Where Streams Live

As I see it, there are six main types of watershapes: pools, spas, fountains, ponds, waterfalls and streams. Although there is tremendous variety within each category, I think most of us in the business would put pools, spas and fountains in one sub-group and ponds, waterfalls, and streams in another.

Obviously, there’s room for overlapping here – waterfalls installed with pools, for example, or fountains in the middle of ponds. The key distinction for me, however, is the closeness with which a pond, waterfall or stream must imitate nature when compared to many pools, spas and fountains that need only suggest a natural design – if they need to do so at all.

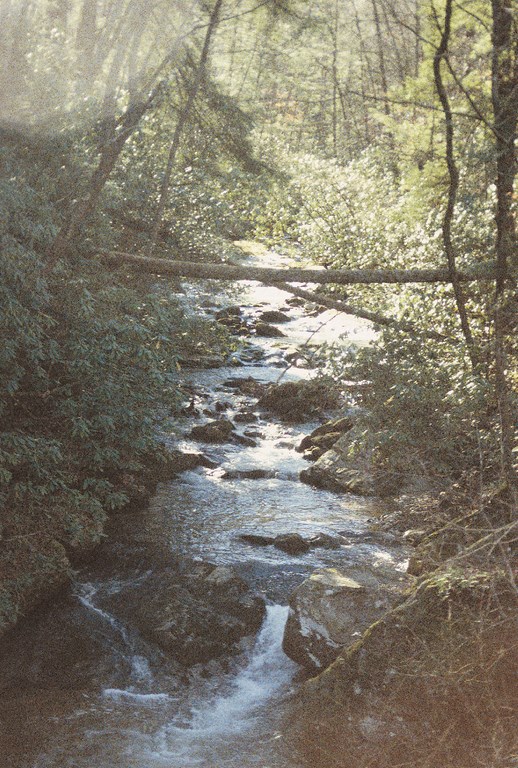

Hands down, it’s hardest to get “natural” right when it comes to streams. The difficulty isn’t so much with the construction techniques they require or even with their hydraulic design (both of which can get complicated). Instead, it’s the level to which the designer and contractor must first understand the way water interacts with rock and landscape in the natural world and then carefully mimic those effects in a fabricated watershape.

To see what I mean, let’s take a photographic tour of streams where they live, look at some specific areas, and then isolate some ideas we can apply to the watershapes we build.

GOING WITH THE FLOW

As with many watershape designs, success or failure with a stream largely boils down to how you treat the edges. Stream banks are especially difficult, because you need to create a natural-looking edge while making certain the structure holds water, that the water stays somewhat clear and that it all looks natural. Think about it: How do you create a bank that seamlessly rolls down into the water along with a stream that naturally meanders through and pushes at the edges of the space it occupies?

The answer is simple: You need to study streams as they exist in nature. Understanding how nature works will inform and shape every aspect of the work you do. In fact, I’d say that studying streams in nature is the key factor in your ability to imitate or re-create a natural look in your projects.

| One of my favorite effects occurs where water is diverted in two directions and thereby creates different points of interest in the same scene. In this shot, I also marvel at the way the bank stones lean down into the stream and serve to frame and anchor the composition of bank and stream both physically and visually. When I apply these concepts to my own work, I’ll think about setting this sort of stream up with both sunny and shady areas. The shade will give me the opportunity right away to set up some moss, which will soften the edges, enhance the natural impression and add to the visual interest created by large stones emerging from the stream. |

Consider the underlying structure of your watershape: Whether vinyl, EPDM or concrete, you set the channel or path that determines how a stream moves, flows and creates its own space. In nature, geology and topography determine the way a stream shapes itself, dictating where the turns are, how much and how far the water drops and the rapidity with which the water flows.

A designer/builder can define this underlying structure through his or her design or, in some cases, work with the underlying structure at the job site – perhaps a rock outcropping or a stone mass you can use to your advantage. If you’ve forgotten your geology (or never had it in the first place), pick up a book and take a look: Fault lines, protrusions, upheavals, glacial till and other features all can be used to define an underlying structure that will “sell” the natural qualities of your watershape.

The structure may be man-made, but the form created should be natural.

| When I came upon this stream, what impressed me most was the way the bank just seemed to flow right down into the stream as a magical, seamless intersection. In my opinion, this melding of stream and banks is the hardest effect to achieve in a man-made stream, and I must say I’ve seen some otherwise good, natural-looking streams seriously compromised by poor edges. In this sense, edges separate the good pro from the great pro: The key, I think, is to keep your liner or structure angling up ever so slightly instead of making a quick fold at a 90-degree angle. |

When a stream builder pays little or no attention to the way geology works, the project is almost always going to look unnatural. By contrast, when the builder looks at what makes a real stream turn, twist, spill or cascade and sees what happens with sand bars and dry areas, a great watershape may be in the making. The result will be a stream that reflects the way the natural world works.

This boils down to a couple of key questions I’m always asking myself: What are the major natural features that make up a stream? Why does it turn this way or that? What makes it shallow here, or deep? When a stream turns, what features are mainly responsible for the change in direction? After the stream does turn, what happens downstream? Again, the idea here is to force yourself to consider underlying structures.

These are the thought processes any good stream builder will pursue in starting to design and fabricate a stream. They keep you focused on cause and effect, and they enable you to begin working on streams that really have something to say – streams that look as though they belong instead of being little more than a trench bordered with rock that has no business being there.

WATER AT WORK

Once you have a channel and course in mind, you have to factor in the water itself.

Consider a stream project that involves lots of stone. In nature, this suggests a younger stream, a high degree of violence and tumbling rock – all associated with a steeper and stronger push of the water. Further downstream, you’ll find a collection of tumbled boulders and rock carried by the runoff from the spring thaw.

| The most impressive part of this scene is the way the larger stones change the course of the stream. This embodies my point about the specific geology that underlies a living stream; it also emphasizes the point that mixtures of small and large stones can be used to create a rhythmic interest in the stream. Note also the water-worn stones in the midst of the stream while stones with sharper edges lie just beyond the main flow of water. |

Now think about a setting in which a stream has cut its way along the same course, year after year, and has, through those years, eroded its own pathway. There may be lots of water involved here over time, but the scene suggests a gradual process rather than one of violence.

This issue of appropriate water flow is crucial to good design. You can work with volume in any number of ways to achieve effective results. The important thing to bear in mind is that water flow should tie in directly to the underlying structure you have created; that is, the flow must be appropriate to the channel. In this context, you must pay close attention to stone you place outside the stream itself: They are a major part of the design because it is these stones that tell the story of the stream.

| This stream shows perfectly how much interest is created when a natural stream separates into two distinct falls. The sound arising from these structures is amazing: Instead of a single sheet of water breaking that flat little run of water, a split cascade allows for a unique and distinctive water music. |

Usually, stream builders work somewhere between deep, curving rivers and rushing mountain streams in our residential settings. This gives us the opportunity to take the best of this (and little pieces of that) to create the finest possible watershape.

So what must we do to create great streams, to create streams with seamless banks and a water flow that fits the context of the site? How do we gain the understanding of the underlying structures that lets us accomplish the right look in the right places? It’s easy: Go to the real thing and look at streams as they are in the natural environment. In other words, go where streams live!

NATURE’S OWN

The notion that we should look to nature and the sorts of locations shown in the accompanying photographs to guide our designs should come as no great revelation. What does come as a surprise to me, however, is the fact that so few watershapers use this strategy to best advantage. How much time do you really spend looking at natural waterfeatures? Even more important, how do you look at them?

I’ve always spent a lot of time outdoors. In fact, I even had a creek in my backyard and spent a lot of time in it as a kid, much to my mom’s chagrin. But that’s not what turned the corner for me as a designer and builder of watershapes and other designed outdoor spaces. Yes, I had an appreciation for the joys of nature and moving water, but I had no clue that there was order amid the chaos, that there were patterns. repeated elements and structures hidden in a seemingly fractured world.

| This view offers a great example of the way nature uses emergent stones to create interesting effects. In looking for ways to re-create this, I would focus on the relationships between the stones and their size ratios – and their spacing, a factor that must not be (but too often is) overlooked. As I look at this photo, I can’t help noticing the directional forces these stones reveal, almost as if the rock had an energy of its own that moved my eyes over the scene. Those of us who set a lot of stone understand this energy and use it as we place stones in the overall context of a watershape. To me, what these stones might say to a geologist is much less important than what they say to me as an artist. |

How did I find those almost magical and mystical elements? This is where two additional factors enter the scene – factors that completely transformed my professional life: a camera and a sketchbook. If you learn to use them, these two tools will change the way you look, study, sense and, most important, interact with the natural world.

A camera forces you to slow down, really study the site and look at the composition of a scene. It pushes you to find the best angles, the best light, the best moods – and probably a hundred other things I still don’t appreciate on a conscious level but that come through on one level or another in the photographs I take.

| Here, I worked to create a valley stream – under some difficult topographic conditions: The stream was more than 45 feet long but dropped only 17 inches along that length! The key to achieving a natural effect in this case had to do with completely hiding the source of the water. |

A sketchbook does something entirely different: It makes you a participant in the scene, not just an observer. With a sketchbook, you can record what is around you in words and graphics, capturing the essence of a place. When you use a sketchbook – and I mean really use a sketchbook like a field journal – I promise it will have a profound effect on the way you look at, live in and interact with the natural world.

As you take pictures and make sketches, break the stream into sections and ask: “What can I take away from this section?” or “What can I take away from this scene?” Make yourself look at the overall setting through which the stream runs its course and consciously notice whether it is rough and tumbling or slow and shallow. Observe whether it’s full of large rocks and debris or deep and wide with long winding curves – and whether it’s loud and splashing or tranquil and calm. Now look to see what it is that makes or muffles those sounds.

What you’re doing here is putting the stream at hand into one of two broad, helpful categories: the mountain stream vs. the valley stream.

HAPPY MEDIUMS

This distinction between mountain and valley streams is useful in your field studies not so much because you’ll end up re-creating one or the other but rather because it gives you a complete design vocabulary. These themes and ideas let you conjure streams that exist somewhere between the extremes that have the characteristics of both – a section with a little tumbling action, say, along with a calmer portion with a little vegetation growing right down into the stream.

As you’ll see in the photographs, I’m constantly on the lookout for small mountain streams that run anywhere from six inches to six or seven feet wide and feature whole series of cascading waterfalls and pools of water. I carefully observe the small stone outcroppings I find along their banks, make note of the positions of trees close to the banks – and observe what happens where trees have fallen down into the water. I’ve also included two photos here to show the specific ways I apply some of what I’ve learned in the field to my own work.

| In this project. I worked to create my own mountain stream in miniature, starting with a hard, splashing cascade leading into a gorge and creating a flow of water fast enough that it seems to be cutting its way through the stone. The ferns and moss brought right up next to (and into) the stream add to the overall “mountain” impression. |

As I go, I look for pockets of vegetation down along the stream bank and photograph and/or sketch the ones that would be the most challenging and rewarding to re-create. I spot trees that seem to grow right out of a rock, hanging by the narrowest threads to life – yet are thriving and doing well. I look where the moss is growing and file all of these scenes away for use in setting up my own mountain streams.

I can’t say strongly enough how important it is for watershapers to get out in the field, study the physical world we’re being asked to re-create and really look at, listen to and feel what is out there. Go sit with a stream. The rewards are priceless – and this sort of immersion in the ways of natural phenomena is, I think, the key to becoming the best designers and builders we can be if that’s what we’re truly after.

And who’s to complain if taking a little nature hike becomes part of a good day’s work?

Rick Anderson is owner of Ston Wurks, a landscape-design firm in Columbia, S.C. A designer and artist with 21 years of professional experience, Anderson’s work focuses on the use of natural materials, particularly stone, in naturalistic settings. He is the founder of The Whispering Crane Institute, a landscape design “think tank” dedicated to exploring our physical, emotional and spiritual relationships with the land. The institute annually stages a Philo-sophy of Design Symposium in Hocking Hills, Ohio. Anderson is a past director of the Association of Professional Landscape Designers and has contributed numerous articles to a variety of trade and consumer magazines.