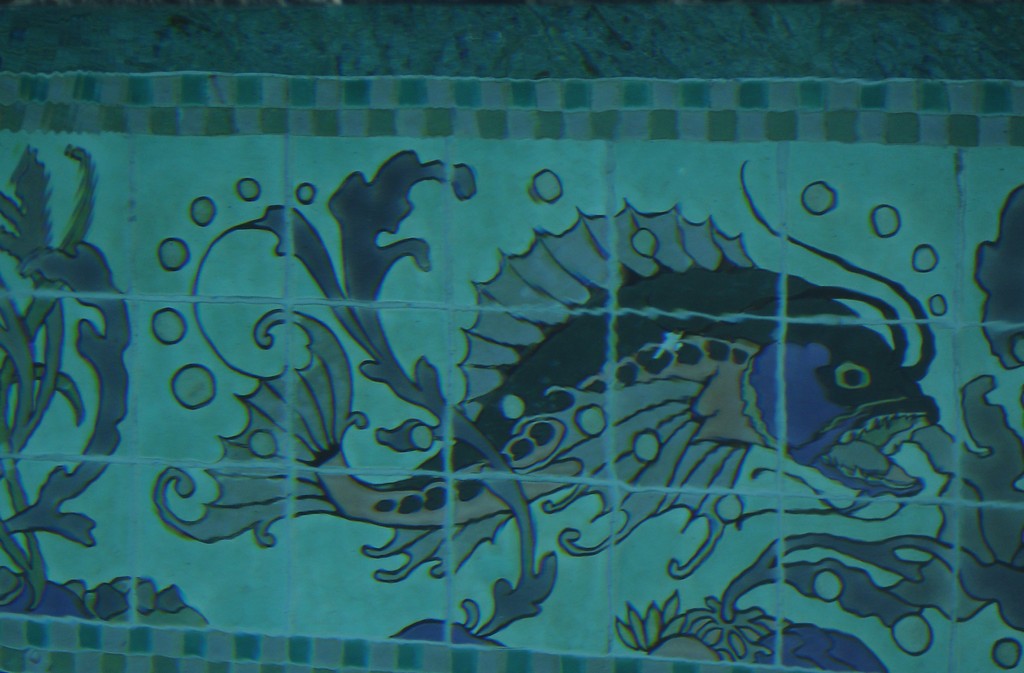

| The tile border and details within the pool are wonderful – a true testimonial to the artisanship that went into preparing a home for one of Hollywood’s biggest stars and witness to the fact that William Randolph Hearst and his architect, Julia Morgan, didn’t hesitate when it came to lavish details. |

Construction work on the pool was performed by Condor, Inc. (El Monte, Calif.) and expertly managed by company owner Fred Weiss. The patience, determination and flexibility he and his crews showed throughout the project was both remarkable and suitably relentless.

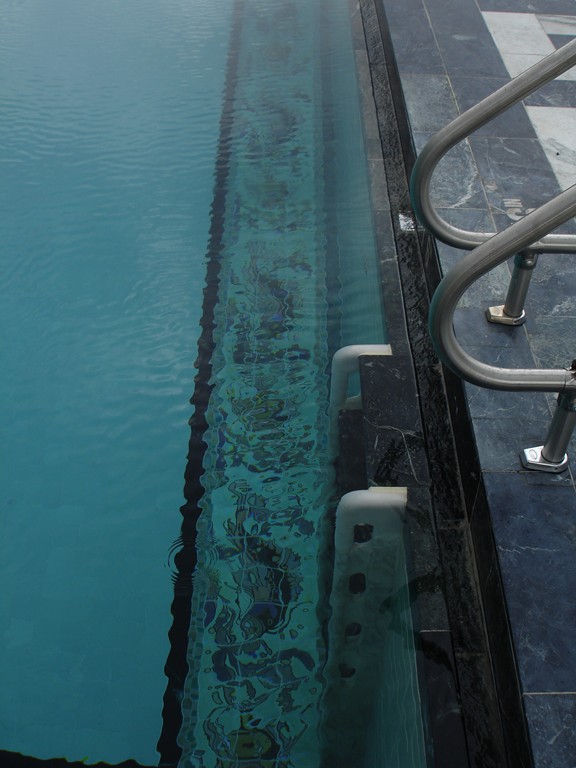

Now to the pool, which is 103 feet long and 22 feet, one inch wide – an odd set of dimensions to say the least, and it’s anyone’s guess why Morgan designed it that way. Although the watershape is not as elaborate as either of the pools at Hearst Castle, it had many similar features, including an all-tile finish with beautiful mosaics along with gutters, coping and handrails in beautiful marble.

The pool deck is also outstanding. The surface was covered in concrete inset with panels of marble tile laid out in a diamond pattern. The concrete portions of the deck were broken up and removed, but every piece of the marble tile was removed and catalogued to indicate its exact placement and orientation to facilitate eventual restoration of the original appearance.

The removal of the deck dramatically facilitated work on the pool, allowing us to excavate the outside of the shell and install new plumbing runs before the soil was re-compacted to support the refurbished deck.

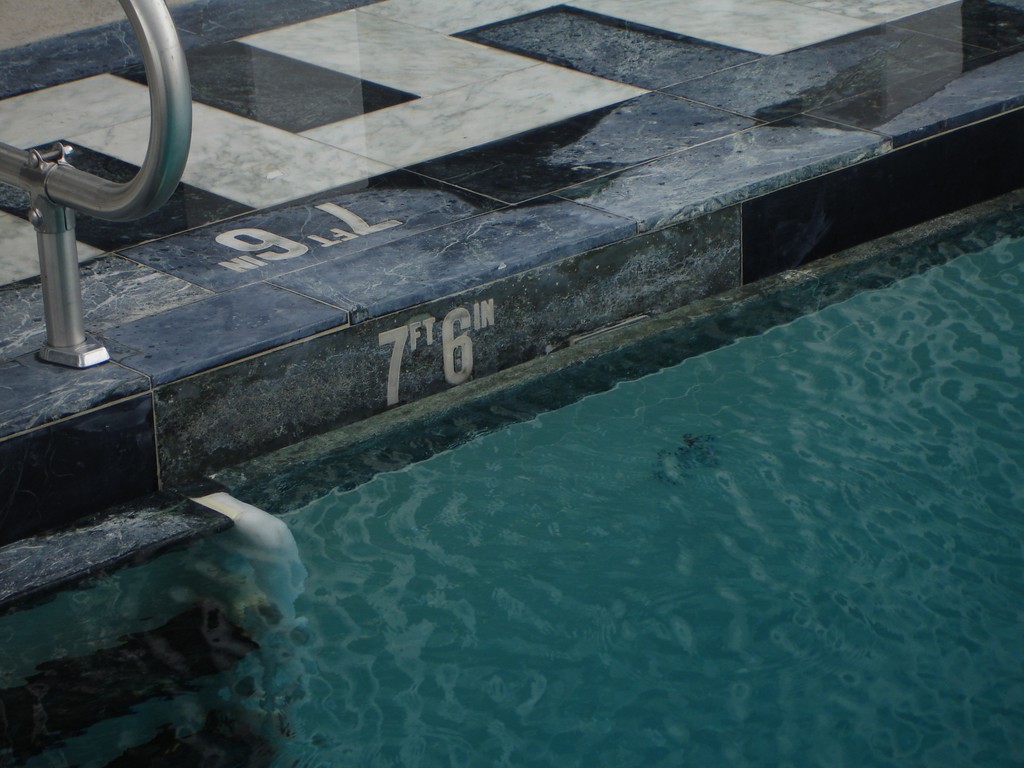

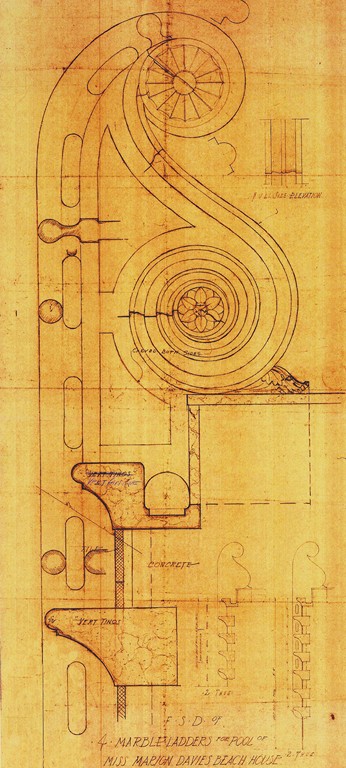

| The marble-inlaid decking, the marble gutter-and-coping system and the marble ladders inside the pool are all straight restorations of details Julia Morgan designed and installed. There was, however, one great loss: Although we had the stone and her drawings to work with, there was no way we could make the scrolled-marble handrails work in this commercial setting. |

As part of this process, Weiss and his crews discovered that, during original construction, the builders had backfilled the shell will all manner of debris – chunks of concrete, pieces of steel and more. In addition, while installing new light and plumbing fixtures (we kept these new penetrations to a minimum for obvious reasons), Weiss’s masons learned the hard way about the strength and density of aged, 24-inch-thick, poured-in-place concrete structures that had been reinforced with the square rebar that was in common use in the 1920s.

Before the decks were re-installed, each of the marble insets had been water-honed: While this didn’t affect the appearance, it had the benefit of creating a slip-resistant surface.

That small-seeming detail was only one of the several places where the local Health Department needed to mediate between its standards and the original pool design. Indeed, inspectors were involved from the start and were tremendously cooperative when it came to bending in cases where the historic pool’s configuration gave them pause. The shallow-end depth, for example, was an inch shy of four feet, making it fully five inches too deep. To accommodate this issue, they had us add an extra set of ladders and rails in the shallow end.

STEP BY STEP

Another issue to be negotiated had to do with the color of the pool finish and Health Departments’ usual insistence on white and nothing but white.

As we found it, the pool had beautiful ceramic tile mosaics throughout as well as a light-green field tile on the bottom. Recognizing the historic nature of the watershape and the fact that the tile was its defining feature, officials didn’t hesitate to grant a variance. Happily, the mosaics had survived years of neglect in very good shape, needing little more than cleaning and re-grouting. As a result of spalling, however, we had to replace all of the field tiles, using the same type of ceramic tile in an exact color match.

Around the edges of the pool, the gutter was a solid green marble that matched the decorative marble coping. Many of the gutter pieces and some of the coping had been damaged and needed to be replaced.

| Given the historic nature of the project, the city was unusually willing to grant variances that let us preserve the pool’s original features and appearance. So the tile borders stayed, as did the pale-green field tile, and we were also able to develop depth markers that seem at least consistent with the level of craft that went into the pool’s original construction. Officials even allowed us a variance on the depth of the pool, requiring us only to add a couple of ladders (with, unfortunately, plastic steps) in the shallow end. |

Happily once again, the project team was able to find the Vermont quarry that had originally supplied Morgan with her marble, and we were able to generate exact replicas of the original pieces. Not only was it the same quarry, but also the same vein from which the original material had been removed: You can tell the difference between new and old, but the distinctions are quite subtle even now and won’t be much of an issue at all once the new stone has weathered a bit.

Maintaining the theme of authenticity, we used brass drain grates in the gutters that are remarkably similar to what was found in the original pool. And in one of my all-time favorite compromises with health officials, where we had to place depth markers, we used water-cut marble inlays instead of the usual garish tiles.

As the issue of the depth markers highlights, the Annenberg Community Beach Club watershape was basically a nice residential pool that was being repurposed and redesigned for public use, meaning that beyond the often-subtle aesthetic restoration we were pursuing, we also had to update the watershape with a circulation system fully up to commercial standards.

The pool holds 105,000 gallons, operates with a 4.4-hour turnover rate and has been licensed to handle 113 bathers. To make it all work, the system includes a 10-horsepower pump (Paco Pumps, Brookshire, Texas) and a 27-square-foot, high-rate Stark sand filter (Paragon Aquatics, LaGrangeville, N.Y.). The water is chemically treated with sodium hypochlorite, with pH control courtesy of dual carbon-dioxide/muriatic-acid injectors.

The project earned a LEED silver designation, an extraordinary feat for a restoration of this nature. The energy-conscious system includes a solar heating array provided by Solar Unlimited (Cedar City, Utah) and installed under the guidance of company president Bob Dominguez. The pool also earned additional points for the efficiency of its pumps and gas heaters.

The facility’s grand opening took place on April 25, 2009 – a dozen years after we first became involved – and the public was welcomed to a new community center that not only includes the refurbished guest house and pool, but also several recreation spaces including beach-volleyball courts, picnic areas, a splash pad and ample parking.

Now that the pool is finished, we’re all excited to think that visitors will be swimming in a watershape designed by one of the most prominent architects in our nation’s history and will all get to enjoy a taste of the refined lifestyle that made Hearst and his properties so famous.

The Ennis House

In some cases, restoration work on historic properties requires a light touch.

That was just the case for us in 2008, when we were asked to participate in the renovation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles. The structure, completed in 1924, features an elaborate, Mayan-inspired, molded-concrete façade; some 15 years later, Wright came back to expand the outdoor areas and add a simple, elegant pool.

The house has long been a southern California landmark but was badly damaged by an earthquake in 1994 before being further harmed by torrential rains in the winter of 2004-2005. After this second blow, the house was condemned and for a time was considered as one of the most threatened of all historic sites in the United States.

The effort to save the Ennis House (also known as the Ennis-Brown House in recognition of a later owner) has been impressive: A dedicated foundation raised more than $15 million to cover restoration work, about $4 million of which was set aside to cover rehabilitation of the patio, deck and pool.

| Our role in restoring the pool at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House was small, but there are many stresses associated with working around and within architectural treasures as you walk the line between sticking to original intent while making certain all systems are fully functional and effective. |

In the grand scheme of things, our role was about as low-key as it gets: We were engaged as consultants to oversee the acid-washing of the pool and the careful cleaning and restoration of the pool’s coping and tile details. There was also a bit of housekeeping involved in upgrading some plumbing and equipment, but as such projects go, this one was about as non-invasive as it gets.

To be sure, our contribution to the overall project was significant despite its apparent ease, but you never know when you get into processes of this kind exactly how things will go. As a watershape restoration, this was quite straightforward; even so, there’s a remarkable measure of pride we take in saying we helped preserve a Frank Lloyd Wright house for future generations.

Palos Verdes Beach & Athletic Club

This project began for me as a simple matter of participating in my local community. The Palos Verdes Beach & Athletic Club had been established in 1930 and for decades had provided me and other longtime residents of the Palos Verdes peninsula with a beautiful venue for exercising and socializing – and for swimming right next to the ocean.

By the late 1980s, however, the property had been through many hands and had been closed for about ten years. The club’s beautiful Spanish Colonial-style building was in complete disrepair, its only occupants some pigeons and perhaps a coyote or two. But the situation began to look up in 1988, when the city decided to redevelop the site. I became involved soon after and was asked to redesign and update the swimming pool and the spaces around it.

The original pool was a rectangle 105 feet long and 45 feet wide. Its poured-in-place concrete shell was intact but had moved out of level, which wasn’t too surprising given its placement in the sandstone material that forms the cliffs atop which the club is located.

We did a geotechnical survey and discovered that the original shell had indeed experienced differential settlement. Given access issues and the size and strength of the existing structure, we knew demolition would be both difficult and costly and started looking for other solutions.

IN WITH THE NEW

The answer we came up with was simply to leave the original shell in place and install two new pools inside it – one a 75-foot lap pool, the other a small, general-purpose wading pool.

There had been about six inches of differential settlement through the years, enough movement to let us know we had to reinforce the foundation. We accomplished this by punching holes in the floor of the original shell and sinking piles down to bedrock – six in the wading pool and 45 within the lap pool. These piles are tied to a structural slab at intervals of eight feet or less.

| These two pools were installed several years back inside the shell of the club’s original, 1930s-vintage pool. Now it was time to add a large spa to an elevated deck overlooking the pools and the ocean beyond. |

We also removed the bond beam from the original shell, installing 15-pound felt as a bond breaker before forming and preparing the two new pools inside the existing structure. The new pools were completely supported on the system of piles, leaving the existing shell to continue settling independent of the new structures inside it.

We wanted to maintain a four-and-a-half-foot depth in the lap pool, which we knew would be a practical impossibility given the original pool’s configuration. To make things easier, we went with a perimeter-overflow system that raised the waterline while leaving the decks at their original elevation and the pool at the desired depth. (These depth issues didn’t apply with the shallower wading pool, so it has a standard coping/skimmer detail.)

All of this work was completed by 1992, at which point the club reopened and the watershape was named the Rossler Pool in honor of former mayor Fred Rossler, who had been instrumental in initial establishment of the club.

| The nautilus-shaped spa greets club members as they pass down to the pool level. The seat created by the twist in the ‘shell’ has already become a popular spot for watching the waves and taking in spectacular sunsets. |

From the start, the club’s managers had wanted a spa to go along with the new pools, but the original redevelopment budget couldn’t handle the extra expense. Planning ahead, we installed the plumbing runs we anticipated would be required by such a spa – a bit of forethought that would relieve future contractors of the need to tear up the decks. We came back in shortly thereafter and installed a circular spa adjacent to the lap pool, picking up those plumbing runs.

Two years ago, the club decided to add a second, more spectacular spa overlooking the entire pool area. Wanting to do something special, our firm designed a raised spa with a unique nautilus shape, filling the available space with an 18-by-10-foot vessel set atop its own pile system. The spa’s unusual shape and bench configurations establish a unique central lounging area overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Behind the vessel is a tile mosaic featuring peacocks.

Although it’s a brand-new addition to the club, it certainly harmonizes with the facility’s long history of celebrating its oceanfront setting and makes us proud that we’ve taken part in preparing the facility for its future.

William N.Rowley, PhD, is founder of Rowley International, an aquatic consulting, design and engineering firm based in Palos Verdes Estates, Calif. One of the world’s leading designers of large commercial and competition pools, his most notable projects include partial designs for the competition pools used in the Olympic Games in Munich (1968) and Montreal (1972), and he acted as aquatic consultant for the design of the Olympic Pool Complex in Los Angeles (1984). His projects also have included a wide range of noncompetition pools, including the White House pool in Washington, the Navy Basic Underwater Demolition Training Tank in Coronado, Calif., and the resort pool at the Hyatt Regency at Kaanapali Beach on Maui. Rowley is involved in a range of local, state and federal entities, consulting on construction and safety-code requirements. He is also a fellow of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers as well as the recipient of The Joseph McCloskey Prize for Outstanding Achievement in the Art & Craft of Watershaping.