Timeless Impressions

By William Hobbs & Wayne Pierce

By William Hobbs & Wayne Pierce

Most people know Maya Lin for her bold design of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, but watershapers in particular should become familiar with a range of her other works as well. For nearly 15 years, reports William Hobbs, his company has been involved in producing intricate water effects for the famous artist, whose works draw fascinating connections between observers and the mysteries of time and nature.

The marriage of water and art can be extremely powerful and evocative, especially in the hands of a great designer. One who has taken the use of water to sublime and fantastic levels is Maya Lin, the artist who rose to prominence as a graduate student with her design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

At Hobbs Architectural Fountains, we have been privileged to participate in bringing Maya’s aquatic visions to life. Those works have often been ambitious and innovative and have required us to be just as ambitious and innovative in developing ways of moving water that bring her ideas to life.

Our partnership of design and technology in the creation of monuments and public works of art began more than a decade ago. The projects shown here display just some of our collaboration through those years.

WEAVING EXPERIENCES

Whether they include water or not, the works of Maya Lin are seldom simple in concept or theme. Rather, she sets up layers of motifs and meanings that are often drawn from nature as well as human history. Quite often, they’re touched by an acute sense of time, the passage of time and the indeterminacy of occurrences in nature and history.

Let me illustrate that sense with her most famous work, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, where she presents the names of those who lost their lives in the conflict in chronological order of their deaths. Thus, the wall creates a narrative beginning in 1959 and ending in 1975, and the passage of time is represented specifically by the horrific loss of human life suffered during the war.

In this way, a permanent structure, anchored firmly in the earth, captures a fleeting progression of events that are still affecting lives to this day.

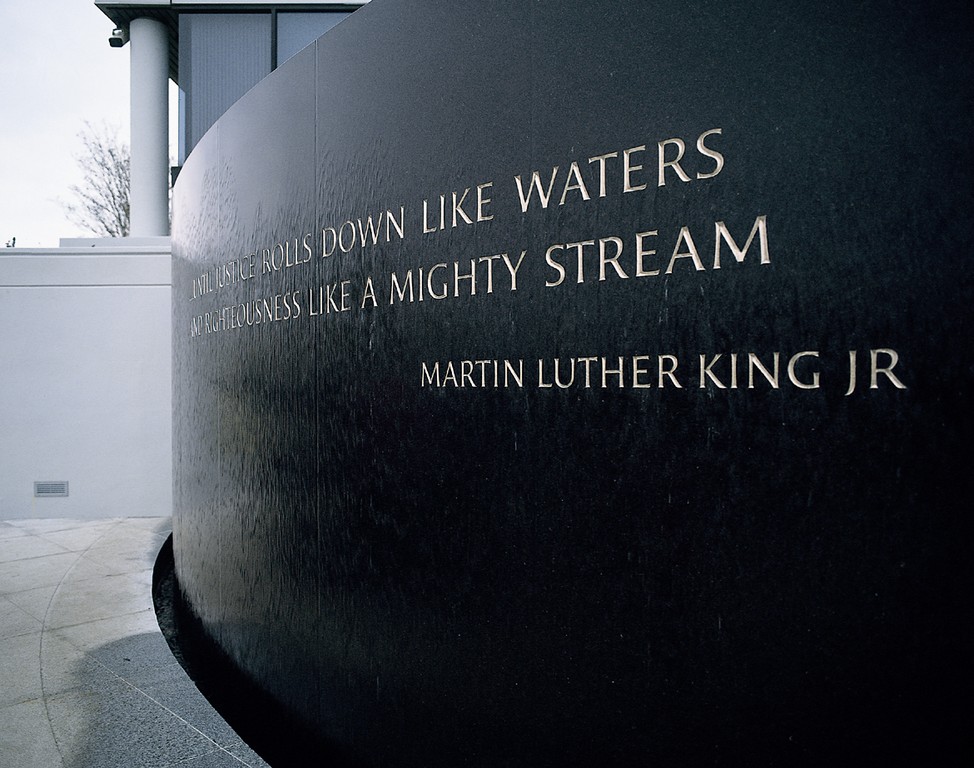

As similar effect is achieved with her Civil Rights Memorial, which strings together the events from the landmark court case of Brown vs. Board of Education in 1958 to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968while defining a crucial span in the history of race relations in this country.

In many of her other works, the sense of the moment is less tied to such specific historical time frames and becomes more evocative of the random procession of events within nature itself. Consider, for example, the cycles of freezing and thawing that lend profundity to the American Express Winter Garden depicted in this article – a distinct demarcation of time achieved through the physical presence of water.

In many cases, executing such ephemeral concepts has required an incredible degree of technical know-how and flexibility and creativity from us on the Atlanta-based staff of Hobbs Architectural Fountains. It is indeed rare and wonderful to participate in such projects, where water technology is used in service to such intellectually ambitious and distinctly artistic designs.

Civil Rights Memorial

Montgomery, Alabama

Maya Lin first contacted us about this project early in 1988, explaining that she wanted to create a wetted surface and generate an exact flow of the water for an artistic effect. Naturally, we were excited by the prospect of working with such a renowned designer, but we also were a bit concerned in this, our first project together, that what she envisioned might be difficult if not impossible to attain.

Working systematically, we set up a full-scale prototype. The first challenge had to do with the fact that the water table contained an offset core. When flooded, this offset created an uneven flow, and it took many iterations of cutting and staging the internals of the core as well as work on the table itself to generate smooth flowing waters over the entire surface.

The second challenge was setting up the flow so that the water achieved an acute reverse angle as it fell over the edge of the table. Maya wanted to see random droplets once the water had doubled back on itself. Through analysis and testing with the prototype, we found the texture we needed at the edge and the exact radial cut required to create the desired effect.

The second challenge was setting up the flow so that the water achieved an acute reverse angle as it fell over the edge of the table. Maya wanted to see random droplets once the water had doubled back on itself. Through analysis and testing with the prototype, we found the texture we needed at the edge and the exact radial cut required to create the desired effect.

Then we had to deal with the inscription on the wall behind the table and how to make water flow where Maya wanted it to flow – a surprisingly difficult engineering challenge. Obviously, carving letters into stone creates irregularities for water to flow over, so the voids had to be filled with a compound that reduced the disruption. From there, we decided how to handle the flow of the water into the narrow basin – and the whole project came together beautifully.

American Express Winter Garden

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Initially, this project seemed to be little more than a kind of glass water wall we’d executed several times before, but as Maya moved forward with her description, we soon recognized that this was to be something entirely new and unique.

Her concept was to generate a water wall approximately 25 feet high and 40 feet wide that would freeze in the winter – a wall, she told us, that also was to be integrated into the building. Inside, she set up a rolling, hill-like effect in the floor itself, flanked by an L-shaped pool. She wanted sound from the water, but no motion that might disrupt reflections, which we achieved by creating a “disturbance” under the rolling-hill floor that generated sound that reverberated off the walls but caused little or no movement as it moved into the reflecting pool. The pool itself was set both inside and outside the wall and seemed to be one vessel. In reality, however, there were two separate systems.

Outside, Maya wanted the waters to flow majestically down the glass when the temperatures were above freezing – and create various patterns of ice on the glass when temperatures dropped. This was no small challenge: The water wall was two sided, after all, and one side was part of a heated space. On the outside, moreover, we had to control the level and thickness of ice formation as a safety and structural issue.

Outside, Maya wanted the waters to flow majestically down the glass when the temperatures were above freezing – and create various patterns of ice on the glass when temperatures dropped. This was no small challenge: The water wall was two sided, after all, and one side was part of a heated space. On the outside, moreover, we had to control the level and thickness of ice formation as a safety and structural issue.

The solution was an “ice breaker” system: Through a network of freeze sensors and temperature controls, two separate pumping systems controlled the amount of ice on the wall and maintained fluid movement of water in the catch basin. The net effect: an impressive display of ice that constantly changes.

Principle Group Financial Headquarters

Des Moines, Iowa

Maya brought us in on this project, “A Shift in the Stream,” in 1996. Her concept was to create a glass wall on two levels of a three-story lobby that would feature small, narrow streams of water flowing down the glass with what she described tantalizingly as an “accidental quality.”

Our task was to generate those small flows of water in such a way that they would vary constantly in movement and direction as they flowed down the glass – and to do so intermittently. We achieved the latter by using solenoid valves hidden in the lobby’s ceiling. This allowed us to use a programmable controller to generate various on and off times for the flows.

The random flows were harder to achieve, which led us to set up another full-size mock up in our Atlanta studio. Maya joined us in generating options and valving solutions for achieving the level of water manipulation and the various flows she wanted. We also took the opportunity to test the joints between the glass panels and eliminate any water leakage or any potential flow behind the glass that might damage the wall.

The random flows were harder to achieve, which led us to set up another full-size mock up in our Atlanta studio. Maya joined us in generating options and valving solutions for achieving the level of water manipulation and the various flows she wanted. We also took the opportunity to test the joints between the glass panels and eliminate any water leakage or any potential flow behind the glass that might damage the wall.

On location, the cascading water appears to enter the floor of the second level of the lobby and continue down to the first level, where there’s a 40-foot long fracture in the wall. This fracture shifts the flow of water from the vertical drop above to a horizontal flow below, where various elevations constantly move slightly up and down across the entire length of the feature. As you approach the wall, you can hear the subtle sound of water flowing.

The challenge here was putting moving water behind the wall, with the attendant potential for damage to the wall over a period of time. After much discussion and several reviews, we created a trough system that minimized the risks.

Monroe Center

Grand Rapids, Michigan

The fountains for the Monroe Center, which Maya has dubbed “Ecliptic,” consist of two separate outdoor display systems and became a reality in 2000. The first is a circular granite disc set above grade. Water flows over about half its surface before falling off a knife-edge – a signature feature in many of Maya’s watershapes and something with which we were familiar.

In this case, however, the treatment was different: Typically, we’d flooded these features from the center and allowed the water to project outward in all directions. In this instance, we were flooding the disc from one side and needed the water to flow evenly across the surface.

Clearly, the stone had to be perfectly even to achieve this effect. Beyond that, we needed to develop a small discharge trough for the edge of the circumference – something we could hide beneath a granite capstone along with a fiberoptic cable. As water is introduced to this trough, it fills very slowly and releases the water in a controlled, smooth manner into a notch cut on the edge of the stone.

Clearly, the stone had to be perfectly even to achieve this effect. Beyond that, we needed to develop a small discharge trough for the edge of the circumference – something we could hide beneath a granite capstone along with a fiberoptic cable. As water is introduced to this trough, it fills very slowly and releases the water in a controlled, smooth manner into a notch cut on the edge of the stone.

When turned on, the fiberoptics, which are also set in the narrow catch basin at the base of the feature, disperse a white, glowing light across the surface of the stone as well as its base, lending a serenity to the scene that couldn’t have been achieved with conventional directional lighting.

The second feature is at the opposite end of the complex – another raised circular fountain, but one that uses a fog system to create unique and constantly changing effects. When the fog is not in operation, all you see is serene reflections. When it’s on, anything from changes in the humidity levels to drafts bring variety to the watershape – with fiberoptics adding a warm, mysterious glow.

William Hobbs, principal of Hobbs Architectural Fountains’ design and engineering group, is known for bringing the beauty and motion of water to landmark projects around the world. A veteran participant in national and international architectural design teams, he consults with architects and designers and offers them innovative approaches to including water in their projects’ aesthetic goals. To further this mission, he oversees new-product design and is the author and holder of patents for equipment and spray effects in the architectural fountain industry. He has lectured at the Harvard School of Design and taught seminars for the Construction Specification Institute, the American Institute of Architects and other architectural and landscape groups on the subjects of architectural fountain design and engineering.